Introduction

John Thallon was the leading frame maker for artists in Melbourne from the 1880s well into the twentieth century. Thallon’s ledger is a book of client orders and financial accounts used in the daily operation of the business for the period 1888/89–1903. It is a significant archival document providing unique insights into the world of art and picture framing in Melbourne during this period. Through the NGV Centre for Frame Research, the ledger has been both digitised and transcribed, providing researchers and the general public an unprecedented opportunity to access and search for information in this historic document.

John Thallon and his ledger

Emigrating from Scotland, John Thallon and his brother Thomas established a framing business in Melbourne in 1878. As well as being a trained craftsman, John was an artist, completing classes at the National Gallery School, and he continued to produce and exhibit his paintings as time allowed. Located in Melbourne’s artistic quarter at the Eastern end of Collins Street, the business soon attracted major commissions and a large clientele of artists. Like other framers of the period the business was not limited to frame making, providing a range of services including art packing and transport, the production of architectural and furniture items, frame and painting restoration, and the supply of artists materials. For more information about John Thallon and the framing business, see Framers in Focus: John Thallon

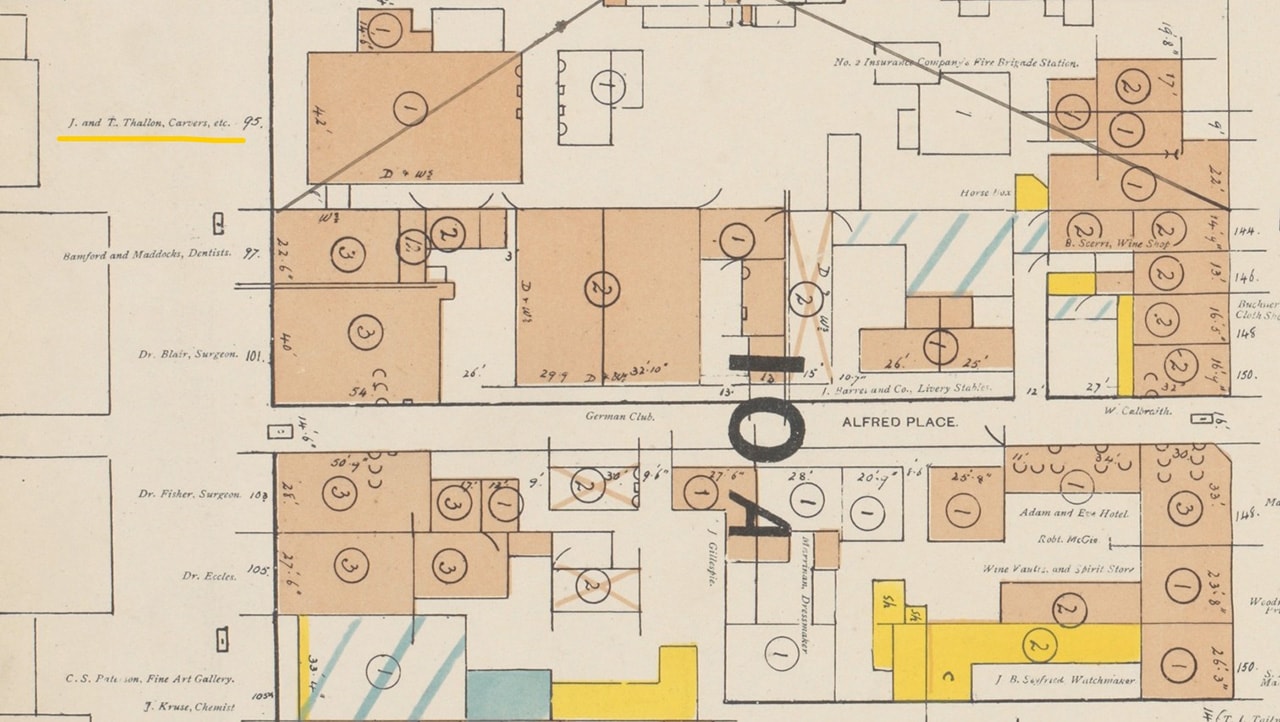

Detail of map showing Thallon’s premises (underlined in yellow) from Mahlstedt & Gee, Standard plans of the City of Melbourne, 1888, p.6. Collection of the State Library of Victoria, http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/126848 (accessed 28 August 2023).

The ledger is a historical primary source document detailing the activities of Melbourne’s leading framing business during a significant period of its operation, over fifteen years from October 1888 until April 1903. During this time the business had six different addresses in Collins Street, Little Collins Street, Russell Street and the Eastern Arcade (133 Bourke Street). The period the ledger covers includes significant events in the history of Melbourne and its artistic community, such as the boom period of the 1880s, the development of the Australian Impressionism movement, the Depression of the 1890’s and the formation of the first Australian Parliament with Federation in 1900.

As a research document the ledger can assist in further understanding Thallon’s business and clients. Areas of research include framing preferences of artists, art transport practices, and business operations such as connections with allied firms of furniture makers, architects and other frame makers. The ledger is among a rare group of archival material from historic frame makers that has been preserved. 1Within Australia another example is material from S.A. Parker at the Art Gallery of NSW, while in the UK the British picture framemakers, 1600–1950 on-line directory at the National Portrait Gallery in London, refers to framer’s business records where these are known. The existence of the ledger today is largely because the business started by J. & T. Thallon has continued to operate, with several different owners, up until the present day. The current owners are Jarman Framing, with the ledger amongst a collection of historic material owned by the firm that dates back to the time of John Thallon himself.

Description of the ledger

The ledger is a leather-bound book with handwritten details of the work to be undertaken for each client. The book has lined pages and is divided into alphabetical sections, with the long edges of the pages cut-out to create a series of tabs. Clients’ names appear as headings, with entries below. Entries may include multiple items, for example ‘8 frames for photos’, ‘cleaning and repairing 29 frames and pictures’. Some of the entries have an accompanying small, simple sketch of the frame to be made, recording the approximate profile (cross-section shape) of the frame. In most cases, each client order has been crossed out, presumably at the time the job was completed, or the account paid.

Generally, only the day and month are recorded in the first column of the ledger, however, a number of entries have the year noted in the main text, mostly in relation to the payment date. Using this information, the year of nearby entries is indicated. Sometime after the last entry in 1903, groups of pages in the first section of the book were glued together to create rigid supports on which a series of photographs and illustrations were mounted. These include black and white photographs of frames and furniture pieces and pages cut out from frame moulding and ornament catalogues.2One of the catalogue pages appears to bear the emblem of London frame maker Richard Scully, as reproduced in Jacob Simon, The art of the picture frame, National Portrait Gallery London, 1996, p.45. Unfortunately, this means that most entries for clients with names beginning A to F are unable to be accessed.

Thallon’s ledger opened at one of the letter ‘L’ pages, showing clients including Longstaff

Pages at the front of Thallon’s ledger covered with sections from the trade catalogue by Richard Scully, London

Transcription

Over the years Thallon’s ledger has been a valuable source of information for researchers of Melbourne’s frame history (see Further reading). In 1990 the NGV Conservation Department obtained a photocopy of the ledger. Through studying this document we have gained information about artist framing preferences, as well as identifying entries for specific frames in the NGV collection, such as Frederick McCubbin’s Winter evening (below), and Jane Sutherland’s Numb fingers working while the eye of morn is yet bedimmed with tears.

Frederick McCubbin, Winter evening, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, purchased, 1900. Winter evening retains its original Thallon frame

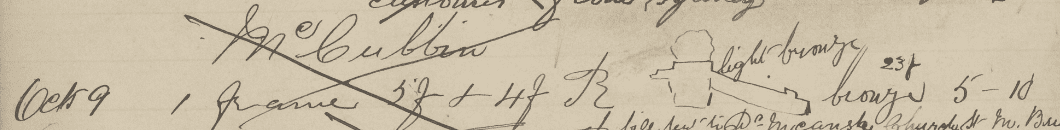

Thallon’s ledger entry for Frederick McCubbin’s Winter evening, as identified by date, size and profile sketch.

With the shutdown of the NGV in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, there was the opportunity to transcribe the information from the ledger into a database, opening a new dimension of research possibilities. Assistant Conservators Bella Lipson-Smith and Dominic King were tasked with transcribing the ledger into an Excel spreadsheet. They used a photocopied version of the ledger to decipher the sometimes hurriedly handwritten notes, including historical and abbreviated terms, and record them into the database. The database includes all the written information in the ledger, including frame dimensions. In total 2400 entries were transcribed, indicating the mammoth scale of the task. Please see A guide to using the transcription for further information.

In addition, each of the approximately 285 clients listed in the ledger have been researched using on-line sources and a summary written, with a focus on identifying clients who were artists. This information is accessed within the transcription, by clicking on a client’s name.

Analysis

The significant value of the ledger transcription is that it allows instant searching of the data, such as by client or framing term, providing users with the ability to easily undertake highly focused research about the Thallon business and its clients. After completion of the transcription and client summaries, a preliminary analysis of the overall information in the ledger was undertaken. Areas of focus were whether clients were artists/non-artists, or businesses (including institutions); the gender of clients; and whether clients purchased picture frames.

It is estimated that the 285 clients in the transcription represents around three-quarters of the total number of clients for the business for the period 1888-1903, given that the entries for clients with names A to E and most F’s were not able to be accessed.

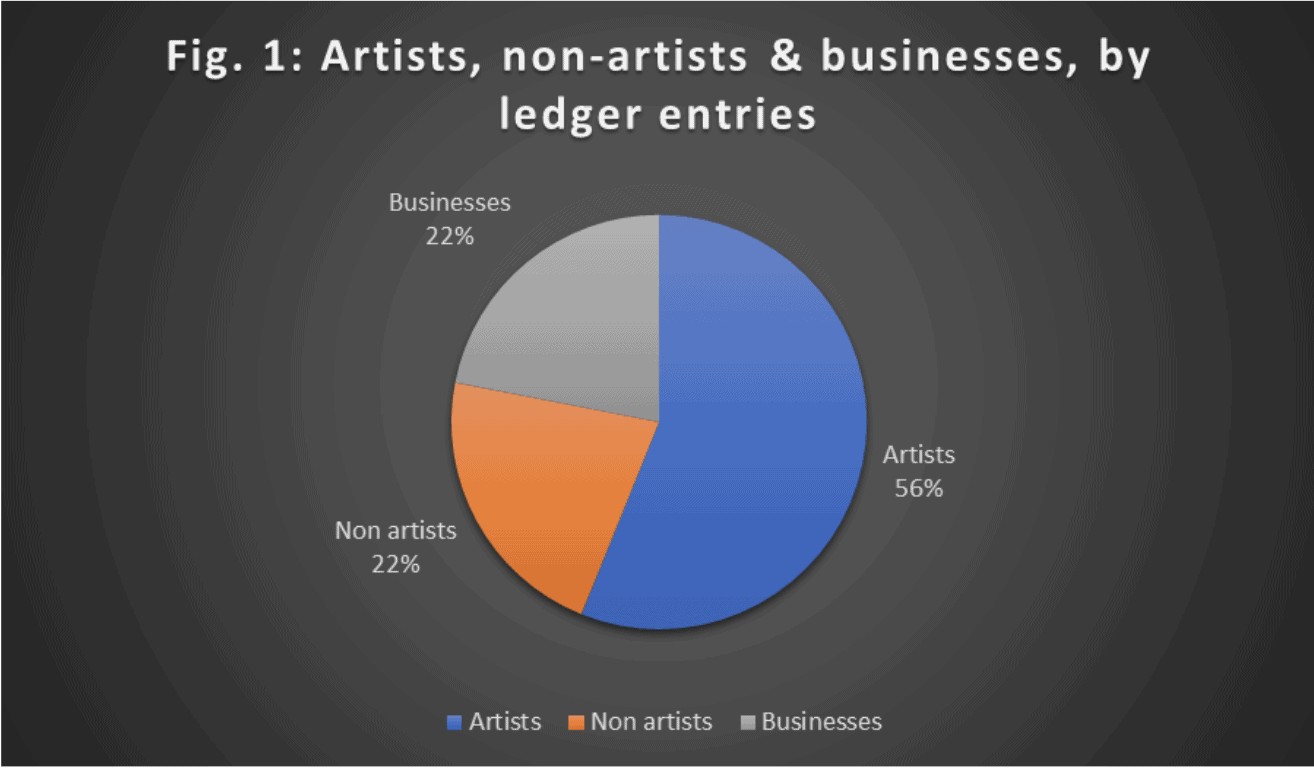

Artists were identified through research of available documents on-line, plus additional evidence provided by ledger entries indicating artwork being transported to/from studios. Therefore, this group mainly represents professional, exhibiting artists. Amateur artists, who pursued art as a hobby, were occasionally able to be identified, while there are likely to be unidentified amateur artists included in the ‘non-artist’ group. Of the 285 clients, around 31% were identified as artists, 51% non-artists, and 18% were business or institutional clients. However, when the actual number of ledger entries for each client was examined, over half the entries (56%) were for artists, suggesting that the majority of Thallon’s business was based on work for artists (Figure 1). Both the groups ‘non-artists’ and ‘businesses and institutions’ each comprised 22% of the entries.

(Figure 1). Artists, non-artists & businesses, by ledger entries.

When considering individual clients only (i.e. not businesses and institutions) it was seen that close to a third were female, over half male, and for the remainder the gender was unknown.3 Of the female clients close to half were artists, whereas for the male clients, a much smaller proportion, just over a quarter, were artists. However, when looking at the actual number of ledger entries, work done by Thallon for artists represent around three-quarters of the entries, for both the female and male groups of clients.

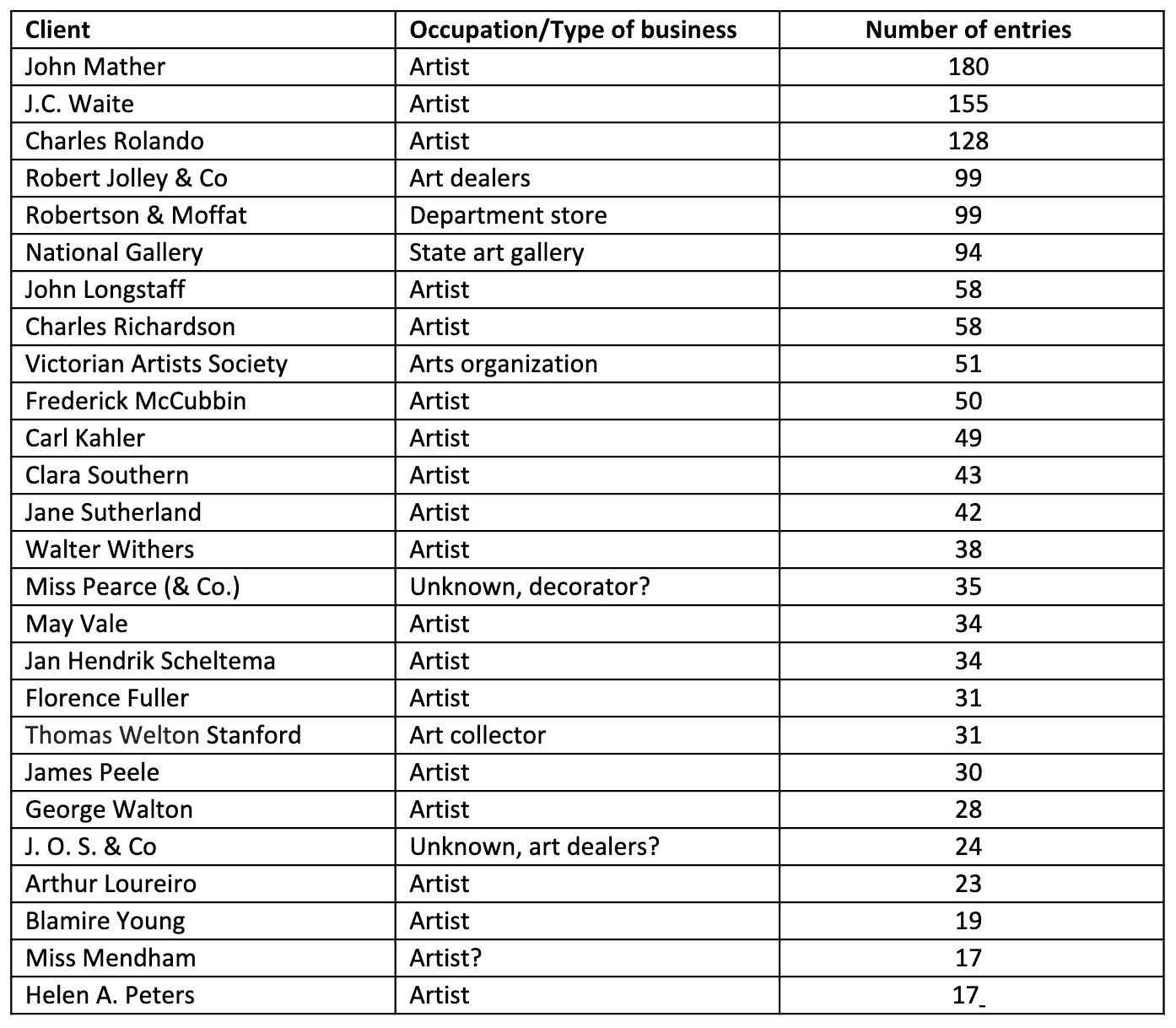

Table 1 (below) lists Thallon’s major clients (including businesses). Just three male artists account for almost 20% of the total number of entries (John Mather, J.C. Waite and Charles Rolando). This was followed by three business clients: art dealer Robert Jolley & Co, the department store Robertson & Moffat, and the National Gallery of Victoria, together representing 12% of the total entries. The female artists with the most entries were Clara Southern and Jane Sutherland.

Many artist clients used Thallon for frame making as well as art transport. Looking at the entire group of clients, over 64% included at least one frame order in their ledger entries, indicating that while Thallon offered a range of services, frame making was a primary aspect of the business.

Table 1: Thallon clients by number of ledger entries (top 25)

Conclusion

John Thallon’s business occupied a rare position in late 19th century Melbourne as preeminent framer to the city’s leading artists. This successful and dynamic business provided services to meet a strong demand with many regular clients, including working artists. In terms of picture frames, the business provided a range of frame styles and prices, with frames influenced by the latest European artistic trends.

Through the NGV Centre for Frame Research we are continuing to investigate styles of frames produced by the company and hope to find more clues about the numbered mouldings mentioned in the ledger. Considering the era in which the ledger was created, the transcription confirms that women clients were well represented and provides insights into their working practices. We hope that others find the digital transcription as valuable as we do and look forward to hearing about its use in researching a multitude of aspects about Thallon’s business, its clients, as well as broader historical studies.

Further reading:

Claire Newhouse, John Thallon 1848-1918′, Melbourne Journal of Technical Studies in Art: Frames, The University of Melbourne, 1999, pp.81-98.

Elizabeth Cant, ‘Inside the picture framing business: the ledgers of John Thallon, 19th century picture framer of Melbourne’, Australiana, May 2001, pp.39-43.

Dr Hilary Maddox, ‘Picture Framemakers in Melbourne c.1860-1930’, Melbourne Journal of Technical Studies in Art: Frames, The University of Melbourne, 1999, pp. 1-32.

John Payne, Framing the Nineteenth Century: Picture frames 1837-1935, The Images Publishing Group Pty Ltd., Mulgrave, Victoria, 2007.

Acknowledgments

This Centre for Frame Research project was made possible through the generous support of Professor AGL Shaw (AO) Bequest. Many thanks to Jarman Framing for providing permission for the NGV to digitise the ledger and present the digitisation with the transcription on-line.

In the Conservation Department, Bella Lipson-Smith and Dominic King are acknowledged for their dedicated and enthusiastic work in 2020 immersed in the world of the ledger and Thallon’s clients. Suzi Shaw is thanked for her ongoing assistance with many aspects of the project, as is Manon Mikolatis for her contributions. In addition, the following staff members are thanked for their work completing the research and writing client summaries: Caitlin Breare, Carl Villis, Jason King, Jessica Lehmann, Kate Douglas, Raye Collins and Raymonda Rajkowski.

In the NGV Multimedia team, Jonathan Luker is acknowledged for his technical expertise, passion for the project, and hard work to convert the Excel spreadsheet into the version that we see on-line. Thanks to Madi Reader and Jenny Walker for their behind the scenes work and making it look stunning. Thanks also to Predrag Cancar, NGV Photographic Services, for photographing the ledger.

Finally, many thanks to Michael Varcoe-Cocks, Associate Director Conservation and MaryJo Lelyveld, Conservation Manager, for their on-going support of this work.

Notes

Within Australia another example is material from S.A. Parker at the Art Gallery of NSW, while in the UK the British picture framemakers, 1600–1950 on-line directory at the National Portrait Gallery in London, refers to framers’ business records where these are known.

One of the catalogue pages appears to bear the emblem of London frame maker Richard Scully, as reproduced in Jacob Simon, The art of the picture frame, National Portrait Gallery London, 1996, p.45

For the purposes of the study, it was assumed the convention of the period was for women to be given the title of either Mrs, Miss or Mistress and men the title of Mr, Reverend or Captain. For regular clients, often just the surname was used. If a surname had no title and could not be linked to another client, then the gender was considered unknown.