In October 1972, Annette Dixon, the National Gallery of Victoria’s Curator of European and American Art After 1800, was brimming with excitement. At the age of thirty-four, she had steered the institution towards its biggest single acquisition using gallery admission funds. This was Jean Ipoustéguy’s Death of the father (La Mort du père), a 6-metre-long, multi-part marble, bronze and stainless-steel installation arranged to resemble the floorplan of a basilica. It presented a narrative of the physical decay of a clerically allegorised father figure, witnessed by the crouching form of a sculptor-son whose erect phallus manifests a tumescent sexual life force. ‘I have fallen in love with it,’ Dixon told a reporter from the Herald newspaper. ‘It has passion. It is sensual. It is erotic. It demands to be touched.’1John Hamilton, ‘Art? It was love at first sight’, The Herald, 25 Oct. 1972.

The acquisition of this enormous and commanding sculptural grouping had been negotiated for more than a year since Dixon first recommended it in early 1971. Ipoustéguy’s dealer, Claude Bernard Haim in Paris, had initially requested $85,000 for the work, which Dixon had seen photographs of in one of his catalogues. After Melbourne art dealer Georges Mora interceded on the NGV’s behalf, travelling to inspect Death of the father at Haim’s private residence, La Besnardière, in Villedômer near Tours in central France, the price was negotiated down to a still hefty $60,000. Dixon’s Submission for Purchase memorandum to the NGV’s Trustees in February 1972 stated: ‘This is undoubtedly the most significant work which Ipoustéguy has created to date and one of the greatest pieces of sculpture produced in the last decade’.2 Annette Dixon, Jean Ipoustéguy, Submission for Acquisition, 15 Feb. 1972. That the acquisition of Death of the father was not all smooth sailing would seem to be indicated by Dixon’s later admission that ‘[i]t took a lot of discussion – believe me, the acquisition was no light-hearted thing – and eventually the trustees agreed’.3 Hamilton. Even the letter of support that Melbourne sculptor Lenton Parr, then principal of the National Gallery of Victoria Art School, provided for Dixon’s acquisition was couched in ambivalent terms. Noting that the work ‘would afford a remarkable insight into the metaphysical symbolism of contemporary sculpture of the human figure’, Parr could not refrain from frankly stating that ‘Ipoustéguy is an audacious artist whose style is too histrionic for some tastes including, it must be admitted, my own’. Nonetheless, he concluded: ‘However, on this major work the expressive means are sustained by the magnitude of the theme and the result is most impressive’.4 Lenton Parr, undated letter in support of the acquisition of Death of the father, c. Feb. 1972.

Contemporary sculpture in Melbourne at this time, including that made by Parr, meant for the most part modernist, abstracted steel constructions that experimented with ‘burnished, polished, often brightly painted and welded industrial forms’ (although some artists, such as Les Kossatz and Peter Corlett, still worked in a figurative mode).5Rebecca Edwards & Beckett Rozentals, ‘Hard edge: abstract sculpture 1960s–70s’, National Gallery of Victoria, https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/hard-edge-abstract-sculpture-1960s-70s/. The new premises of the NGV, designed in a strikingly modernist style by Sir Roy Grounds, had only opened a few years previously in 1968. The building had a pared-back aesthetic that saw most of the ‘old-fashioned’ nineteenth-century narrative paintings banished from its walls, cast into the basement for decades in an area referred to by gallery staff as the ‘elephants’ graveyard’. In this climate, the NGV’s acquisition of a sculptural ensemble composed predominantly of hand-carved Carrara marble and imbued with both religious and Renaissance-evoking symbolism was bound to put a cat among the pigeons. Not surprisingly, therefore, the first public viewing of Death of the father in Melbourne in October 1972 ‘saw the art world erupt into a full-blown controversy’.6Hamilton.

The sculpture’s maker was born in 1920 at Dun-sur-Meuse in north-eastern France, the son of a French carpenter, Eugène Robert, and a Basque hairdresser, Madeleine Ipoustéguy. His youth was spent wandering the countryside close to Verdun, the site of intense conflict during the First World War, where the land was still pitted with funnel-like shapes that marked the impact of ordnance shells. ‘We were surrounded by the vestiges of war’, he later recalled. ‘As I walked over the ground, I realised I was treading upon death’.7Jean Ipoustéguy, Chroniques des jeunes années, 1997; quoted in Flavio Arensi & Pascal Odille (eds), Ipoustéguy. Eros + Thanatos, Palazzo Leone de Perego, Legnano and Allemandi & Co., Turin, 2008, p. 166. The theme of bodily decay, not surprisingly, informed his later art practice. In 1937 the family relocated to the outskirts of Paris where, a year later, having taken the wrong bus, the young Ipoustéguy accidentally discovered the school where the City of Paris was offering free evening classes in drawing. He enrolled for study under Robert Lesbounit. These studies were interrupted by the outbreak of World War Two, when he was mobilised into the army, eventually ending up in south-west France as an ironworker during the Vichy regime. After the war, back at evening classes in Paris, he was awarded the first prize for drawing in 1946. Lesbounit now encouraged him to drop his birth name, Jean Robert, and adopt instead his mother’s maiden name as an artist.

When Ipoustéguy first found his calling as a sculptor, he faced an immediate hurdle. As he summarised the situation:

It just so happened that when I started sculpting, the zeitgeist and fashion excluded the human figure from art. In the 1950s, to get round the language of the ‘abstract’, I took my own path: I sculpted cities, architectures, masses crossed by voids, which were geometrically inscribed in space. It was a way of learning my form and resisting this pressure, this ban on representing the body.8 ibid., p. 166.

A trip to Greece in the early 1960s, where he studied ancient Greek sculpture, consolidated his commitment to exploring the human body in his art, which was now informed by mythological and historical narratives in a series of large-scale bronzes. In August 1967 he travelled to Carrara in central Italy, a region whose quarries had been renowned for the quality of their marble since ancient Roman times. He was fascinated by Michelangelo’s use of this marble for his iconic High Renaissance sculptures such as La Pietà, 1498–99 (Saint Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City), and the colossal David, 1501–04 (Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence). He was also intrigued that use of this marvellous material in the twentieth century had largely dwindled to the production of cemetery memorials and interior tiling. Ipoustéguy spent a year working with the marble sculpture studios Laboratori Artistici Nicoli, perfecting his hand at direct marble carving. Many years later he recounted:

In Carrara I had success straight away, creating something worthwhile immediately. I’ve never had a problem with materials. I have always had a connection with them, have experienced something. I talk with metal, which tells me: You’re on the right track, go for it. And I listen to marble. When the size is right, I hear: yes, yes.9Jean Ipoustéguy, quoted in Françoise Monnin, Ipoustéguy sculpteur, Éditions Meuse/Serge Domini, Metz, 2003, p. 19.

While helpers from Nicoli would rough out the blocks that he chose from the quarry, he always worked alone on freeing the sculptures he envisaged emerging from within these, exploring the marble’s possibilities and releasing its translucent effects through direct carving with his own hands.10 Pierre Gaudibert, Ipoustéguy, Éditions Cercle d’art, Paris, 1989, p. 36.

The primary work that Ipoustéguy created at Carrara was Death of the father, an expansive installation composed of seventeen separate elements that together narrate an ambiguous scenario of devotion, decay and oedipal tension. At the centre of this tableau, described in the artist’s own words:

the father is lying on his back, his face and hands in silvered bronze, receiving the marmoreal presence of the son who, with a constraint around his neck, is suspended in an aggressive pose above him. He is surrounded by around ten mitred heads of popes, their faces compressed or disfigured, their skulls exposed.11 ibid., pp. 36, 38.

The central figure of the son is carved with Michelangesque gusto. He is shown crouching on his father’s coffin, whose cold metallic form resembles a mortuary operating table. He stares fixedly forward, towards the realistically rendered face and hands of the father, around whom irradiate a series of visages in progressive states of decomposition, the final of which is reduced to a dark steel perforated ball. With a nod to contemporary abstraction, these are situated upon smooth stainless-steel cones that are ‘sutured’ together, as if post-autopsy, below the neck. Their placement around the perimeter of the installation has been compared to the forms of pleurants (weepers), mourning figures that surrounded the central effigy of the deceased in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Burgundian tomb monuments (a working sketch for the installation has its composition arranged in this manner). The repeated, gleaming mitres placed atop these skulls punctuate the piece like Baroque trumpet blasts.

Reflecting on his unique figurative style, Ipoustéguy declared:

I see myself as somewhere between the Baroque, with its volcanic contouring that distributes light and shadow equally across sculpture, and Classicism, which removes as much shadow as possible from its volumes.12 Évelyne Artaud, interview with Jean Ipoustéguy, in Gaudibert, p. 134.

As the American writer John Updike put it:

Committed to restoring sculpture to a pre-Brancusi complexity, Ipoustéguy draws upon virtuosic resources that remind us of the Baroque masters, with their exuberant medleys of materials (metal, stone, colors of marble) and their ambitious assemblages of groups and entire environments.13 John Updike, Just Looking: Essays on Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1982, p. 165.

The elegiac yet chilling procession of decaying heads arranged around Death of the father’s central figure has been likened to ‘a field of corpses’, while the viewer is made ill-at-ease upon realising that the marble leg to the right of the son’s muscular but distorted torso belongs not to him, but to another, still cloaked, entity altogether.14 Bernd Krimmel, ‘Versuch über eine Bilderwelt’, in Ipoustéguy. Kunstpreis der Stadt Darmstadt, Kunsthalle Darmstadt, 1969, p. 10. ‘Even if my work is ambiguous’, Ipoustéguy stated in 1978:

I am expressing something that we all have and that is profoundly unknown, that escapes analysis. I bring the unknown, which belongs to everyone, which awakens, which provokes human unrest. This is also what often displeases, which seems intolerable [in my work], and not the nudity, immodesty or violence. It’s something else behind that.15 Geneviève Breerette, ‘Le Chant somptuaire du sculpteur. Un entretien avec Ipoustéguy’, Le Monde, 6 July 1978; reprinted in Ipoustéguy. Werke 1956–1978, Staatliche Kunsthalle Berlin, 1979, p. 22.

Death of the father was first exhibited at Galerie Claude Bernard in Paris in November 1968. It was included in a solo show devoted to works the artist had hand-carved at Carrara between August 1967 and September 1968. Another work from this exhibition, Chistera, 1967, was later donated to the NGV in 1993. The exhibition catalogue contained detailed photographs of Death of the father and an impenetrable text by French philosopher André Glucksmann. This catalogue was made available to NGV visitors in 1972, but only in the original French, as Glucksmann’s text ‘proved difficult to translate accurately’.16 André Glucksmann, ‘La Mort du père’, in Ipoustéguy. Marbres, Galerie Claude Bernard, Paris, 1968; Annette Dixon, ‘Hand sheet about Ipoustéguy’, The Age, Melbourne, 8 Nov. 1972.

After visiting the 1968 exhibition in Paris, critic Paul Waldo Schwartz wrote:

Jean Ipoustéguy’s performance at Galerie Claude Bernard is a remarkable foray, a magnificent indiscretion … The exhibition is all of Carrara marble and induced in a Renaissance light at that – which is strictly taboo, as Ipoustéguy knows full well … The conception is theatrical, but is also so in a magical sense, for the image of flesh which Ipoustéguy carries to tense extremes has again become, in time, a revelation and a shock. And a challenge. It is there less to be liked than to be necessary. Since one cannot be indifferent to it, nor turn from it, approval is dwarfed and condemnation irrelevant.

As for Death of the father: ‘In principle, what better employment for marble, the metaphor shifting between transience and permanence, less a return to a Renaissance presence than to a Michelangesque motive’.17 Paul Waldo Schwartz, ‘Paris commentary’, Studio International, vol. 176, no. 906, Dec. 1968, p. 268.

Ipoustéguy later recalled two strange encounters that occurred at this time:

In 1969, three young men coming out of the Claude Bernard gallery where I was exhibiting Death of the father approached me on the sidewalk and one of them said to me: ‘You can’t tell stories to children’. In fact, he was telling me that my sculpture had been accepted. Consideration sometimes took another form: three days later, as I was having a drink in a small bar-tabac in the rue de Seine, a young man leaned over my table and, looking me in the eye, said: ‘You, I’ll kill you…,’ adding, ‘with my sculpture.’ I advised him to get a revolver.18 Évelyne Artaud, “Ipoustéguy, parlons …”, Éditions cercle d’art, Paris, 1993, pp. 115–16.

The following year, American art critic Donald Millar proposed that Ipoustéguy’s work ‘over the last ten years, especially his large bronzes and more recent marbles, may be most fully appreciated as surreal expressions’. He saw in Death of the father ‘an erosion of faces reminiscent of Dalí’s cuttlebones and craniums’. He read further influence from Surrealism in how, in Ipoustéguy’s work, ‘usually a dream state prevails, or reality is made grotesque. There is a strong psychological disposition and often a sense of terror and the unknown’. In the Death of the father, in particular, Millar argued:

The carved sculptor’s abnormal eyes and mouth, the metamorphosis of his back which may be a double image of his chest, the great scar on the right forearm, the swollen penis all imply a variety of anxieties: great loss of a parent, the marks of a harsh past and a coming to power, physical as well as psychical, a confrontation and maturation.19 Donald Millar, ‘Ipoustéguy: the art of Astonishment’, Art International, Zurich, vol. 14, no. 2, Feb. 1970, pp. 44–45, 48.

For Jean-Dominique Rey, writing in Vie des arts in 1970:

This simultaneous recumbent figure, which is part exorcism and part stage production, part fantasy and part parody, multiplies, by placing them on shiny steel bases, polished marble heads embedded in identical mitres. Each marks a different degree of decomposition, the return to the ‘old ancestral foetus’, which the sculptor, stretched out nude, contemplates with a lucid eye. With its blend of horror and perfection, its contrast of subject and material, its juxtaposition of realism and distance, Death of the father remains Ipoustéguy’s most deliberately disturbing work.20 Jean-Dominique Rey, ‘Ipoustéguy: Un art qui fonce vers l’avenir’, Vie des arts, no. 61, winter 1970–71, p. 44.

The central figure of the son in Death of the father is a deliberate self-portrait of the artist, weighed down by the tools of his sculptural trade, placed like a yoke on either side of his neck. A page from a sketchbook Ipoustéguy worked in during the gestation of Death of the father is inscribed ‘Porte le bonheur de ton oeuvre dans ton coeur. Son fardeau sur ses épaules’ (Carry the happiness of your work in your heart. His burden on his shoulders).21 Jean Ipoustéguy, Carnet rouge (Red sketchbook), 1967–68, Estate of Jean Ipoustéguy collection.

Ipoustéguy’s sculptures routinely spent a long time in development. ‘Usually, the first idea, the source idea of work that I have in my hands dates back several years,’ he is recorded as saying. ‘Usually, while working on one thing, I’m thinking mainly about an important piece that I’m going to do later. Not my next sculpture. The one after, maybe’.22Jean Ipoustéguy, quoted in Walter Lewino, Ipoustéguy, Galerie Claude Bernard, Paris, 1966. Death of the father developed out of a series of paintings created by Ipoustéguy in response to the death of Pope John XXIII in 1963. It was some years later that the artist studied an issue of the French illustrated journal Paris Match that was devoted to the lying-in-state and funeral of John XXIII. Struck by the pageantry of this spectacle, he undertook a series of Death of the Pope paintings prior to travelling to Carrara in 1967. ‘I found this rite quite impressive,’ he recounted, ‘a rite that comes from the depths of the ages, with all the bishops around, who are themselves marked as people who are also going to disappear, their flesh is going to dissolve’.23 Jean Dèves, interview with Jean Ipoustéguy, 2003, broadcast as part of France Culture’s Mémorables series on Radio France in 2006. I thank Marie-Pierre Robert for sharing this broadcast. In this context, the arrangement of the sculptural installation that he began at Carrara in the form of a religious basilica was perfectly logical.

While the artist was working at Carrara in 1968, his father died. Ipoustéguy had often repeated a story about how, at the time he started sculpting:

My father was a manual worker and carpenter, and he was very worried about my future. And one day I said to him at the dinner table, don’t worry, I’ll make you into a pope.24 Jean Ipoustéguy, quoted in La Mort du père (1968) de Jean Ipoustéguy, 1974, Bertrand Renaudineau, 14 min. I thank Marie-Pierre Robert for sharing this film.

Before the burial he made life moulds of his father’s face and hands. These were subsequently cast in silvered bronze and inserted into his sculptural ensemble, which now morphed from Death of the Pope into Death of the father. A moving page from Ipoustéguy’s Carrara sketchbook is inscribed ‘à la mémoire du père’ (in memory of my father) and bears a drawing of his father’s face in the repose of death. ‘I had my dead father in front of me’, he lamented, ‘and it’s still hard to talk about. I said “I will keep my promise. I will make you into a pope”.’25ibid.

This sketchbook also contains a clipping from a November 1967 issue of the newspaper Le Monde, advertising Robert Merle’s Un animal doué de raison (A Sentient Animal), illustrated with two dolphins. This novel, which had just been published, was a thriller that focused upon the intelligence of dolphins and their potential use as trained instruments of warfare. The same sketchbook bears a thought jotted down by Ipoustéguy that seems to relate to this: ‘l’objectivité que de donne la collectivité sociale’ (the objectivity given by social community).26 Ipoustéguy, Carnet rouge.

It is fascinating to consider whether Ipoustéguy may have thought at the time that the basilica-like shape of his Death of the father installation also resembled the movement of a pod of dolphins through the ocean, the hierarchical structure of the Catholic church’s processions and rituals mirroring the collective social structure of dolphin communities travelling together for mutual benefit and support. The artist’s daughter Marie-Pierre Robert has noted how ‘the dolphins photographed, with their shiny diaphanous skin, resemble the double mitres of bishops, tilted at an angle’.27 Correspondence with Marie-Pierre Robert, 20 Feb. 2024. Or may he have been thinking of himself as heir to his father’s legacy, Eugène Robert’s dauphin – due to the manner in which heirs to the French throne were traditionally known as ‘le Dauphin’ (The Dolphin) and bore dolphins as their regal symbol, a practice that descended from the Dauphiné region on the Mediterranean in southern France?28 See Alan Rauch, Dolphin, Reaktion Books, London, 2014, pp. 93, 106. Against this harmonious and noble suggestion, however, stands this oedipal declaration from the artist:

His son, that’s me, murdering his father. The father is going to die … The one who happens to be on top is the father’s killer … I’m finishing off my father. I’ll be finished off by my own children.29 Dèves, interview with Jean Ipoustéguy.

The National Gallery of Victoria chose to unveil its acquisition of Death of the father with a splash on 24 October 1972, displaying it in a dedicated temporary exhibitions gallery, where it was placed at the centre of a theatrical son-et-lumière installation. Here, the lights were dramatically lowered at ten-minute intervals, casting the sculptural grouping into compelling chiaroscuro. This was accompanied by a musical soundtrack.

Son-et-lumière installation of Death of the father, National Gallery of Victoria, Oct–Nov. 1972

The next day, the thirty-year-old art critic for The Age, Patrick McCaughey, came out swinging. While that newspaper’s front page featured a huge close-up image of the sculpture, inside its pages McCaughey launched a highly vituperative attack upon both the artist and the work itself. ‘Who is Ipoustéguy? You may well ask’, he thundered, continuing:

He is a minor European sculptor on which the National Gallery has chosen to lavish the largest single expenditure of its own funds. They have confused the call to be bloody, bold and resolute with being merely bloody silly. If you really wanted an Ipoustéguy, and he could hardly be regarded as a pressing need, why spend so extravagantly in acquiring this vast tomb of his sculpture? … The sculpture itself, in gleaming white marble on aluminium canisters (get it, ‘the old and the new …’), is just a stagey spectacle … What can one say about such vulgarity? The slickness is astonishing as the marble drips and shines like plastic. But the slickness is nothing to the corniness … It is the re-run in the 1970s of that good old 19th century spectacle and crowd pleaser, the tableau vivant. Madame Tussaud enters the National Gallery of Victoria.30 Patrick McCaughey, ‘National Gallery buys a what?’, The Age, Melbourne, 25 Oct. 1972.

McCaughey’s caustic diatribe was juxtaposed with a statement from the NGV’s director, Eric Westbrook, who declared Death of the father to be ‘an absolutely stunning, marvellous work’.31 John Messer, ‘It’s marvellous, says art chief’, The Age, 25 Oct. 1972. The highly respected sixty-five-year-old critic for The Herald, Alan McCulloch, hailed the acquisition, declaring:

This gigantic tour de force in polished Carrara marble well illustrates the reasons for Ipoustéguy’s rise to fame as one of the world’s leading figurative sculptors … It is an extraordinary work, an exhortation perhaps to consider the transience of the flesh as opposed to the permanence of the spirit.32 Alan McCulloch, ‘A bridge to new realism’, The Herald, Melbourne, 25 Oct. 1972.

The battle lines were now drawn, and controversy raged about the new sculpture for months. Acknowledging that Death of the father ‘has dropped like a lump of lead into preconceptions’, Annette Dixon defended its purchase, declaring:

A thing like this causes a bit of a pain to supporters of abstract sculptures. This is a monumental and complex piece of very high quality combining the figurative and the abstract. It is a cerebral piece, but passionate. It borders on poetry.33 Laurie Thomas, ‘Why? critics ask after gallery pays $60,000 for sculpture’, The Australian, Sydney, 26 Oct. 1972.

Elsewhere, she was quoted as saying:

I think new attitudes and new approaches are always painful to some people – particularly people involved in the art world. I believe in the sculpture. I think it is modern, new, and contains a great deal of humanity. The ordinary people who have seen it – the men lifting it into position, the electricians adjusting the gallery lights, say that the sculpture has given them a great deal of pleasure.34Hamilton.

The president of the NGV’s council of trustees, N. R. Seddon, questioned the propriety of McCaughey’s review:

Does he really have to be so discourteous in his comments? To write of the gallery as being ‘bloody silly’ is gratuitously offensive; to refer to ‘extravagant and ignorant squandering’ is equally offensive and suggests a claim to omniscience which is totally unwarranted.35 N. R. Seddon, ‘Gallery replies to a diatribe’, The Age, 1 Nov. 1972.

Meanwhile, a Jane Semler of Ivanhoe wrote a stern letter to The Age, rebuking its critic’s superiority on aesthetic matters:

The sculpture is enormous in concept and craftsmanship, and will be with us much longer than Mr. McCaughey. Michelangelo was lucky that Mr. McCaughey did not live in his time when he finished David, which in its new concept was lambasted by those in the know. The world of today would be poorer if the McCaugheys of that time had had their wish.36Jane Semler, ‘Letter to the editor: Michelangelo was lucky he missed McCaughey’, The Age, 31 Oct. 1972.

A young Maureen Gilchrist, then a student in the Fine Arts Department at the University of Melbourne, sprang to McCaughey’s defence:

Mr. McCaughey’s newspaper criticism of largely contemporary art is undoubtedly the most ‘with-it’ of its kind in this country. If anyone is qualified to assess contemporary achievements both internationally and nationally, it is Mr. McCaughey. His scholarship in the matter is considerable and the gallery buyers would be doing such scholarship in this country a great service if they heeded his criticism instead of remaining blandly unresponsive to the last.37M. Gilchrist, ‘Critics qualified and unqualified’, The Age, 4 Nov. 1972.

Ever the diplomat, Alan McCulloch devoted a second article to the sculpture, pondering whether it was ‘Literary paradox, meaningful masterpiece, magnificent failure? As the weaknesses are weighed against the strengths, opinions will no doubt veer this way and that’. He argued forcefully, though, that:

to fully appreciate ‘La Mort du Pere’ we must go back to the days when all respectably trained art students engaged in exhaustive studies of human anatomy … Many a hopeful career foundered before its complex system of sinews and muscles, and few were able, subsequently, to turn this charnel house exercise to advantage. One who has is Ipousteguy. And in the context of modern sculpture this accomplishment places him in a category apart. Ipousteguy is a risen Lazarus. And perhaps for that reason is viewed by many with wonder and some with horror.38 Alan McCulloch, ‘Ipousteguy: meaningful masterpiece or magnificent failure?’, The Herald, Melbourne, 1 Nov. 1972.

Annette Dixon responded graciously to the controversy that swirled around the acquisition of Death of the father, stating that ‘[s]pirited and divergent reactions are a good indication that a contemporary work of art has some value and I am delighted to see that the sculpture has aroused so much interest’.39 Dixon, ‘Hand sheet about Ipousteguy’. Privately, however, she was later to write to Ipoustéguy, in perfect French, expressing her disdain for the state of art criticism in this country:

The sculpture made an extraordinary impression here, and we’re just recovering from that little upheaval. After all, a work of art has to be very powerful to shake up deep-rooted ideas. I have kept for you some reviews and photographs that have appeared in the newspapers, if you would like to have them as a souvenir. However, it is absolutely forbidden to have the nonsense of our art critics translated into French.40 Annette Dixon, letter to Jean Ipoustéguy, 26 April 1973. NGV curatorial files.

Also privately, she received letters of support from Melbourne sculptor Phillip Cannizzo, and from the inaugural director of the recently opened Harry McLelland Art Gallery in Langwarrin, Carl Andrew, who confessed to her:

I will admit that on the evidence of a few very inadequate photographs I was somewhat dubious about the work. But confrontation with the real thing was a moving experience. I consider it undoubtedly to be one of the most important works in Australia.41 Phillip Cannizzo, undated letter to Annette Dixon; Carl Andrew, letter to Annette Dixon, 26 Oct. 1972. NGV curatorial files.

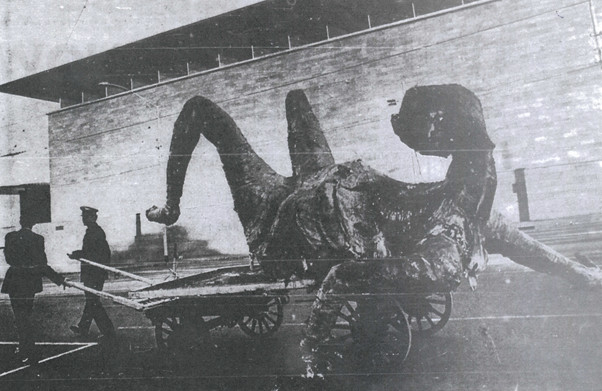

Within days of Death of the father being unveiled, a hilarious ‘critique’ of the gallery’s new sculpture arrived in the form of a 3-metre-tall papier-mâché ‘monster’ painted in red and green splotches. It was left at dawn at the NGV’s entrance on a four-wheeled bullock dray, accompanied by a brick, a petrol can and a tuft of grass. The work of a group calling itself the Melbourne Revolutionary Surrealist Society and titled ‘Death of Capitalism’, this ‘monster’ was classed as an obscene object and taken into protective custody by the South Melbourne police department. The NGV’s director, Eric Westbrook, jovially remarked at the time:

It is a pity that the police regard it as litter. I am glad that there is some reaction to our new Ipousteguy sculpture. If a group feels strongly enough to do something like this, it’s good. Art is something about which people should feel strongly.41 Eric Westbrook, quoted in ‘Hey D24 … We’ve nabbed a monster!’, The Herald, Melbourne, 28 Oct. 1972. See also ‘Is it art, litter, or obscene …?’ The Sun-Herald, Sydney, 29 Oct. 1972.

‘Death of Capitalism’ being arrested by South Melbourne police, 6.15 am, 28 Oct. 1972

Reporting on the arrival of this monstrous, alien-like form on the gallery’s doorstep, The Bulletin noted that ‘Eric Westbrook was thrilled. This was just the extra boost he needed. “La Mort du Pere” is now a bigger drawcard than Bazza Mackenzie’. Remarking that ‘the cost of the sculpture represents 300,000 20-cent entry fees’, The Bulletin also observed:

Melbourne is a city which normally only gets disturbed over deeply important matters – the quality of edible shark, the price of meat pies and the sentences handed out to footballers by the tribunal on Tuesday nights. So it is awfully good to see the citizens in a state of conflicting fury over a piece of modern sculpture … but the controversy has been splendid for business. When your correspondent was there the crowds were practically queuing up to get in. One young lady said: ‘I like it. It reminds me of the big marble job in Rome. You know the one I mean, the big thing with the fig leaf’.43‘Out and about with Batman: masterpiece or failure’, The Bulletin, 11 Nov. 1972, p. 9. The Adventures of Barry McKenzie, directed by Bruce Beresford, had just been released in Australian cinemas at this time.

Another local newspaper noted how ‘Elizabeth Dean, 11, of St Mary’s School, Colac, fell in love with it at first sight, saying ‘“If there was enough space, I’d love to have it in my room”’. Undertaking direct research, the paper also told its readers:

The attendant who has guarded the sculpture for seven hours a day for the past three weeks claims that ‘90 per cent’ of the public like it. But whatever the final verdict, the National Gallery isn’t going to have any regrets. ‘Death of the Father’ is bringing them through the turnstiles at the rate of 700 more a day above the normal rate.44 Jill Graham, ‘$60,000 in polished marble and steel: Ipousteguy’s Death of the father. Just stone and metal, or?’, Postscript Weekender, Melbourne, 30 Nov. 1972.

The Age informed its readers that ‘housewives, businessmen, students, artists, schoolchildren and tourists swarmed into the crypt-like atmosphere of the Temporary Exhibitions Gallery to peer at the work’, while The Sun reported, ‘“It’s spooky, like something out of a horror film”, a little girl thought of Victoria’s latest art purchase’.45 Kevin Childs, ‘Good or bad they flock to see THAT work of art’, The Age, 26 Oct. 1972; ‘Art? It’s spooky, says a critic’, The Sun, Melbourne, 26 Oct. 1972.

Death of the father was championed by the Sun newspaper’s art critic Jeffrey Makin. Under a headline pronouncing that ‘The “Death” will silence critics’, he somewhat ponderously proclaimed:

Ipoustéguy’s ‘Death of the Father’ at the National Gallery is one of the most important art purchases yet made by an Australian gallery. It is a work that exists beside those of Rodin, Moore, Rembrandt, Carracci and Bonnard. It needs no written justification. Like most great works, it has a presence – a right of being. This presence eventually will silence all its critics into mute admiration. Even now its reputation is the beginning of legend.

He took issue with the work’s display, however, noting:

The spot lighting is too theatrical. It really needs to be seen in a courtyard situation with its centre of gravity up to eye level. This means a platform. Other than that it’s a breathtaking experience.46Jeffrey Makin, ‘The “Death” will silence critics’, The Sun, Melbourne, 1 Nov. 1962.

The NGV’s acquisition of Ipoustéguy’s sculpture had become ‘the bête noire of the local art scene’, according to local art critic Terry Whelan:

Personally, I think it is a good thing. It has led to a revitalization of our aesthetic thinking. Sixty-thousand dollars may sound a Croesus-like ransom to pay for an expensive send-up of Manzu’s ‘Cardinals’. However, it has removed the cobwebs from our thinking. It has provided the opportunity to re-examine our aesthetic theories, the role of the gallery in artistic circles, and even our purchasing policies. The number of people, nonetheless, who out of aesthetic bigotry, have refused to accept it as a work of art merely magnifies our provincialism. Whether it is good or bad art is, of course, a separate debate.47 Terry Whelan, ‘The arts’, Toorak Times, Melbourne, 8 Nov. 1972.

The controversy made headlines in various countries around the world, from the Philippines to Bangladesh, in a syndicated article in which Annette Dixon was quoted as saying, ‘Like me, the ordinary people who are streaming into the gallery appear to love it. It has created more interest with the public than any other single work we have exhibited here for many years’.48‘Australian gallery acquires controversial French sculpture’, The Philippines Daily Express, Manila, 15 Jan. 1973; ‘Controversial French sculpture for Australian gallery’, The Bangladesh Observer, Dhaka, 18 Feb. 1973. Newspapers and tabloids alike delighted in photographing children interacting with the sculpture, all of them seemingly oblivious to Death of the father’s erotic content. Only one satirical article, in the iconoclastic Nation Review, addressed this, wickedly describing it as ‘[s]ixty thousand dollars of your cash and mine [spent] on a truncated bloke with a hard on, leering unnaturally at his dead dad’.49 Ted Neilson, ‘Ipousteguy with red Qantas inflight relaxa-sox’, Nation Review, Melbourne, 11–17 Nov. 1972.

After being displayed for one month in the Temporary Exhibitions Gallery, the Ipoustéguy was moved to the NGV’s Modern European Gallery on the second floor.50 Annette Dixon, ‘Notes on the Gallery’s collections: La Mort du Père (Death of the father)’, Bulletin of the National Gallery Society of Victoria, Dec. 1972, p. 3. In January 1973, it was noted:

since La Mort du Pere went on exhibition late in October 1972 it has been the centre of a controversy among Australian art critics. Some love it, some hate it. The general public is going in droves to the gallery to see it.51‘Controversial sculpture for Victoria’, Australian News, Melbourne, 11 Jan. 1973.

It would certainly have made sense to keep the sculpture on view for the 40th International Eucharistic Congress, which was held in Melbourne in February 1973, bringing thousands of international Catholic visitors to the city, along with ‘17 cardinals, five cardinals select and hundreds of archbishops and lower-ranking clergy’, along with global religious superstar Mother Theresa.52 Robert Trumbull, ‘Catholic congress opens in Melbourne’, The New York Times, 19 Feb. 1973, p. 8.

In early 1973 it was hoped that Ipoustéguy would soon visit Melbourne. Annette Dixon envisaged that he might visit with two Italian bronze casters, Fernando Romei and Vittorio Carboni, who ran the Vittorio & Fernando Art Foundry in Moorabbin and were great admirers of his work. And she had another project in mind:

Now that everyone here has had time to look at and think about Death of the father, I would like to ask you some general questions about your work and some more specific questions about the gestation of Death of the father. A tape-recording would be the best way to make such documentation. If you agree, I will prepare questions in advance and in case you don’t want to answer any, we can cross out those that are untenable. A recording of this kind will serve to avoid misunderstandings that may be published in the future and will provide a good basis for further research.53 Annette Dixon, letter to Jean Ipoustéguy, 26 April 1973.

Unfortunately, this trip was never undertaken due to health problems the artist was having with his kidneys, and then prior commitments to another project in Germany. A golden opportunity to capture Ipoustéguy’s personal reminiscences about the controversial new sculpture in Melbourne was thus lost.

Attacks on Ipoustéguy resurfaced eighteen months later, when Melbourne’s Tolarno Galleries staged a commercial exhibition of the artist’s sculptures and drawings at its premises in St Kilda. The NGV acquired Study of a woman, 1970, a sensuous nude charcoal drawing from this show, which was opened by the gallery’s president of trustees, N. R. Seddon. The newly appointed art critic for The Age, Maureen Gilchrist, however, delivered an excoriating critique of what she called Melbourne’s ‘second opportunity to examine the sculptural sins of this minor European figure’. Declaring Ipoustéguy to be ‘the most grandiose and obtrusively eclectic of latter-day monolithic sculptors’, Gilchrist argued that ‘the sculptor’s second coming to this city can serve only to emphasise the folly’ of the NGV’s acquisition of Death of the father two years previously. Her vehement denunciation of the artist’s work was extraordinarily severe:

None of Ipoustéguy’s achievements is worth much serious consideration. They are too derivative and over-dramatic. Ipoustéguy’s rhetoric comes straight from the nineteenth century. Indeed all his effects belong to outworn conventions of the past. The works are dogged by literary and art historical allusions.54 Maureen Gilchrist, ‘Ipoustéguy’s sculptural sins come up for a second viewing’, The Age, Melbourne, 8 May 1974.

Ironically these qualities, anathema to both McCaughey and Gilchrist – young critics writing in an Australia that had only recently embraced abstract expressionism and conceptual art – are precisely what make Ipoustéguy’s work so compelling today, when the hegemony of Greenbergian formalist aesthetics and the tyranny of modernism’s reductive view of art history have been cast aside. Journalist Terry Ingram summarised the situation in 1972 neatly, when he wrote: ‘Working as a figurative sculptor, Ipoustéguy will be old hat to critics who believe that everything that can be said about the human form has been said’.55 Tony Maiden & Terry Ingram, ‘It may be a boo boo, but … Melbourne “bargain” rakes in the cash’, The Financial Review, Sydney, 27 Oct. 1972.

In 1972 Patrick McCaughey disparagingly predicted:

The cold comfort of the matter is this: there’s nowhere big enough in the gallery to display the thing so it will hopefully only be dragged out for great occasions like Ipoustéguy’s birthday or, perhaps, Father’s Day.56 McCaughey, ‘National Gallery buys a what?’

History has proven him wrong. While records of how frequently Death of the father was displayed in the 1970s and 1980s are not available (although the author of this article recalls seeing it on several occasions during those decades), in recent years the sculpture has been placed on view at NGV International in 2011, 2012, 2017 and 2020. In 1998, it was featured in a large survey show of world religious art organised at the NGV by Sister of Mercy and art historian Rosemary Crumlin, Beyond Belief: Modern Art and the Religious Imagination. At that time Geoffrey Edwards, the gallery’s Senior Curator of Sculpture and Glass, acknowledged:

Given the formal and material austerity that characterise much twentieth-century sculpture, Ipoustéguy’s richly symbolic magnum opus is a difficult work to assimilate within the modernist canon. To a degree its epic scale, unexpected conjunction of media, and deployment of ‘serial’ elements relate to the idiom of ‘installation’. However, such a notion is plainly inconsistent with a tour de force of figurative marble carving.57. Geoffrey Edwards, ‘Jean-Robert Ipoustéguy … the silent silvered features of the father’, in Rosemary Crumlin (ed), Beyond Belief: Modern Art and the Religious Imagination, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1998, p. 122.

Interviewed in 1993, Ipoustéguy declared that if he had not become an artist, he would have liked to have been a musician or a gangster.58 Artaud, “Ipoustéguy, parlons …” Arguably, he achieved both these aims with Death of the father, a work that assaults the sensibility of some, but to others soars visually to Wagnerian heights.

Dr Ted Gott is Senior Curator, International Art at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Author’s note: I warmly thank the artist’s daughter, Marie-Pierre Robert, for her generous assistance with the research and writing of this article. All translations from the French are my own. Where quotations are drawn from contemporary Australian press coverage, these do not include French accents or correct orthography, as these were not used in local newspapers at this time.

Notes

John Hamilton, ‘Art? It was love at first sight’, The Herald, 25 Oct. 1972.

Annette Dixon, Jean Ipoustéguy, Submission for Acquisition, 15 Feb. 1972.

Hamilton.

Lenton Parr, undated letter in support of the acquisition of Death of the father, c. Feb. 1972.

Rebecca Edwards & Beckett Rozentals, ‘Hard edge: abstract sculpture 1960s–70s’, National Gallery of Victoria, https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/hard-edge-abstract-sculpture-1960s-70s/.

Hamilton.

Jean Ipoustéguy, Chroniques des jeunes années, 1997; quoted in Flavio Arensi & Pascal Odille (eds), Ipoustéguy. Eros + Thanatos, Palazzo Leone de Perego, Legnano and Allemandi & Co., Turin, 2008, p. 166.

ibid., p. 166.

Jean Ipoustéguy, quoted in Françoise Monnin, Ipoustéguy sculpteur, Éditions Meuse/Serge Domini, Metz, 2003, p. 19.

Pierre Gaudibert, Ipoustéguy, Éditions Cercle d’art, Paris, 1989, p. 36.

ibid., pp. 36, 38.

Évelyne Artaud, interview with Jean Ipoustéguy, in Gaudibert, p. 134.

John Updike, Just Looking: Essays on Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1982, p. 165.

Bernd Krimmel, ‘Versuch über eine Bilderwelt’, in Ipoustéguy. Kunstpreis der Stadt Darmstadt, Kunsthalle Darmstadt, 1969, p. 10.

Geneviève Breerette, ‘Le Chant somptuaire du sculpteur. Un entretien avec Ipoustéguy’, Le Monde, 6 July 1978; reprinted in Ipoustéguy. Werke 1956–1978, Staatliche Kunsthalle Berlin, 1979, p. 22.

André Glucksmann, ‘La Mort du père’, in Ipoustéguy. Marbres, Galerie Claude Bernard, Paris, 1968; Annette Dixon, ‘Hand sheet about Ipoustéguy’, The Age, Melbourne, 8 Nov. 1972.

Paul Waldo Schwartz, ‘Paris commentary’, Studio International, vol. 176, no. 906, Dec. 1968, p. 268.

Évelyne Artaud, “Ipoustéguy, parlons …”, Éditions cercle d’art, Paris, 1993, pp. 115–16.

Donald Millar, ‘Ipoustéguy: the art of Astonishment’, Art International, Zurich, vol. 14, no. 2, Feb. 1970, pp. 44–45, 48.

Jean-Dominique Rey, ‘Ipoustéguy: Un art qui fonce vers l’avenir’, Vie des arts, no. 61, winter 1970–71, p. 44.

Jean Ipoustéguy, Carnet rouge (Red sketchbook), 1967–68, Estate of Jean Ipoustéguy collection.

Jean Ipoustéguy, quoted in Walter Lewino, Ipoustéguy, Galerie Claude Bernard, Paris, 1966.

Jean Dèves, interview with Jean Ipoustéguy, 2003, broadcast as part of France Culture’s Mémorables series on Radio France in 2006. I thank Marie-Pierre Robert for sharing this broadcast.

Jean Ipoustéguy, quoted in La Mort du père (1968) de Jean Ipoustéguy, 1974, Bertrand Renaudineau, 14 min. I thank Marie-Pierre Robert for sharing this film.

ibid.

Ipoustéguy, Carnet rouge.

Correspondence with Marie-Pierre Robert, 20 Feb. 2024.

See Alan Rauch, Dolphin, Reaktion Books, London, 2014, pp. 93, 106.

Dèves, interview with Jean Ipoustéguy.

Patrick McCaughey, ‘National Gallery buys a what?’, The Age, Melbourne, 25 Oct. 1972.

John Messer, ‘It’s marvellous, says art chief’, The Age, 25 Oct. 1972.

Alan McCulloch, ‘A bridge to new realism’, The Herald, Melbourne, 25 Oct. 1972.

Laurie Thomas, ‘Why? critics ask after gallery pays $60,000 for sculpture’, The Australian, Sydney, 26 Oct. 1972.

Hamilton.

N. R. Seddon, ‘Gallery replies to a diatribe’, The Age, 1 Nov. 1972.

Jane Semler, ‘Letter to the editor: Michelangelo was lucky he missed McCaughey’, The Age, 31 Oct. 1972.

M. Gilchrist, ‘Critics qualified and unqualified’, The Age, 4 Nov. 1972.

Alan McCulloch, ‘Ipousteguy: meaningful masterpiece or magnificent failure?’, The Herald, Melbourne, 1 Nov. 1972.

Dixon, ‘Hand sheet about Ipousteguy’.

Annette Dixon, letter to Jean Ipoustéguy, 26 April 1973. NGV curatorial files.

Phillip Cannizzo, undated letter to Annette Dixon; Carl Andrew, letter to Annette Dixon, 26 Oct. 1972. NGV curatorial files.

Eric Westbrook, quoted in ‘Hey D24 … We’ve nabbed a monster!’, The Herald, Melbourne, 28 Oct. 1972. See also ‘Is it art, litter, or obscene …?’ The Sun-Herald, Sydney, 29 Oct. 1972

‘Out and about with Batman: masterpiece or failure’, The Bulletin, 11 Nov. 1972, p. 9. The Adventures of Barry McKenzie, directed by Bruce Beresford, had just been released in Australian cinemas at this time.

Jill Graham, ‘$60,000 in polished marble and steel: Ipousteguy’s Death of the father. Just stone and metal, or?’, Postscript Weekender, Melbourne, 30 Nov. 1972.

Kevin Childs, ‘Good or bad they flock to see THAT work of art’, The Age, 26 Oct. 1972; ‘Art? It’s spooky, says a critic’, The Sun, Melbourne, 26 Oct. 1972.

Jeffrey Makin, ‘The “Death” will silence critics’, The Sun, Melbourne, 1 Nov. 1972.

Terry Whelan, ‘The arts’, Toorak Times, Melbourne, 8 Nov. 1972.

‘Australian gallery acquires controversial French sculpture’, The Philippines Daily Express, Manila, 15 Jan. 1973; ‘Controversial French sculpture for Australian gallery’, The Bangladesh Observer, Dhaka, 18 Feb. 1973.

Ted Neilson, ‘Ipousteguy with red Qantas inflight relaxa-sox’, Nation Review, Melbourne, 11–17 Nov. 1972.

Annette Dixon, ‘Notes on the Gallery’s collections: La Mort du Père (Death of the father)’, Bulletin of the National Gallery Society of Victoria, Dec. 1972, p. 3.

‘Controversial sculpture for Victoria’, Australian News, Melbourne, 11 Jan. 1973.

Robert Trumbull, ‘Catholic congress opens in Melbourne’, The New York Times, 19 Feb. 1973, p. 8.

Annette Dixon, letter to Jean Ipoustéguy, 26 April 1973.

Maureen Gilchrist, ‘Ipoustéguy’s sculptural sins come up for a second viewing’, The Age, Melbourne, 8 May 1974.

Tony Maiden and Terry Ingram, ‘It may be a boo boo, but … Melbourne “bargain” rakes in the cash’, The Financial Review, Sydney, 27 Oct. 1972.

McCaughey, ‘National Gallery buys a what?’.

Geoffrey Edwards, ‘Jean-Robert Ipoustéguy … the silent silvered features of the father’, in Rosemary Crumlin (ed), Beyond Belief: Modern Art and the Religious Imagination, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1998, p. 122.

Artaud, “Ipoustéguy, parlons …”.