Sydney Curtain

David McDiarmid’s Sydney Curtain (referred to previously as My Sydney), 1978, is a celebration of both Sydney and synthetic plastics of the 1970s. The artwork contains numerous types of plastics which have all been exposed to the same environmental conditions for over 30 years. For an art conservator this provides a fascinating study of how plastics deteriorate over time.

The Gum leaves in Sydney Curtain were identified as being made from cellulose nitrate. Most plastics react to oxygen and light by becoming brittle and discolored. However with cellulose nitrate this reaction becomes a catalyst in itself for further reaction thus accelerating the process of deterioration. This type of decomposition is known as autocatalytic.

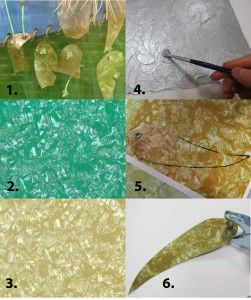

While two thirds of the leaves in Sydney Curtain were still in tact despite being brittle and discolored, one third had completely or partially broken away (1). We could, of course, simply display the artwork as it is, but the losses may be somewhat visually distracting and not a good representation of the artist’s intent. Alternatively we could replace some of the damaged and missing leaves so that the areas of loss do not become the focus when viewing the artwork.

The NGV is the custodian of an archive of McDiarmid’s unused collage materials, provided by the McDiarmid estate through its executor Dr. Sally Gray. Within the archive was a sample of cellulose nitrate that matched the reflective patterning in the leaves in Sydney Curtain. However, since the sample had been stored in an enclosed box, with minimal exposure to air and light, it retained its original bright green color, matching more closely the intense green seen in an early photograph of the artwork.

Given the significant difference in color intensity, using the original material to replace the losses would have produced a chromatic imbalance within the artwork. Nevertheless, the original material did provide a useful resource for producing a facsimile leaf that would blend in with the remaining leaves and still be noticeable as a non-original addition.

Recreating the Gum Leaves:

1. The original material from the archive was scanned and the digital file altered to match the colour of the aged leaves (2-3).

2. The digitally altered image was printed on to poly (ethylene terephthalate) PET film and the back of each sheet painted with an iridescent silver synthetic polymer paint to approximate the refractive character of the original material (4). Two sheets were then adhered together using archival (polyvinyl acetate) PVA glue to create the two sides of the leaf.

3. For broken leaves to be replaced the remaining upper sections were traced on to the prepared film, this gave a good indication of the original shape and size as the outer lines were continued downwards to form a natural point (5). The removed broken leaves were retained. For completely missing leaves whose presence is indicated by nylon treads protruding from the main poly (vinyl chloride) PVC sheeting, whole remaining leaves were copied and a balance in the composition was approximated.

4. A grommet was inserted at the top of each leaf and painted with gouache to color match the aged grommets still in place (6).

5. Original colored PVC cords were used to attach the leaves; where there was no cord, clear silicone tubing was used – this was colored to match the original ties by inserting a colored cotton thread through the tubing.

David McDiarmid is on display at NGV Australia until 31 Aug. Free entry.