BARK LADIES

ELEVEN ARTISTS FROM YIRRKALA

By Myles Russell-Cook

‘We want to bring knowledge of the past to the present to preserve it for future generations, and to understand what meaning it has in the present day and age.’

Dr Raymattja Marika AM, Inaugural Cultural Director of The Mulka Project

The complex symbolism that is present in nearly all Yolŋu art originates from iconographic and symbolic visual languages that have been passed down by Yolŋu people – the Traditional Owners of North-East Arnhem Land, Australia – for thousands of years. Art and art making is inherently important to all First Nations communities around the world. For First Nations people, art is often employed as a practical means of communicating complex cultural information.

The British arrived in Australia just over 230 years ago. The telling of art history in Australia often posits the arrival of Lieutenant James Cook in 1770 as the beginning of contact between Aboriginal people and the outside world. For Yolŋu people, however – from at least the eighteenth century and likely even earlier – there have been hundreds, if not thousands, of fishermen who sailed from Makassar on the island of Sulawesi (modern-day Indonesia) to trade with Yolŋu people. Yolŋu people also, on occasion, travelled to Indonesia and back again, formalising trade relationships. Understanding this unique history is central to understanding Yolŋu art, as it destabilises an otherwise Eurocentric reading of Indigenous art history, and instead centres Yolŋu people as active and intrepid explorers both within their art making, and within the world itself.

For over 65,000 years, Australia has been home to more than 600 different Aboriginal tribes. Within each of those communities are rich artistic histories and inherited visual languages, which have come to form the basis of contemporary Indigenous art today. Before 1970, no Yolŋu women painted sacred themes on bark or ḻarrakitj (memorial poles) in their own right. In recent decades, however, a number of women artists have taken to these media, becoming renowned both nationally and internationally for their daring and inventive works that challenge Yolŋu tradition and rewrite our understanding of contemporary bark painting.

Bark Ladies examines this as a watershed moment within the history of contemporary Indigenous art. All works in the exhibition are drawn from the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) permanent collection. Bark Ladies gives prominence to the work of eleven women who, each in their own way, have used their art to challenge our understandings and preconceptions about both contemporary and Indigenous art in Australia. Each of the artists included in the exhibition has, throughout her life, made work at Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre, or Buku, as it is known colloquially.

Buku is a Yolŋu community-run art centre in Yirrkala, located along the Gove Peninsula at the most north-easterly point of Australia’s Northern Territory. If you think of the Northern Territory as a rectangle, Darwin is in the top left corner, and approximately 700 kilometres to the east, in the top right corner, lies Yirrkala. The NGV has been actively acquiring important works on bark from artists at Yirrkala since Buku was founded in 1975; however, it is really only in the past two decades that the Gallery has turned its attention specifically towards the work of women.

Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka takes its name from Yolŋu Matha (the language of the Yolŋu people). In English, ‘Buku-Larrŋgay’ means ‘the feeling on your face as it is struck by the first rays of the sun’, while ‘Mulka’ means ‘a sacred but public ceremony’. Since its founding, Buku has been a meeting place and community hub for some of Australia’s most respected and prolific artists. The Bark Ladies exhibition is made up of over seventy works from the NGV Collection – a combination of single-sheet bark paintings, sculptural ḻarrakitj and installations – that span more than thirty years of painting.

Harvesting the bark sheets that are used for the paintings takes place during the wet season. Yolŋu men go out on Country and look for suitable trees, then, using hand axes, incise rectangular shapes into the outer layer of the tree. Working together, the men climb up high, often standing on the roof of the troopy (truck), and carefully remove single sheets of bark, which are taken back to the art centre. The rough outer bark is stripped off and the thin inner bark is weighted with stones and scorched with fire as a way of flattening it out. Once flat, the sheet of bark can be painted on.

As well as the painted sheets of bark, Bark Ladies includes a selection of ḻarrakitj. Yolŋu artists across Arnhem Land make ḻarrakitj by painting trees that have been hollowed out by termites. Ḻarrakitj were traditionally funerary objects, or ossuaries (bone containers), made from stringybark trees. Through the continuation of customary cultural practices, Yolŋu artists in Arnhem Land continue to assert their sovereignty over land and culture and create a tangible connection to their Ancestors. What were once intended for mourning ceremonies are now produced as a major contemporary art form.

It is customary for Yolŋu artists who paint Country and the stories it holds to use materials collected from Country. Various natural pigments, including gapan (also known as pipeclay/gypsum/chalk), ochre, sand and more, are mixed with both traditional and synthetic binders to create the paint. In recent times, some Yolŋu artists have begun working with discarded printer cartridges recycled from the rubbish tip, an innovation that opened up an array of technicolour pigments previously not available to Yolŋu artists.

The prelude to the main Bark Ladies exhibition is a new commission by Maŋgalili clanswoman of the Yirritja moiety, Naminapu Maymuru-White. Naminapu learned to paint from an early age, taught by her father and uncle, Narritjin and Nânyin Maymuru, who were both well-known artists.

Naminapu was born in 1952 and began painting as an assistant to her father and uncle, using miny’tji, or sacred clan designs.1Miny’tji is a style of sacred painting in which linear markings are used to represent important cultural information.

Recently, Naminapu has shifted her practice, removing all references to the miny’tji and instead concentrating on her own original and innovative ways of representing her clan and her identity. She is known today for her immediately recognisable and intricate use of black and white ochre. Naminapu’s paintings are highly labour intensive. She uses a skewer stick and marwat (human-hair paintbrush) to map out stars and galaxies in graphic black and white ochre. Naminapu’s main subject is the Yolŋu concept of Milŋiyawuy, or as it is known in English, the Milky Way. For the NGV exhibition, Naminapu has produced six ḻarrakitj, each titled Milŋiyawuy, and also worked with the Gallery’s in-house designers to create a vinyl floor-based work titled Riŋgitjmi gapu, 2021.

Riŋgitjmi gapu as a concept roughly translates to ‘river of Heaven and Earth’. For Naminapu, the temporal Milŋiyawuy River and the astral Milky Way are one and the same. The artwork Riŋgitjmi gapu is an immersive depiction of the night sky that audiences are encouraged to walk across. Through the work, the artist shifts the audience’s perspective by inverting sky, sea and land, turning the bluestone floor into a conceptual and spiritual river of stars. As she explains,

There was a Maŋgalili family, a Maḏarrpa family, living somewhere near Cape Shield, and there were two men that decided to go hunting in a canoe. They paddled and paddled and paddled until they got to the horizon, where they ran into a big wave. The wave tossed the canoe, and they were underwater. They were trying to get up back to the surface, but they couldn’t. They refused offers to be helped, as they prefer to die in the sea. Their spirits went up, and they were travelling through this river of stars. There was a lot of stars, which represent all the people that have gone before. And they were joining them to go through that river of stars called Milŋiyawuy in my language. And they happily lived up in the sky, to join with the others. These designs I have been doing like this focus back to the land, the people, and song, because they are all related. Through songs, through rivers, through people.2Naminapu Maymuru-White, interview with author, 2021.

After viewing Naminapu’s floor work, audiences enter the exhibition proper, which is divided into three distinct spaces. Naminapu’s ḻarrakitj are presented at the entrance to the first space. Each pole offers a unique composition of the Ancestral night sky. Notably, one pole, visible at the front of the installation, depicts two Ancestral figures, Munuminya and Yikawaŋa, who are seen travelling across the night sky in a canoe. This moment of figuration is unusual for Naminapu; it interrupts her proliferation of black and white markings to further reinforce the connection between water and the starry sky.

Continuing further into the exhibition, audiences move through different sections, which are dedicated to different artists. Rather than delineating themselves clearly, these spaces reveal overlapping and shared themes of identity, Country, spirituality, time and the universe. For Yolŋu these are also concepts that bleed into one another. The doors between each space remain open, meaning that from a visitor experience point of view, there is no one entrance to Bark Ladies.

The space closest to Naminapu’s floor is dedicated to work by five of the Yunupiŋu sisters – Nancy Gaymala, Gulumbu, Barrupu, Ms N Yunupiŋu and Eunice Djerrkŋu – who are all at the forefront of Yolŋu art. The very first work in this space, and the earliest bark painting by a woman in the NGV Collection, is a single painting from 1990 by Nancy Gaymala Yunupiŋu that represents the ancestral being Bäru – the crocodile. Gaymala was an established bark painter as well as a master weaver, printmaker, carver and painter of wooden sculptures. Gaymala, who was the daughter of Muŋgurrawuy and sister to Galarrwuy and Mandawuy Yunupiŋu, began painting in the 1990s and is acknowledged to be the first Yolŋu woman to have a solo exhibition at a commercial gallery, held in 1992.

For Yolŋu people, Bäru is a profoundly important Ancestral being. Central to many Ancestral stories, Bäru is the carrier of gurtha (fire) and is connected to a special and powerful story belonging to the Gumatj and Maḏarrpa people. Gumatj man and leader in the Yolŋu community, Galarrwuy Yunupiŋu AM, described Bäru as a flame of fire through which comes energy and power – strength.3Galarrwuy Yunupiŋu, ‘Tradition, truth & tomorrow’, The Monthly, Dec. 2008, <www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2008/december/1268179150/galarrwuy-yunupingu/tradition-truth-tomorrow#mtr>, accessed 23 July 2021.

It is understood by Gumatj people that in Ancestral times, the leaders of Yirritja moiety clans harnessed the powers of fire for the first time as part of a ceremony at Ŋalarrwuy on Gumatj Country. Fire was originally brought to the Gumatj people by the Ancestral crocodile, and then spread across ceremonial grounds, transforming animals into sacred totems. The Ancestral crocodile man who created gurtha in Maḏarrpa Country threw a log into the flames that then spread through the dry bush. In doing so, he was so badly burnt that he then slid into the sea, where he transformed into a crocodile and stayed there forever.

Because of this, fire is closely associated with Bäru and is represented by Gumatj artists as a diamond pattern. Early bark paintings by Yolŋu men that depict fire and Bäru often show the diamond pattern as ordered and tight. There is a conventional formality to the men’s painting that is not present in Gaymala’s work. Gaymala’s work foreshadows a departure from the usual way that Yolŋu artists paint, in that there is a freedom, spontaneity and sense of gesture in her style. Gaymala’s career as an artist was tragically cut short when she died in 2005. She was recognised as an Elder among her siblings, so it was not until her passing that her sisters – Gulumbu, Barrupu, Ms N Yunupiŋu and most recently Djerrkŋu – followed in her footsteps.

Gaymala’s younger sister, Gulumbu Yunupiŋu, was the first Yolŋu woman to gain significant acclaim for her bark paintings. Gulumbu is now also known as the Star Lady. During her life, Gulumbu garnered international acclaim for her work. In 2004 she won the First Prize at the 21st National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Awards (NATSIAA) for her work Garak, the universe, 2008 (Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney). Like Gaymala, Star Lady began her career as an artist by watching their father, Muŋgurrawuy, paint.

Gulumbu’s paintings depict gan’yu (the stars) and Garak (the universe). A great source of inspiration for Gulumbu’s practice were stories told to her by Muŋgurrawuy who would share Ancestral histories about the creation of the Yolŋu universe. As an emerging painter, Gulumbu primarily assisted her father with his paintings, and it was not until more than thirty years after his death that she began working as an artist in her own right.

Her fascination with stars and the universe led her to develop a signature style – a dense network of crosses unified by fields of dots. Each cross represents a star, and all that is visible within the known universe. The dots that sit behind and in between the crosses represent everything that isn’t seen, something Yolŋu people refer to as ‘the second stars’. In reading Gulumbu’s work, we are presented with a universe that is full. There is no negative space, and everything is connected. During her life, Gulumbu spoke about how if you could see everything that exists, then the night sky would be nothing but stars. The variations in colour, tonality, density and scale create an opportunity for contemplative meditation; each individual painting operates as a window into infinity. As she states, ‘This is how we tell our stories. Not with decoration. Not in pretty pictures. Just like this’.

The current coordinator of the Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre, Will Stubbs, knew Gulumbu well. Following her death, he wrote an obituary to Star Lady that appeared in the magazine Artlink in June 2013. Stubbs, who is bilingual and has lived much of his life in Yirrkala, wrote about how for Yolŋu, life force inevitably matures into ‘non-corporeality as a natural stage of growth’, and how in death, the souls of some Yolŋu people, such as the Maŋgalili, live forever in the Milŋiyawuy River.

In the obituary, Stubbs noted that after Gulumbu won the National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award, he followed her around as she spoke to the various journalists, writers and academics, who all wanted to discuss the stars. When being interviewed, Gulumbu kept stressing, ‘look up to the stars, just as trees grow up, people sit or stand up’. In his tribute, Stubbs recounts he was struggling to grasp the significance of the word ‘up’ for the artist, but then realised she was referring to the direction of growth. As he recalls,

The reason that the Westerners weren’t hearing her was that in our language she was saying: ‘When you grow up you are going to be dead’. In fact she was saying that what we call death, and think of as a full stop, is actually a growth stage. When I asked her if this was what she meant, she smiled.4Will Stubbs, ‘Gulumbu Yunupiŋu (1943–2012)’, Artlink, June 2013, <www.artlink.com.au/articles/3971/gulumbu-yunupingu-281943E28093201229/>, accessed 23 July 2021.

There is a direct correlation between Star Lady’s paintings of the universe and the work of her younger sister, Barrupu Yunupiŋu, also known as the Fire Lady. Barrupu’s depictions of gurtha are closely connected with the creation of the Yolŋu universe. What we glimpse in the gestural diamond designs that sit behind Bäru in the work by Gaymala is brought to the fore through the work of Barrupu.

Barrupu’s work pulsates with the intensity of Ancestral flame. Before she began painting on bark, Barrupu worked on paper, and these early works offered clues to the unique and impulsive energy that has since come to define her oeuvre. Judith Ryan AM, former NGV senior curator of Indigenous art, wrote about Barrupu’s singular way of painting flame, smoke and ash, describing how Barrupu would use horizontal and vertical lines of different intensities, which crossed each other asymmetrically, in order to accentuate her compositions:

The red flames, the white smoke and ash, and the black charcoal pulsate through the bark, paralleling the spread of ancestral fire from Ŋalarrwuy to other sacred sites implicated in this narrative. Barrupu shows the fire in close-up, stressing its paramount importance to the Gumatj people. The Gumatj language, Dhuwalandja, is itself the tongue of flame, which incinerates dishonesty, leaving only the bones of truth.5Judith Ryan, ‘Barrupu Yunupiŋu Gurtha (Ancestral fire)’, Art Journal 56, 20 Dec. 2018, <www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/barrupu-yunupingu-gurtha-ancestral-fire/>, accessed 23 July 2021.

The selection of paintings by Barrupu in Bark Ladies chart her short but impactful career. Her earliest works alternate between horizontal and vertical axes, with the diamonds interlocking to create an almost three-dimensional effect, while her later works are characterised by their stark vertical planes. Together, Star Lady and Fire Lady redefined what Yolŋu art could be, by telling Ancestral stories in an utterly contemporary and original way.

While Gaymala, Gulumbu and Barrupu painted Ancestral stories, stars, and fire, younger sister Ms N Yunupiŋu pushed Yolŋu art even further still. Ms N Yunupiŋu passed away in later 2021, and so talking about her is still difficult. She will always be, without question, one of Australia’s boldest contemporary artists. Her work came to be characterised by an absence of customary meaning. Her earliest paintings were small in scale and filled with figuration. She would paint formless images of unspecified creatures resembling geckos, turtles, crocodiles and more. When Ms N Yunupiŋu was a young woman, she was gored by a buffalo in a wild apple orchard, and traces of the terrifying experience can still be felt through her work. Early paintings show her figurative use of circles to represent apples, and in her later work, those same circles morphed into abstract meditations on rhythm and tone, no longer symbolic of anything at all.

Throughout the years, Ms N Yunupiŋu’s work continued to evolve, increasing in scale and visual complexity. In 2009, Ms N Yunupiŋu removed all figurative components in her work, so that only the crosshatching remained. Her style is intense, filled with nuance, depth and rhythm. It was often (lovingly) referred to in Yolŋu Matha as mayilimiriw, which literally translates to ‘meaningless’.6Franchesca Cubillo, ‘Nyapanyapa Yunupiŋu’, National Gallery of Australia, Australian Government, <https://nga.gov.au/exhibition/undisclosed/default.cfm?MnuID=ARTISTS&GALID=34475&viewID=3>, accessed 23 July 2021. She expressed an obsessive preoccupation with painting through the freeness of her brushstrokes. When I am in the presence of her work, I am drawn to it as a sort of contemplative void. It reveals as much about us, the viewer, as it does about the artist. Will Stubbs once described it as being like a form of spontaneous Zen. Today Ms N Yunupiŋu paints almost solely for the joy of painting.

My father Munggurrawuy Yunupiŋu taught me how to paint. I learnt from watching him. He was always working. He said to me, ‘When I am gone you will follow behind me and paint too. Show the people – paint and work’. That is what he said, and that’s what I do.7ibid.

Featuring in Bark Ladies, and on display for the first time since its acquisition by the NGV, is Ms N Yunupiŋu’s immense work Gäna (Self), produced between 2009 and 2018.

Gäna is a hypnotic installation made up of sixteen irregularly shaped bark paintings and nine ḻarrakitj. The individual elements that make up the installation vary: some are highly stylised and minimal, while others are more decorative and busier. As an artist, Ms N Yunupiŋu shifts effortlessly between dense and minimal forms, for the most part arranging her compositions around shapes and lines. Gäna embodies Nyapanyapa’s intuitive style. As a collection of work, it can be read as a self-portrait, through which we sense the artist’s hand and body in every mark. In contrast to the artist’s small stature, the work itself is big and bold. Nyapanyapa takes abstracted forms, lines and circles, and reworks them into large-scale, frenetic and impulsive patterns.

Audiences gain a true sense of Ms N Yunupiŋu’s trajectory as an artist by viewing Gäna alongside other works by the artist in the NGV Collection, including the NGV’s earliest painting by her, Wild apple orchard, 2008. We also can see Nyapanyapa’s sophisticated use of the bark itself, and its materiality, in Pink diptych, 2015, which is made up of two single sheets of bark that abut each other so as to create the illusion of a continued surface.

Alongside the works by Ms N Yunupiŋu are three recent acquisitions by the latest Yunupiŋu sibling to take to painting, Eunice Djerrkŋu Yunupiŋu.

In April 2021, Djerrkŋu debuted her work as a painter in Melbourne with a sellout solo exhibition. Djerrkŋu, who is the widow of community leader Roy Marika, was born on Inglis Island in East Arnhem Land in 1945. Her paintings are unusual. She works on both bark and timber board to tell the story of her conception as a spiritual mermaid. Her work stems from a fantastical memory of herself as a mermaid who spent her days sunning herself on a rock in the sea. The story goes that while in utero, Djerrkŋu’s father accidentally speared her (back when she was a fish) leaving her with a scar on her right leg. She tells the story of her painting, saying:

My dad sees the tail of the mermaid and thinks he has seen a fish, so he walks closer and closer and closer and silently puts the woomera into the spear ready to throw. He throws the spear at the mermaid, but she jumps into the water. The spear hits her tail though and the blood from it sits on the water. My father speared my spirit being, it shows here on my leg … this black marking. Speared me thinking I was a big fish; the fish dived deeper in a cave underneath the sea … and there was lots and lots of blood. My father felt sorry for that fish seeing lots of blood. He cupped a handful and smelt it and realised that it was human blood.

He dreams. In his dream he sees the mermaid and realises it was no ordinary fish. It was me. I was telling him in the dream, ‘That was me dad, don’t spear me. Bapa … why did you try to spear me? It is I, it was not a fish’.8‘Artwork certificate, Eunice Djerrkŋu Yunupiŋu’, Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre.

Mermaid tales appear in myths around the world, but the Yolŋu mermaid, which appears in both fresh water and salt water, is perhaps lesser known. Djerrkŋu’s paintings are rendered using a combination of natural earth pigments and reclaimed toner ink from discarded printer cartridges. She was not the first artist to paint with toner ink – that was Maḏarrpa artist Noŋgirrŋa Marawili, whose work can be seen in the other half of the exhibition.

The set-up of the galleries in which Bark Ladies is presented allows audiences the opportunity to enter the exhibition from either side, meaning that while there is one title wall and formal start to the show, there are multiple ways that audiences can encounter and experience the work. The first work those who enter Bark Ladies from the other direction will encounter is an installation by Dhuwarrwarr Marika.

Dhuwarrwarr Marika is a Rirratjiŋu Elder and the daughter of ceremonial leader, political activist and artist Mawalan Marika, who taught her to paint on bark. She is often regarded as the first Yolŋu woman to paint on bark in her own right. Dhuwarrwarr’s Birth of a nation, 2020, was included as a finalist in the 2020 National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Awards and is now in the NGV Collection. The designs in her work contain within them the identity of the coastal place known as Yalaŋbara, a location of the utmost importance to Dhuwa moiety people. Yalaŋbara is the fabled landing site of the Djaŋ’kawu Sisters, the major creator beings who arrived there from their mythical island Burralku. Birth of a nation comprises six large bark paintings and five ḻarrakitj, which bear the Rirratjiŋu miny’tji (design).

The designs on Dhuwarrwarr’s work are rendered in bold red, black and white ochres, and represent salt water drying off skin, as well as the sand sliding down the dunes while the Djaŋ’kawu Sisters climbed. Dhuwarrwarr’s work creates an optical illusion. The geometric shapes that wrap the barks and ḻarrakitj shift irregularly. She paints the trajectory of the Earth and all the Ancestral histories that are embedded within Country, transforming Rirratjiŋu stories into a mystifying three-dimensional installation.

After viewing Dhuwarrwarr’s work the audience travels down corridors where they will encounter the work of two prolific artists, known (among other things) for their work with unconventional colours. These are Maḏarrpa artist Noŋgirrŋa Marawili and Djapu artist Dhambit Munuŋgurr. In 2020 the NGV exhibited a major installation by Dhambit Munuŋgurr at the second NGV Triennial. The work consisted of fifteen bark paintings and nine ḻarrakitj, each painted in various tones of vivid acrylic blue paint. In 2005 Dhambit was badly injured in a car accident, leaving her with an acquired brain injury and significant physical disability. While it is customary for Yolŋu artists to paint with materials collected from Country, and while Yolŋu people are strong in their sense of protocol, they are also profoundly compassionate. And so, following her accident, Dhambit was given special permission to paint with store-bought paint, which did not require hand grinding. Until 2019, Dhambit used these acrylic paints to re-create tones of ochre (mainly orange, red and yellow), moving into bold blue and other colours only recently.

Despite being the dominant colour in the natural world that is visible to the human eye (the sky and the sea), blue is relatively rare in living nature, and even rarer as a naturally occurring pigment. When I first met Dhambit she was working from a paint palette made from an old piece of cardboard; on it she had written the words, ‘water blue, midnight blue, cobalt blue, ultramarine, Australian blue, and Australian sky blue’. These are the shades of blue that formed the basis of her installation. Dhambit’s work relates to her late mother’s Gumatj clan. Included in Bark Ladies are images painted with spontaneous energy that re-imagine the spiritual and physical properties of sacred totems, places and the Gumatj fire. In Dhambit’s case, these stories are transformed specifically through her use of blue.

The newest work by Dhambit in Bark Ladies, produced in 2021, is a portrait of former Australian prime minister Julia Gillard. This work represents a major shift for Dhambit, whose previous images were all drawn from Ancestral memories and traditional Yolŋu stories. Order, 2021, shows Julia Gillard standing in parliament, surrounded by limpfaced, unnamed, seated politicians. Yolŋu people appear in the bottom left of the composition, storming the parliament in ceremony dancing with spears.

Julia Gillard was scheduled to visit Yirrkala during her time as prime minister. In anticipation of her visit, Dhambit prepared a work in her honour; however, following a spill that ousted her as the leader of the Labor Party, the visit was cancelled. This important moment in Australian history has stayed with Dhambit, forming the inspiration for this new work. Gillard also became globally famous for a speech described simply as ‘the misogyny speech’, where she called out then opposition leader Tony Abbott and the political culture within Canberra for its treatment of women. Dhambit’s work commends aspects of Gillard’s legacy, while also critiquing the state of contemporary politics. Other works in this series that are not included in the exhibition show her son Gapanbulu Yunupiŋu playing the yiḏ aki (a Yolŋu musical instrument) in the parliament chamber, as well as Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg being pushed out to sea by a group of Yolŋu holding spears.

Presented alongside Dhambit’s work is a series of paintings by Noŋgirrŋa Marawili, one of Buku’s most senior artists, who is well represented in the NGV Collection. Noŋgirrŋa was born on the beach at Darrpirra, north of Cape Shield, in around 1939, and is a daughter of the Maḏarrpa leader Mundukul and a Gälpu woman, Buḻuŋguwuy. She is also a widow to Djapu leader Djutjadjutja Munuŋgurr, who himself won the Bark Painting Award at the National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Awards in 1997, for a painting on which Noŋgirrŋa assisted.

In late 2017, Noŋgirrŋa challenged what it meant to collect materials from Country when she became the first artist to start working with recycled printer cartridges. Noŋgirrŋa produced her first pink works as etchings, and carried that on to bark, mixing the printer toner with ochre to create a brilliant fuchsia colour. Following that, in early 2018, she returned to pink again, producing another suite of pink works on paper. Since then, with increasing scale and audacity, Noŋgirrŋa has introduced pinkish hues to multiple barks and most recently to ḻarrakitj.

For years Noŋgirrŋa has been at the forefront of Yolŋu art. In 2018 she had a solo retrospective exhibition, Noŋgirrŋa Marawili: From My Heart and Mind, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and was then included as a major artist in NIRIN, the 2020 Biennale of Sydney, curated by Brook Andrew. In 2015 Noŋgirrŋa produced one of the largest bark paintings ever made at Buku, Lightning in the rock, 2015, a work that represents Baratjala, the Maḏarrpa clan estate adjacent to Cape Shield. Baratjala is an important place for the Maḏarrpa clan, as it is where Mundukul the Lightning Snake lives far beneath the sea. Lightning in the rock is characteristic of Noŋgirrŋa’s more recent, theatrical style. Her work is often heightened by her use of negative space and has gradually developed over the years, with many of her early works characterised by their highly patterned surfaces. Bark Ladies features a small selection of works by Noŋgirrŋa from the NGV Collection.

As well as her monumental Lightning in the rock and spirited pink paintings is a new installation by the artist that represents Waṉḏawuy, the Djapu homeland of her late husband, Djutjadjutja. Waṉḏ awuy is the spiritual home for two Ancestral beings, Mäṉa the Shark, and Bol’ŋu the Thunderman. Noŋgirrŋa’s work is made up of eleven graphic black and white squares of bark painted with an elegant grid. The grid design refers to the landscape of Waṉḏawuy, a network of billabongs surrounded by ridges and high banks. The lines reference woven fish traps, which briefly restrained the powers of the Ancestral shark, while the squares refer to different states of fresh water, the source of the Djapu soul.

Along the walls nearby to Noŋgirrŋa’s and Dhambit’s work are two paintings by Naminapu Maymuru-White representing Milŋiyawuy, as well as four paintings from 2020 by senior Dhuḏi-Djapu artist Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda. In 2011 Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda produced a significant body of work, in collaboration with Australian painter John Wolseley.

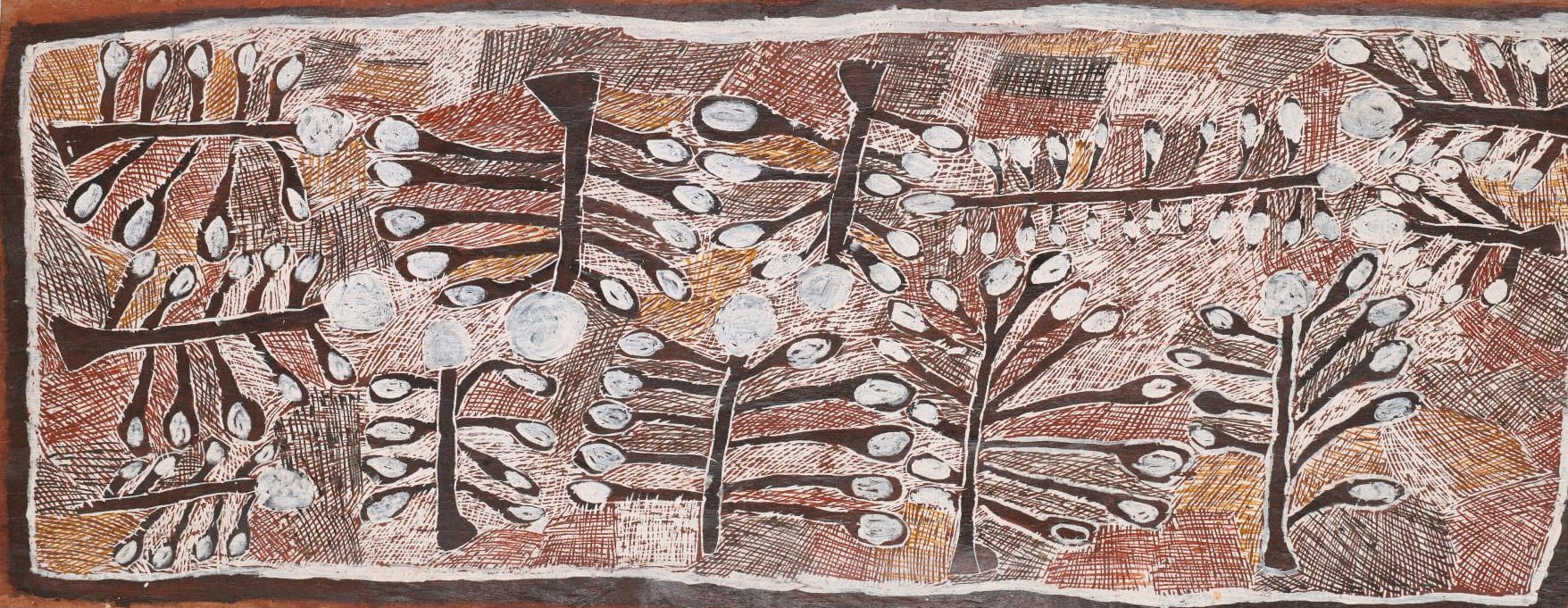

Wirrpanda’s work is rooted in her knowledge of edible plants and natural species found throughout her home in Arnhem Land. Bark Ladies exhibits two of Wirrpanda’s last bark paintings, made just before her passing in 2021, for her solo exhibition Guṉḏirr. These paintings by Mulkuṉ are stripped back and tight. She has removed all crosshatching so that the composition is highlighted by being placed within a sheet of negative space. The subject of Wirrpanda’s elegant and minimal compositions is guṉḏirr (magnetic termite mounds), which are home to munyukuluŋu (magnetic termites) and ŋäḏi (meat ants). Somewhat poignantly, ŋäḏi are a talisman of Mulkuṉ’s sacred identity and are associated with mourning ceremonies for the deceased. Her importance was recognised with her posthumous Works on Paper Award at the 2021 National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Awards.

Nestled within this gallery is a ‘cube within a cube’ – a mirrored room that echoes the significance of the Djapu grid design in the work of Noŋgirrŋa by placing a series of ḻarrakitj onto unconnected plinths, and using the mirrored walls to create an illusion of infinity. The ḻarrakitj in this ‘infinity room’ include pink Djapu designs by Noŋgirrŋa Marawili, a selection of blue poles by Dhambit Munuŋgurr and five previously unseen works by Malaluba Gumana.

During her life, Malaluba Gumana was known for making work on paper, glass, bark and ḻarrakitj. The five ḻarrakitj included in Bark Ladies are each titled Dhatam (Waterlilies), which refers to plants that grow at Garrimala, a billabong near Gängan, a sacred site for Malaluba’s mother clan, the Gälpu people. The twisting lines in white and green ochre reference Wititj (the olive python) and his companion Djaykung (the Javanese file snake). Wititj is an omnipotent Ancestral being, known in English as the rainbow serpent. The Gälpu clan miny’tji that appear within the leaves and forms of Malaluba’s Dhatam are sacred designs that allude to the power of lightning that exists within these beings.

In Ancestral times, the rainbow serpent travelled through the lands belonging to the Gälpu clan, and now these two sacred snakes live among the dhatam, causing ripples and djari (rainbows) on the surface of the water. When sunlight hits the scales of the snakes it forms a prism of light, making a rainbow. During storms, the power of lightning is understood to be the moment when snakes strike with their tongues, and thunder is understood to be the sound the snakes make as they move along the ground.

The images in the pages that follow are evidence of an artistic movement that both maintains and breaks free from customary tradition. The old attitudes that divided Western from Indigenous art dissolved long ago, and today Yolŋu art sits at the forefront of a global contemporary movement. And it is primarily women who have shaped this new way of working.

Whether it is an acrylic, bright blue crocodile painted by Dhambit Munuŋgurr; the gestural fuchsia and magenta ḻarrakitj painted by Noŋgirrŋa Marawili; or the kaleidoscopic illusional installation of Dhuwarrwarr Marika, Yolŋu women continue to reinvent what it means to be a contemporary artist in Australia. As the goalposts move further and further apart, both men and women at Buku continue to be inspired by these daring matriarchs, whose visionary way of seeing the world has changed art in Australia forever.

Acknowledgement

All information in this essay has been made available through the generosity of Yolŋu people. I wish to acknowledge in particular Naminapu Maymuru-White, Eunice Djerrkŋu Yunupiŋu and Dhambit Munuŋgurr for the conversations we had, and for their generosity and guidance. I also thank Yolŋu cultural advisors Ishmael Marika, Dela Munuŋgurr and Wukun Wanambi, and Will Stubbs and Judith Ryan AM for their assistance and original research. I have done my best to ensure that the information within this text is accurate; however, I acknowledge the fluid nature of cultural information and do not claim any authority over these stories.

Notes

Miny’tji is a style of sacred painting in which linear markings are used to represent important cultural information.

Naminapu Maymuru-White, interview with author, 2021.

Galarrwuy Yunupiŋu, ‘Tradition, truth & tomorrow’, The Monthly, Dec. 2008, <www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2008/december/1268179150/galarrwuy-yunupingu/tradition-truth-tomorrow#mtr>, accessed 23 July 2021.

Will Stubbs, ‘Gulumbu Yunupiŋu (1943–2012)’, Artlink, June 2013, <www.artlink.com.au/articles/3971/gulumbu-yunupingu-281943E28093201229/>, accessed 23 July 2021.

Judith Ryan, ‘Barrupu Yunupiŋu Gurtha (Ancestral fire)’, Art Journal 56, 20 Dec. 2018, <www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/barrupu-yunupingu-gurtha-ancestral-fire/>, accessed 23 July 2021.

Franchesca Cubillo, ‘Nyapanyapa Yunupiŋu’, National Gallery of Australia, Australian Government, <https://nga.gov.au/exhibition/undisclosed/default.cfm?MnuID=ARTISTS&GALID=34475&viewID=3>, accessed 23 July 2021.

ibid.

‘Artwork certificate, Eunice Djerrkŋu Yunupiŋu’, Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre.