I wonder how many people have heard of Senka Taniguchi, or Fumie Taniguchi. Senka (meaning hermit’s flowers) was her pseudonym; Fumie was her real name. Feted during the 1930s, Taniguchi was seen as the seminal artist of her time. The art-loving public enthusiastically received anything she exhibited, and her popularity continued even after she left Tokyo’s acclaimed Seiryūsha Artists’ Association.

After marrying artist Funada Gyokuju (1912–1991) towards the end of the Second World War, she left Tokyo for his hometown of Kure City, Hiroshima, where they lived for ten years. In 1955 she migrated to the USA, where she remained until her death in 2001. She has largely been forgotten by the art world.

I first came across Taniguchi in a private art collection in 2010, where one of her works, Shunpū fujo (Woman in the spring wind), was on display. Viewing the painting was an emotional experience. The work was based on the traditional style of Japanese bijin-ga (paintings of beautiful women), a genre of Nihonga,1 Strictly speaking, Nihonga is painting produced after the Meiji Era, but it was also a technique used before that time. Nihonga painting used iwa-enogu mineral pigment crushed into powder. yet was imbued with a modernity and flair through the incorporation of subtle refinements. The work looked so modern that it was hard to believe it was produced during the prewar period.

I wanted to know more about this incredibly talented artist, but there was very little information available about her. Her own children had been unaware of her migration to the United States. It was not until 2011, when the Kure Municipal Museum of Art displayed her work at the Hiroshima, Lineage of Nihonga exhibition that I started to gather information about her. With the assistance of her children and art scholars, I have, over time, pieced her life together and located many of her paintings.

EARLY LIFE

Fumie Taniguchi was born in Tokyo on 2 August 1910 (Meiji 43), the second daughter of five children. Her father, Tokujiro Taniguchi, was the head of the Photographic Division of Asahi Newspapers, and in 1955 he was awarded the Photographic Association Prize. As a young artist, he had been involved with the Hakuba-kai, an artists’ society that produced European-style paintings. Taniguchi’s mother, Sei, came from a family that owned a Japanese kimono and fabric shop in Kyoto. An intelligent and stylish woman, she had studied Nihonga under accomplished female artist Uemura Shōen (1875–1949). Taniguchi’s paternal great-grandfather, Aizan Taniguchi (1816–1899), was a well-known scholar and artist, and is remembered as a patriarch of Kyoto art between the end of the Edo and early Meiji periods (late nineteenth century). Taniguchi was nurtured by her artistically talented family.

After the devastation of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, Taniguchi moved to Urawa in Saitama Prefecture. From this semi-rural area she commuted to Tokyo, enjoying the stark contrast between the two environments. This was a period of great artistic growth during which she began to develop her distinctive style.

After graduating from high school, Taniguchi studied Nihonga at the Women’s School of Fine Arts (now Joshibi University of Art and Design).In 1928, under her real name, Fumie Taniguchi, she entered a painting into an open competition at a Women’s School of Fine Arts exhibition; the work was selected.2 Information regarding Fumie Taniguchi’s works in the Women’s School of Fine Arts exhibition was sourced from Megumi Kitahara, Osaka University and You Ōuchi. The judging panel consisted of masters of Nihonga painting, including famed artist Ryūshi Kawabata, who became Taniguchi’s great mentor for the next decade. The exhibition was organised by Jitsugyo no nihon-sha, publisher of Fujin Sekai (Women’s World) magazine. The award was highly prestigious, and considered an essential stepping stone for female artists wanting to gain public recognition.

Taniguchi was a founding member of a graduate artists group, Aogaki-sha, formed in 1932 in the Nihonga faculty of the Women’s School of Fine Arts. At the group’s first exhibition, her work Kibi minoru (Sugar cane harvesting) received a great deal of interest from critics. Most of the exhibiting artists came from middle-class backgrounds, lived at home and had not been exposed to the ‘real world’. Taniguchi, on the other hand, had been exposed to working-class people from an early age. Critics remarked that her work captured a bold energy that seemed to radiate from the painting.

The following year, Taniguchi joined the Seiryūsha Artists’ Association, under the leadership of her mentor Ryūshi Kawabata, to exhibit her work. This became the base for her artistic career. As her practice developed, she began to focus primarily on working women as her subjects.

AT SEIRYŪSHA AND INDEPENDENCE

Taniguchi started to gain recognition after two of her works were entered into the 6th Seiryūsha Exhibition in 1934. The paintings depicted three joyful young women promenading along the street – an extreme departure for Taniguchi. The style of this work is more sophisticated than that of Taniguchi’s earlier works, and her interest in modern city life and the lives of the young women of Tokyo is clear. The setting of the fashionable district of Ginza, combined with these vibrant women parading their stylish, light-coloured clothes along the street, has resonances with a photogravure from a modern fashion magazine.

Taniguchi entered her work into every spring exhibition at Seiryūsha until she left the association in 1938. Her entries in the 1935 spring exhibition received mixed reviews from critics. Jikken-shitsu (Laboratory room) shows a female scientist handling test tubes. At the time, the concept of a female scientist was unthinkable; science was seen as the domain of men, and to infer anything different was unacceptable. The general view at that time was that female artists should depict only traditionally feminine activities in their art. The work was received poorly. Obi (Kimono waist sash), on the other hand, was reviewed favourably by the same critics, who admired the yellow obi against the red-coloured background and the sinuous, curved female figure wearing a kimono.3 Megumi Kitahara, ‘Japanese Painter, Taniguchi Fumie, Living in both “Modern” and “Tradition” (1910–2001)’, Departmental Bulletin Research Paper, vol. 48, Osaka University, 2014, pp. 1–25. Ryūshi Kawabata said that it exemplified and embodied Taniguchi’s whole artistic being, and Taniguchi herself said that Obi was her favourite work. I believe that Obi will come to be recognised as her greatest masterpiece, as it incorporates the best of all her characteristic styles and techniques.

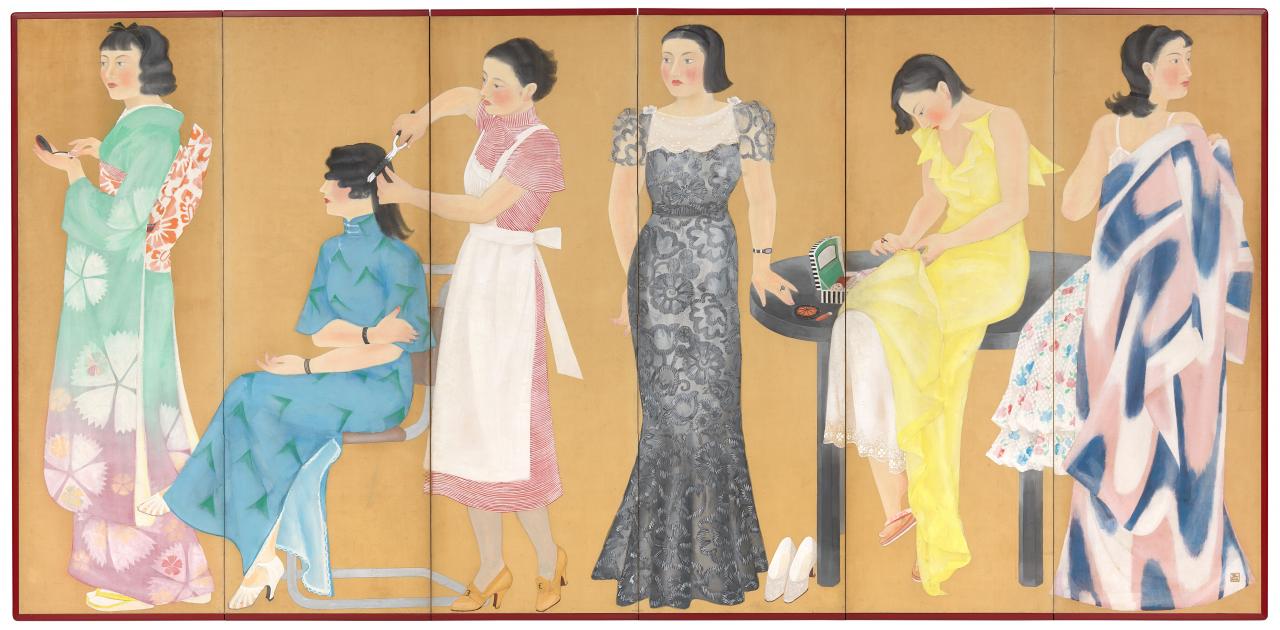

For the 1935 autumn exhibition at Seiryūsha, Taniguchi entered her work Preparing to go out (Yosoou hitobito), 1935, and received the prestigious Y-Shi Prize, which brought her fame in the Japanese art world. It also received harsh criticism in some circles due to its depiction of ‘modern’ girls. It is thought that the painting was inspired by the famous work from the Edo period Fujyo yūraku – zu Byōbu, c. 1600–1700 (Museum Yamato Bunkakan, Nara) better known as the Matsuura Screens, by Iwasa Matabei.

In Preparing to go out (Yosoou hitobito), which is now in the NGV Collection, Taniguchi has depicted a backstage-like dressing room scene, revealing activities that would not normally have been visible to the general public. The artist skilfully leaves the viewer with an impression that these are confident women preparing costumes with grace and refinement. She has delicately balanced various costumes and colours worn by the different performers and has reflected the fashions of the time. On the far left, one of the women uses a powder compact, and a lipstick rests on the table; these items were likely imported into Japan. The woman dressed in a Chinese costume is having her hair set into a permanent wave and wears nail polish and bracelets. The woman in the black lace dress wears a wristwatch that would be the envy of all women. The woman in yellow is repairing her Western-style dress while still wearing Japanese zouri (Japanese sandals for wearing with the kimono). The artist has cheekily included glimpses of white silk and lace undergarments. Preparing to go out (Yosoou hitobito) uses its subject as a metaphor for the arrival of a new age for Japanese women. In fact, these modern women can be interpreted as Taniguchi herself.

At the 1936 Seiryūsha exhibition Taniguchi again was awarded the Y-Shi Prize for her paintings of contemporary women. While her works continued to receive positive recognition from the art world, Taniguchi was the subject of some very pointed criticism. Women were increasingly accepted as professional artists by their male counterparts, but within designated boundaries. Some critics did not appreciate Taniguchi’s portrayal of modern young women wearing colourful Western clothes. They believed that she was being sensationalist and courting publicity for female artists – a very shallow motive, in their opinion. In reality, she was depicting important social changes that were occurring at that moment. She painted confident, sophisticated young women who, in the face of a conservative society, had the determination and courage to dress as they wished. Such women were sometimes subjected to ridicule, and even bullying.

With her success, Taniguchi was under great pressure to come up with works, new subjects and new techniques, which created stress and took a toll on her health. We can gain a better understanding of Taniguchi’s life in the Seiryūsha group and her inner thoughts through the stories she published many years later, after her move to the US. Taniguchi’s fictional work Tōyōki was published in 1974 (Showa 49) under her pen name Yoko Kazuki. In the story, the protagonist, Shino (believed to be based on Taniguchi), joins a school founded by Ryūshi Kawabata. Ryūshi exerts a lot of effort to teach Shino, and soon starts to develop great affection for her, treating her better than his own daughter, most likely because he sees she has the talent and imagination to become an eminent artist. With his guidance and support, Shino becomes the darling of the art fraternity, and there is an expectation that she will produce masterpiece after masterpiece. Initially, she finds these high expectations stimulating, but the ongoing pressure starts to take a heavy toll on her. This is made even more intolerable by Ryūshi who, seeing her success, demands even more of her. In the end, Shino cannot take the relentless pressure anymore, so there is no option for her but to leave Seiryūsha. Taniguchi herself left Seiryūsha in the late 1930s.

Taniguchi went on to join a new association of eminent young artists, Seishōkai, formed by art dealer Chōjirō Seki. Seishōkai opened its first exhibition in Tokyo during February 1938, before moving to Kyoto in March that year. Taniguchi gained the most attention of any of exhibiting artists. Aki no musume (A young woman in autumn) showed a sophisticated young woman wearing sporty, Western-style clothes, while Fuyu no musume (A young woman in winter) was a dynamic composition using monochromatic colour and depicting a vibrant modern girl wearing a kimono. Even though Taniguchi’s works attracted much attention and favourable reviews from the critics, not everyone was pleased with her success. She was the only woman artist in the group, and the other eleven young, ambitious male artists felt that she had received attention at their expense. There were also rumours that Taniguchi was having an affair with member Funada Gyokuju, reportedly the least talented in the group. This created friction, to which Seishōkai’s subsequent failure has been attributed.

Given her obsession from an early age with becoming a successful artist, Taniguchi had never given much thought to marriage. This had resulted in her missing out on developing the traditional skills of Japanese women like flower-arranging, tea ceremony and cooking. In Tōyōki, her character Shino expresses regret about missing out on these skills, admitting she was, perhaps, not fully prepared for a marital role.

Taniguchi had started a new life with Funada Gyokuju, who was beginning to show talent as a semi-abstract artist. Her decision to leave Seiryūsha may have been because of the intolerable stress she endured as a result of unrealistic expectations from the public and Ryūshi, institutional sexism and the vicious rumours spread by her peers.

After her departure from Seiryūsha, Taniguchi held her first solo exhibition, at the prestigious Kinokuniya Gallery in Ginza, in 1939. The exhibition targeted the art market, and drew a great deal of attention and mixed reviews. One critic thought her works were all masterpieces and displayed a unique style that could only have been created by a female artist. Reviews like this encouraged Taniguchi, and gave her the strength to continue to express her unique female viewpoint despite the backlash from the male establishment. Without the support of Ryūshi, however, her journey was going to be much more difficult. The negative reviews caused her to doubt herself and question whether she had the talent to succeed, but to her credit, she continued; she felt she had nothing to lose. To mark this new chapter in her life, she changed her name from Fumie Taniguchi to Senka Taniguchi.

Taniguchi started to actively display her works in major exhibitions such as the Rekitei Bijutsu Kyokai exhibition, the Kenkyūkai exhibition and the Bijutsu Bunka Kyōkai exhibition. In 1940, she opened her second solo exhibition at Ginza’s famed Shiseido Gallery. Her works, six large paintings created in the bijin-ga style, were all well received. Taniguchi had previously considered the paintings by her mother’s mentor, Uemura Shōen, to be old-fashioned, but now she understood and greatly admired them. It was at this time in her career that Taniguchi realised that female artists must represent a female viewpoint, otherwise their unique gender expression would be lost to the art world.

Taniguchi had been working hard to become recognised as an artist while also being a partner to Gyokuju. She learnt how to manage all that was expected of her, proving that a woman could fulfil her domestic role as well as forge an independent, successful career for herself – a confronting notion for males at that time.

TANIGUCHI AND HER ASSOCIATES

During the early 1940s Taniguchi displayed great dedication to creating new works, experimenting with styles and showing work in numerous exhibitions. In 1943, Jyoryū Bijutsu-ka Hōkō-tai (Dedicated Working Women Artists Group)4 The Dedicated Working Women Artists Group was led by the communication department of the Japanese Army. There was a total of fifty women members. The artists focused on war painting, which was designed to encourage mothers to ‘give away’ their boys to fight for Japan. was formed by the Army Communication Department and Taniguchi was appointed one of the committee members. The group held exhibitions of kenō-ga (paintings of dedication) by women artists, primarily aimed at supporting the war effort. One, in particular, was to support a major campaign called ‘sending your children and your students to war’. The members of the group also collaborated on paintings based on the theme of jyūgo (laying down arms). In addition to organising these art exhibitions, the women also supported the war effort by taking on jobs such as factory work.

TANIGUCHI’S LIFE IN KURE

Due to the severity of bombing attacks in Tokyo, Taniguchi and Gyokuju, now married, decided to move to Kure City, an hour from Gyokuju’s hometown of Hiroshima. Taniguchi gave birth to their eldest son at the Kure Naval Hospital in August 1945. The following year, she exhibited her work at a public artists’ exhibition and received the Hiroshima governor’s prize for work in a public exhibition.

Gyokuju started an art school and Taniguchi became his teaching assistant after the birth of their second son in 1947. Gyokuju did not charge fees to students who were genuinely studying Nihonga at his school, contributing to the couple’s financial struggles. Taniguchi earned additional income by accepting illustration commissions from newspapers and magazines, as well as selling some of her paintings.

The painting Sakura bijin-zu (Cherry blossom and a beautiful woman) is a collaborative work by Taniguchi and Gyokuju, and is believed to have been completed during this time. It is thought that Taniguchi painted the female figure, and Gyokuju filled in the background with thousands of fallen blossom petals. This is the only known painting they worked on together as husband and wife and, judging by the beautiful result, they must have enjoyed the experience.

In 1953, Taniguchi’s work graced the cover of the first edition of Nyonin Bungei, a magazine that published literary works by female authors. It was about this time that the relationship between Taniguchi and Gyokuju became strained. Taniguchi was finding it increasingly difficult to balance her role as a professional artist with those of wife and mother. Gyokuju was developing a reputation as an ambitious young artist with a bright future. Taniguchi believed he was so talented that he had a real opportunity to influence the future direction of Japanese art, but

she felt that this would only happen if they moved to Tokyo. This move would also allow her to resume her study and further her own career. Gyokuju was against moving and wanted to continue as the head of his local art group in Kure. A major rift started to develop between them. Gyokuju became involved with another woman and began to spend more and more time away from Taniguchi and their two young children, sometimes not returning home for days.

Eventually, Taniguchi felt that she and the children had little choice but to leave Gyokuju, so they travelled back to her hometown of Saitama, where her parents lived. Her parents, who had been well-off before the war, were now old and impoverished and, much to her dismay, Taniguchi found that she and her the children were not welcome in their home. Even her artist friends in Tokyo, who once welcomed and spoiled her, turned their backs on her. To make a living, Taniguchi wanted to open an art school at her parents’ house, but they wouldn’t allow it. Sadly, without the means to make a living, she had no choice but to take her children back to Gyokuju in Kure. Her eldest son Fujio recalls his mother’s words when she brought them back to the family home: ‘You and your brother need to cross the bridge that leads to the house and run to the entrance where your new mother is waiting for you; once you have crossed you can never look back’. That evening, Taniguchi stayed with a friend in Kure and was so distraught that she cried all night. The next day she returned to Saitama, alone.

RE-ESTABLISHING HER LIFE

At her parents’ home in Saitama, Taniguchi buried herself in her work to mask the pain of her loss. She entered work into the Fourth Saitama Art Exhibition in 1953. In November 1954, she opened a solo exhibition at the Kobaruto Gallery in Urawa. At the same time, the renowned avant-garde woodblock artist / photographer Ei-Q wrote a very favourable critique of her work. In a diary left at Kobaruto Gallery, Taniguchi described her desire to leave the conventions of Nihonga painting behind and develop a new artistic expression based on abstraction. She worked tirelessly to realise her ambition to become a well-known professional artist in Tokyo. She continued creating Nihonga works, but also broadened her practice to include abstract painting, fabric dye-craft, and suiboku-ga (sumi-e) brush and ink painting.

No matter how much time and effort she poured into her art, however, her children were always in her thoughts. One day she had the chance to meet her two sons in Hiroshima after getting permission from Gyokuju. After hearing that they were happy with their new mother, she decided that it was in their best interests that she not upset this relationship by forcing her way back into their lives. In a letter to a friend, Taniguchi confided that she was satisfied to know that the two children were happy and well looked after. We can only guess the true extent of the emotional trauma and pain that she endured for the sake of her children.

The trauma of losing her children was not the only challenge Taniguchi faced during this period. She continued to battle for acceptance in the male-dominated art world of Tokyo, while struggling to support herself financially. She was in a desperate state and saw little hope for her future; she wanted to escape from this agonising situation. Therefore, when Japanese-American man Charles Juzō Umemura asked her to marry him and move to the United States with him, it seemed like the answer to all of her problems. She accepted his proposal and looked forward to starting her new life and second marriage in the USA.

In an interview that took place before she migrated to the United States, Taniguchi discussed her plans to introduce Japanese Nihonga to the art-loving public of the USA and, one day, having her children join her there. She left Yokohama by ship for California, making a transit stop in Hawaii, where she produced some detailed and colourful landscape sketches, then travelling on to Salt Lake City, Utah.

Taniguchi gave the impression that she enjoyed her first Christmas in Salt Lake City, of which she made a few drawings, and was glad to be there, but in reality her marriage was not a happy one. Although of Japanese heritage, her husband looked down on Japanese people and their culture, taking every opportunity to boast about how he had rescued a poor Japanese woman from poverty and brought her to the USA. The marriage only lasted two years.

After divorcing Umemura, Taniguchi supported herself by working as a waitress, a live-in housekeeper and a seamstress; she also studied English at a language school. She met her final partner, Kenji Nukaya, an American-born gardener who suffered ill health. Taniguchi was attracted to his unconventional nature, and he was able to provide her with honest feedback and encouragement within a stable, happy home environment. In a letter addressed to Gyokuju’s sister Mui Masuki, Taniguchi wrote: ‘Perhaps I have never experienced such happy and relaxed days in all my life’. Eventually, she was able to write openly about those difficult times in Japan and published her story in the journal Nanka Bungei.

Taniguchi made several visits to Japan but never lived there again. She had contemplated returning to Japan via Europe because she thought her art would be well received there, but she never went. According to Taniguchi’s niece, Taniguchi stayed in the USA because she could not face living in Japan without her children.

She looked after Kenji for the remainder of his life and, after his death, she moved into a special facility for elderly Japanese-Americans in Los Angeles. She remained proud of her Japanese heritage, often singing Japanese songs and giving informative talks to visitors to the facility. In 2000, she played the minor role of a Japanese woman in a kimono in the movie Bubble Boy. Taniguchi died at the age of 91, in 2001.

In August 2008, three Buddhist paintings (butsu-ga) by Taniguchi were loaned and subsequently bequeathed to the Kōyasan Buddhist Temple in Los Angeles at a memorial service commemorating those killed by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs. One of the paintings shows a smiling heavenly female messenger in the centre holding a child and surrounded by animals. Two Bodhisattva paintings were displayed on either side of it.5 A Bodhisattva is someone who is on the path to becoming a Buddha. Perhaps the messenger was a subconscious representation of herself, a mother separated from her children.

TANIGUCHI’S PAINTINGS RETURN TO HER HOMELAND

As a result of renewed public interest and research into Taniguchi’s work in recent years, many of her artworks have been rediscovered and returned to her family.

Before leaving Japan for the USA, Taniguchi had asked her friends to look after her works. Although many of these friends and their immediate families had already passed away by the time Taniguchi died in 2001, their descendants had retained the works. By chance, a work was discovered in Kure City in January 2012, and the discovery was reported in a newspaper. On reading this article, Taniguchi’s own descendants wanted to know more about her life, and what happened to her in the USA. They were able to find out where Taniguchi had lived and eventually located many of her works. A subsequent exhibition at Kure Municipal Museum of Art displayed more than 130 of them.

Taniguchi persevered with her passion for art despite the dreadful turmoil of war, the chauvinistic barriers that inhibited female artists, the trauma and pain of separation from her children, and the sense of dislocation caused by her move to the USA. Her career is a testament to her dedication to creativity and her ability to deal with the challenges faced by women during the twentieth century.6 Information regarding Fumie Taniguchi’s works of art produced prior to the Second World War were sourced from Taniguchi’s first son Fujio Funada; Kana Kobayashi, Chugoku Newspaper; and Megumi Kitahara, Osaka University. Megumi Kitahara’s extensive work on the subject has been central the research of Taniguchi Fumie’s career. The editors would also like to acknowledge Takako Routledge for the translation of this essay and Wayne Crothers, Senior Curator, Asian Art at the NGV, for his assistance in facilitating this submission and for his review.

Notes

Strictly speaking, Nihonga is painting produced after the Meiji Era, but it was also a technique used before that time. Nihonga painting used iwa-enogu mineral pigment crushed into powder.

Information regarding Fumie Taniguchi’s works in the Women’s School of Fine Arts exhibition was sourced from Megumi Kitahara, Osaka University and You Ōuchi.

The Dedicated Working Women Artists Group was led by the communication department of the Japanese Army. There was a total of fifty women members. The artists focused on war painting, which was designed to encourage mothers to ‘give away’ their boys to fight for Japan.

A Bodhisattva is someone who is on the path to becoming a Buddha.

Information regarding Fumie Taniguchi’s works of art produced prior to the Second World War were sourced from Taniguchi’s first son Fujio Funada; Kana Kobayashi, Chugoku Newspaper; and Megumi Kitahara, Osaka University. Megumi Kitahara’s extensive work on the subject has been central the research of Taniguchi Fumie’s career. The editors would also like to acknowledge Takako Routledge for the translation of this essay and Wayne Crothers, Senior Curator, Asian Art at the NGV, for his assistance in facilitating this submission and for his review.