A large and complex painting first shown at Thomas Agnew’s and Sons in London in 1906, Charles Mackie’s Musical moments, 1905, is indebted to the artist’s study of Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (The ladies-in-waiting), 1656 (Museo del Prado, Madrid), which Mackie had copied in Madrid in 1904. The setting is probably the Waddell School of Music in Edinburgh, founded in the late 1870s by the balding violinist in the middle distance of Mackie’s composition, William Waddell, who appears with his wife Patricia Jessie Macnee seated at the piano. Their daughter Mary Elizabeth (Maimie), who later took over the running of the school with her sister Ruth, is the elegantly dressed seventeen-year-old seated at the front left, her violin resting gently in her lap between lessons.

Charles Hodge Mackie was born at Aldershot, Hampshire, in 1862, the son of a Scottish army officer of the 2nd Queen’s Royal Regiment of Foot. His father subsequently relocated the family to Edinburgh, where Mackie was schooled at George Watson’s College and, briefly, at Edinburgh University where he studied medicine. Art being his true calling, in 1878 at the age of sixteen he enrolled at the Trustees Drawing Academy of Edinburgh (later the Edinburgh College of Art). In 1882, he entered the life class at the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, where landscape artist William McTaggart was one of his teachers. In 1884, he was joint winner of the RSA’s Stuart Prize.1J. Lawton Wingate, ‘[Charles H. Mackie Obituary]’, 93rd Annual Report of the Council of the Royal Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 1920, p. 11. From 1880, when he was still a student, Mackie began contributing work to the annual exhibitions of the Royal Scottish Academy. His paintings of the 1880s were lyrical, atmospheric landscape studies that were in the naturalist tradition, popular in Scotland at that time.

In 1891, Mackie married Anne MacDonald Walls, sister of his artist colleague William Walls. The following year the Mackies visited London and then travelled to France, exploring the countryside of Normandy and Brittany. At Huelgoat in the latter province, they met French painter Paul Sérusier. In 1893 and 1894 they returned to Paris, socialising with Sérusier who now introduced them to other members of the emerging Nabi groupThe Nabis were an artists’ group formed in Paris in the late 1880s whose members were devoted to encouraging each other to be groundbreaking and transformative in their approach to art. They adopted a name, Les Nabis, from the Arabic and Hebrew words for prophet. – Paul Ranson, Edouard Vuillard – as well as to Paul Gauguin, whose studio they visited in April 1894.2Pat Clark, People, Places & Piazzas. The Life & Art of Charles H. Mackie, Sansom & Co., Bristol, 2016, p. 53. See also Belinda Thomson, ‘ “When the girls come out to play”: Edouard Vuillard and Charles Hodge Mackie, a reattribution’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 149, no. 1253, Aug. 2007, pp. 551–3. In Paris, Mackie also began to collect Japanese colour woodblock prints. Between 1900 and 1912, he created an impressive number of large-scale colour woodblock prints; they were distinguished by their lack of use of standard black key blocks to define the composition and also by their large number of individual blocks used to print coloured shapes, which were carefully juxtaposed side by side. Mackie referred to his colour woodblock technique as ‘an emotional use of the printing press, differing from painting only in block-shapes being used instead of brush-marks’.3Charles Mackie, in Malcolm C. Salaman, The Graphic Arts of Great Britain. Drawing, Line-engraving, Etching, Mezzotint, Aquatint, Lithography, Wood-engraving, Colour-printing, The Studio, London, 1917, p. 114. See also Malcolm C. Salaman, ‘Wood-Engraving for Colour in Great Britain’, The Studio, vol. 58, no. 242, May 1913, pp. 295–6; and W. B. C. Mackie, ‘Colour printing by Charles H. Mackie, RSA’; manuscript, copy artist file, National Gallery of Victoria.

In 1900, Mackie was elected Chairman of the Society of Scottish Artists and, in 1902, he was made an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh (of which he became a full member in 1917). In 1902, he was also elected to the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour, in recognition of his equal excellence in that field of art. In 1904 Mackie was commissioned by the Scottish artist and explorer William Gordon Burn Murdoch to paint a copy of Velázquez’s Las Hilanderas (The spinners), 1655–60 (Museo del Prado, Madrid). He travelled to Madrid, where he also painted a copy of Velázquez’s Las Meninas (The ladies-in-waiting), 1656, at the Prado.

In July 1906 the Dundee Evening Telegraph and Post informed its readers that

A second important picture has been secured for the Public Gallery at Melbourne from among those which formed the exhibition of ‘Independent Art of Today’ in Old Bond Street a new months since. It is the ‘Musical Moments’ of Mr Charles H. Mackie, who has for some years been an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy. The canvas, which had a place of honour at the end of the Gallery, was the largest picture in the show, and greatly admired. It is of a group of musical amateurs, young men and girls, pausing in the interval of a trio, some standing, some seated, in a room to which bright afternoon sunlight is admitted through two low windows. It is generally voted a most deft and successful rendering of a by no means easy subject. The treatment of the light is the real theme. Till the picture was seen in Bond Street Mr Mackie was very little known to London connoisseurs. Yet another picture by a Scotsman has been bought for Melbourne — the ‘Good Morning’ of Mr Harrington Mann, which was in the Royal Academy last year.4‘Scottish pictures for Melbourne’, The Evening Telegraph and Post (Dundee, Scotland), 12 Jul. 1906, p. 2.

Noting the novelty of seeing fresh works by little known northern painters in the 1906 Some Examples of the Independent Art of Today exhibition held at Thomas Agnew’s and Sons, London, The Observer (1906) gave Mackie’s painting a somewhat qualified reception:

Among the Scottish painters at this exhibition are three whose work is unfamiliar to the London public — Mr. C. H. Mackie, Mr. Robert Burns and Mr. W. McTaggart. The first of these is showing an admirable study of conflicting lights in the large canvas ‘Musical Moments’, the weakest point of which is the stiff pose of the principal figure.5‘Art exhibitions. Younger school echoes of Old Masters’, The Observer, 11 Feb. 1906, p. 6.

The Times critic (1906) was kinder, dubbing Mackie’s composition ‘a good and competent rendering of a difficult subject, with nothing specially novel or “irreconcilable” in the treatment’.6‘ “Independent” art’, The Times, 10 Feb. 1906, p. 6. Reproducing Musical moments in The Studio (1906), E. G. Halton felt that Mackie ‘has successfully mastered the difficulties of lighting and composition which the subject presents’.7E. G. Halton, ‘Independent British art at Messrs. Agnew’s’, The Studio, vol. 37, no. 155, Feb. 1906, p. 30. Musical moments was reproduced here on page 24, with the French title Les Moments musicaux. Dubbing it a ‘large, skilfully lighted interior’, the English critic Laurence Housman argued that

the heads of the three principal figures are ranged too much in a straight line and at equal intervals, and the foremost figure is the least interesting in treatment: but the more distant figures are capitally arranged, and the sun-suffused shadows and peeping lights of the far-receding room make a charming pattern on the face.8Laurence Housman, ‘Independent painters exhibition’, The Manchester Guardian, 12 Feb. 1906, p. 4.

The painter and critic Bernhard Sickert, brother of the renowned artist Walter Richard Sickert, displayed clear prejudice against the northern artists in his review of the Agnew’s exhibition, declaring that ‘the Scotch element, though numerous, is distinctly weak’ and that

Mr Mackie’s Musical Moments is a very able piece of work in a style that is already old-fashioned, that of 1885, or thereabouts, when Mr. Sargent was our god.9Bernhard Sickert, ‘Independent art of to-day’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 8, no 36, Mar. 1906, p. 384.

Analysing Mackie’s work in 1908, the Scottish art historian James L. Caw felt that

in interiors with figures like ‘Musical Moments’ … he has shown an increased tendency to rely on his instincts, and a disposition to express his personal and immediate impressions of reality.10 James L. Caw, Scottish Painting Past and Present 1620–1908, T. C. & E. C. Jack, Edinburgh, 1908, p. 424.

Caw here came close to divining Mackie’s own feelings concerning Musical moments, expressed in a letter of 1906 to an art dealer friend in San Francisco, Frederic Cheever Torrey:

I am awfully glad and not awfully surprised to find that you liked my ‘Musical Moments’. One has only to read your type-written ‘Confessio fidei’ to expect you not to miss a thing done in earnest and with as little confusion in statement as possible. Everything in that picture was meant and the feeling of music in saturated light is a very recurrent one with me.11 Charles H. Mackie to Frederic Cheever Torrey, 14 Mar. 1906. Transcript of a letter held in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; copy in artist file, National Gallery of Victoria, courtesy of Bill Mackie.

The narrative of Musical moments, a spatially complex work, is divided into four distinct zones: a young violinist seated in the left foreground; an older pianist, seated, and a balding violinist, standing in the middle centre of the composition; a youngish couple engaged in earnest conversation at the far right; and two other figures, a moustachioed male and a female in an elegant hat and veil, seen in contemplative silhouette in the far left background. Added to this cast is a plethora of finely observed objects, from musical instruments, jewellery and items of dress, to a detailed sheet music stand, framed artwork on the wall and two goldfish in a glass bowl in the window recess at the far left. None of the characters depicted, apart from the couple at far right, engage with one another, although the younger and older violinists look straight out at the viewer. The painting seems to depict an interlude of rest between music rehearsals, rather than the musical moments alluded to in its title.

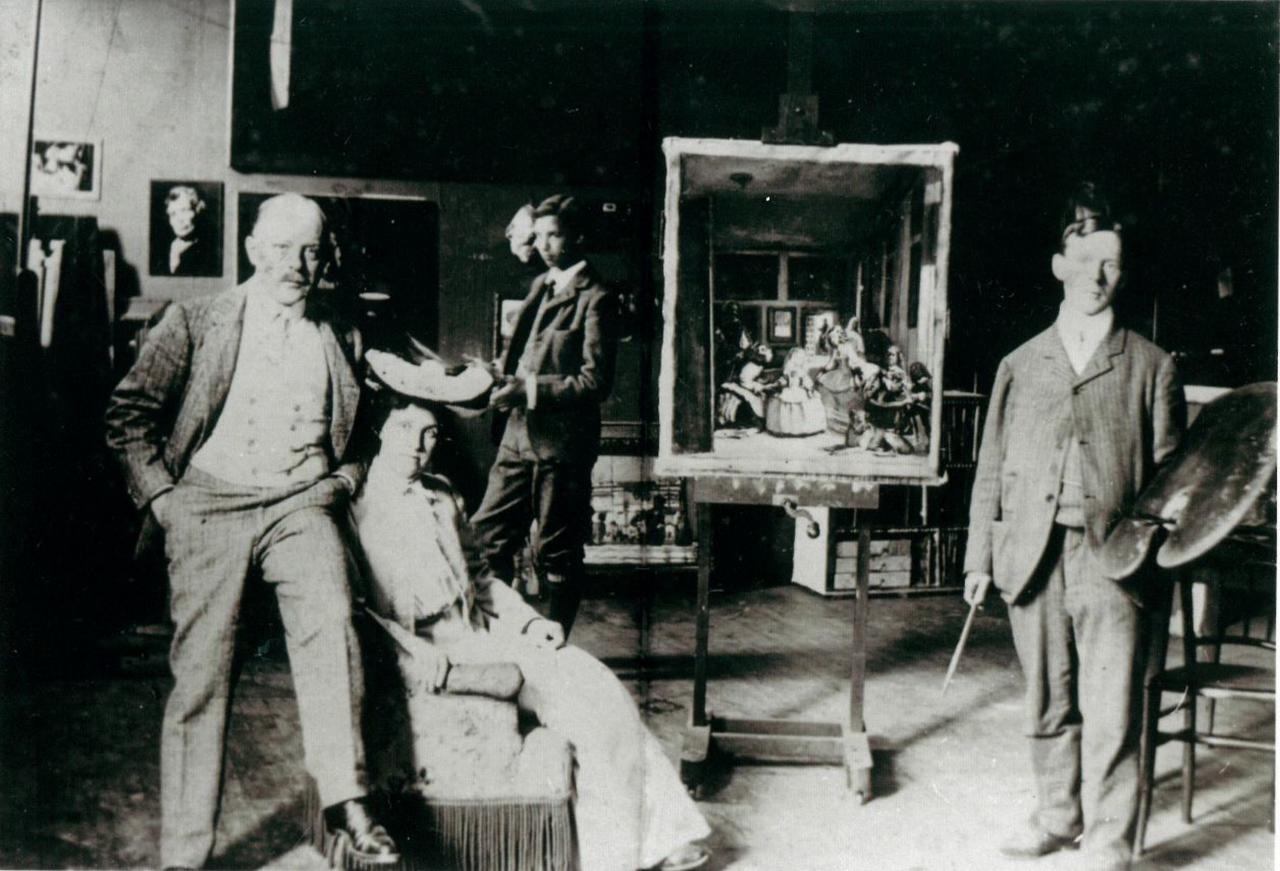

It has been noted that this work’s French title, Les Moments musicaux, given to it when it was reproduced in The Studio in 1906, references Franz Schubert’s Six moments musicaux, six pieces for solo piano published in 1828.12Pat Clark, p. 119. The narrative and spatial complexities of Mackie’s composition, as well as his bravura manipulation of subtle lighting effects across all its elements, seem surely to reflect his study of Velázquez’s Las Meninas,in 1904. A photograph taken in his brother William’s Paris apartment in mid 1904 shows Mackie standing proudly, paint brush and palette in hand, next to his Las Meninas copy placed on an easel.

The identity of the models who posed for Musical moments remained unknown when biographer Pat Clark published her monograph on Mackie in 2016. Subsequently, she was able to identify the young girl with the violin as Mary Elizabeth Waddell, known as Maimie, daughter of William Waddell, a teacher of music in Edinburgh and his wife Patricia Jessie Macnee, who are doubtless the pianist and balding violinist gathered at the piano in the middle distance.13Pat Clark, email to Bill Mackie and Ted Gott, 7 Mar. 2017; copy in artist file, National Gallery of Victoria. William Waddell had opened a violin school in Princes Street, Edinburgh in the late 1870s, which was carried on by his daughters Maimie and Ruth after his death.14National Library of Scotland, Papers of the Waddell School of Music, Edinburgh, acc. 12190, May 2006, <www.nls.uk/catalogues/online/cnmi/inventories/acc12190.pdf>, accessed 15 Mar. 2019.

Ted Gott, Senior Curator, International Art, National Gallery of Victoria