Art can save you. Art can change you. Art is an act of power. Don’t let anyone say you can’t do it or say otherwise. I think if I could inspire other people or have other people talk about my work in the future, I just want them to remember that I am just this kid that came from the west. I had nothing and took a chance.

Reko Rennie, 2024

In 1984, when Kamilaroi artist Reko Rennie was just ten years old, he made his way to an old, dilapidated building at the back of his primary school with a stolen can of spray paint. He proceeded to paint his name, ‘REKO’, in all caps on the back wall of the building. This was his first tag – the identifying mark of a graffiti artist – in what would become a career in graffiti that would ultimately change his life forever.

Growing up in the multicultural western suburbs of Melbourne, Rennie recalls that racism wasn’t an issue for him. Those experiences would come later. As a child, his friendship circles were marked by their cultural diversity. ‘I was learning jiujitsu with a whole bunch of different European immigrants and nationalities, first-generation kids who were born here, but who all had parents from overseas,’ says Rennie. ‘There were Vietnamese immigrants, Hindu, Muslim, Jewish kids, all these different nationalities, a real melting pot of diversity in the community.’1 All quotes in this essay courtesy Reko Rennie, interview with the curator, August 2024.At its core, jiujitsu is about leveraging technique over strength and size, emphasising intellect and control as superior to brute force alone. As an art, it promotes mental discipline, humility and respect – qualities that have ultimately shaped Rennie’s character and career.

Primarily raised by his mum and paternal nan, Rennie considers both women major inspirations for his art practice today. His work particularly focuses on his late nanna Julia, a Kamilaroi/Gamilaraay woman who was born in Walgett, northern New South Wales. While Rennie’s mother worked long hours to care for her family, his nanna Julia, a member of the Stolen Generations, taught him about many of life’s lessons. As a little girl, Julia was taken from her family and forced to work as a cleaner and a cook on pastoral stations and Christian missions. Holding firm to her Christian beliefs and respect for the British monarchy, Rennie’s nanna remained a staunch and proud Aboriginal woman throughout a life that included the contradictions of trauma response.

Watching his nanna manoeuvre through colonial histories while staying rooted in her ancestral strength ignited something in Rennie, who became aware of the profound impacts of structural racism at a young age. Although racism was not a daily lived experience for Rennie as a child in the 1980s, he recognised its devastating effects on his inner-city community, which was often troubled by drugs and crime. Further, Rennie’s childhood was marked by poverty – his family’s financial circumstances were without a doubt linked to the structural racism experienced by generations before him. Rennie’s mother worked hard to keep food on the table, but like many Aboriginal families, their reality was vastly different from the Australian national identity being exported at the time.

In the 1980s, Australia was ‘the lucky country’, a masculine nation where the men were rugged and outdoorsy. Australian identity was synonymous with mateship and a laid-back attitude, epitomised by white surfer boys and outback-dwelling bushmen – also white. Through wildly popular figures like Paul Hogan and his character Crocodile Dundee, Australia cultivated an image of a wealthy, friendly and mostly white nation. Rennie’s experiences would continue to sit at odds with this version of Australian life, ultimately becoming the foundation for an art practice that would at its core challenge people to reconsider their understanding of modern Australia and Aboriginal contemporary art.

Rennie’s mother would find ways to inspire and encourage her son that didn’t involve spending money, such as visiting Melbourne’s cultural precincts, particularly Melbourne Museum, the Royal Botanic Gardens and the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV). The artist has strong memories of his visits to the NGV, where he was particularly inspired by the international art collections. Rennie would spend hours looking at the Asian art and memorising objects from the antiquities collection – he has something of a photographic memory and can still describe these works in great detail today. He recalls studying the gallery’s Buddhist deities, altars and statues, drawn to these objects in part because the dojo he was studying jiujitsu at was decorated with similar religious items. Despite his close relationship with his nanna, a devout Christian, Rennie rejected the notion of a singular white, male god. This scepticism towards organised religion was partly informed by Rennie’s diverse circle of friends, kids from various religious and non-religious backgrounds. As a teenager, none of the diverse philosophies Rennie encountered seemed capable of aligning with each other.

Aged eleven or twelve, Rennie created his first artwork, a distinctly colonial-looking landscape oil painting that he created in a community art class. It wasn’t until Rennie was a little older that he started seeking out art related to his Indigenous heritage. During this period, the NGV primarily collected works by Indigenous artists living ‘on Country’, including Arnhem Land bark paintings, Papunya composition boards and conceptual maps by desert artists. Rennie felt a noticeable disconnection between this type of Indigenous art and his own urban experience. The idea of ‘Dreaming in urban areas’, a phrase coined by Goenpul woman Lisa Bellear in her book of the same name, resonated with Rennie, having grown up in a concrete jungle. The concept later became synonymous with another Melbourne-based contemporary Indigenous artist, Destiny Deacon. Rennie continues to find inspiration in feminist art icons like Bellear and Deacon, among many others who motivate his artistic practice.

It was the feeling of disconnection between the Aboriginal art hanging in galleries, mainstream white Australian culture and Rennie’s lived urban experience that ultimately led him to graffiti. For the young Rennie, graffiti was synonymous with city life, so it held great emotional and cultural significance as an art form. He first started seeing graffiti as art after taking train trips to visit his other grandmother in Hampton, in Melbourne’s south-east. Along the train line he would see countless tags by identifiable but anonymous artists, and this inspired in him to embrace graffiti as a visual language of his own. It was the mid 1980s, and the films Breakdance and Beat Street had just come out. Set in the South Bronx, New York City, these American dance dramas highlight graffiti and hip-hop culture, and for Rennie, who was learning to breakdance at the time, seeing these films was a turning point. Around this time Rennie also found a book at the local library, Subway Art by Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant. The book was essentially one long photographic essay on the subculture of hip-hop, breakdancing, graffiti and DJing, mostly in the Bronx and the Lower East Side of New York. Inspired to create, Rennie and his friends began stealing spray cans and tagging inner-city Melbourne.

Around this time, the teenage Rennie changed schools, and for the first time found himself in predominantly white classrooms, where he encountered overt racism directed towards him on a daily basis. Despite this, he credits much of his enduring passion for graffiti to a network of fellow students from this time who shared his interest in the art form. Engaging with this community, in which many participants did not necessarily identify as artists, deeply influenced his perspective. Even after three decades, Rennie maintains connections with many of those artists he befriended as a youth, with several of them still actively tagging well into their fifties.

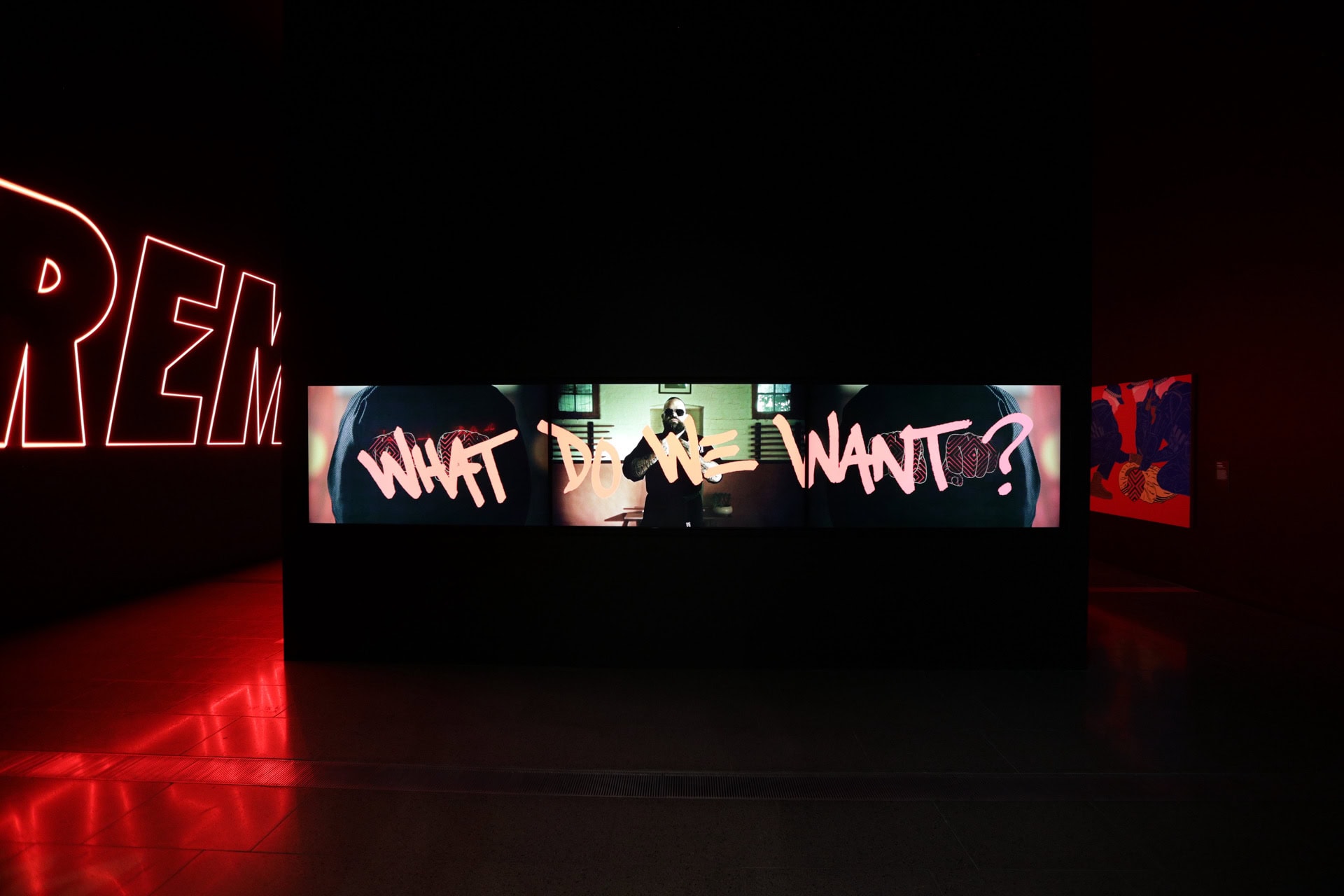

In the late 80s and early 90s, the stencil movement really began to take off within Melbourne’s graffiti scene. Stencilling involves creating intricate designs by cutting out shapes or patterns from materials like paper, acetate or cardboard, then applying paint through the stencil onto surfaces. This technique allows artists to quickly reproduce their work in various locations, often conveying social or political messages. The move from tagging and graffiti to stencilling occurred at the same time Rennie first began making deliberately political artwork. This work was defined by his commitment to social justice, particularly focusing on themes related to Aboriginal rights, land rights, trade unionism, Blak identity and the Stolen Generations. While Rennie officially stopped tagging and stencilling in 1995, when he was twenty-one, he still carries a sharpie or a texta for the occasional politically motivated tag.

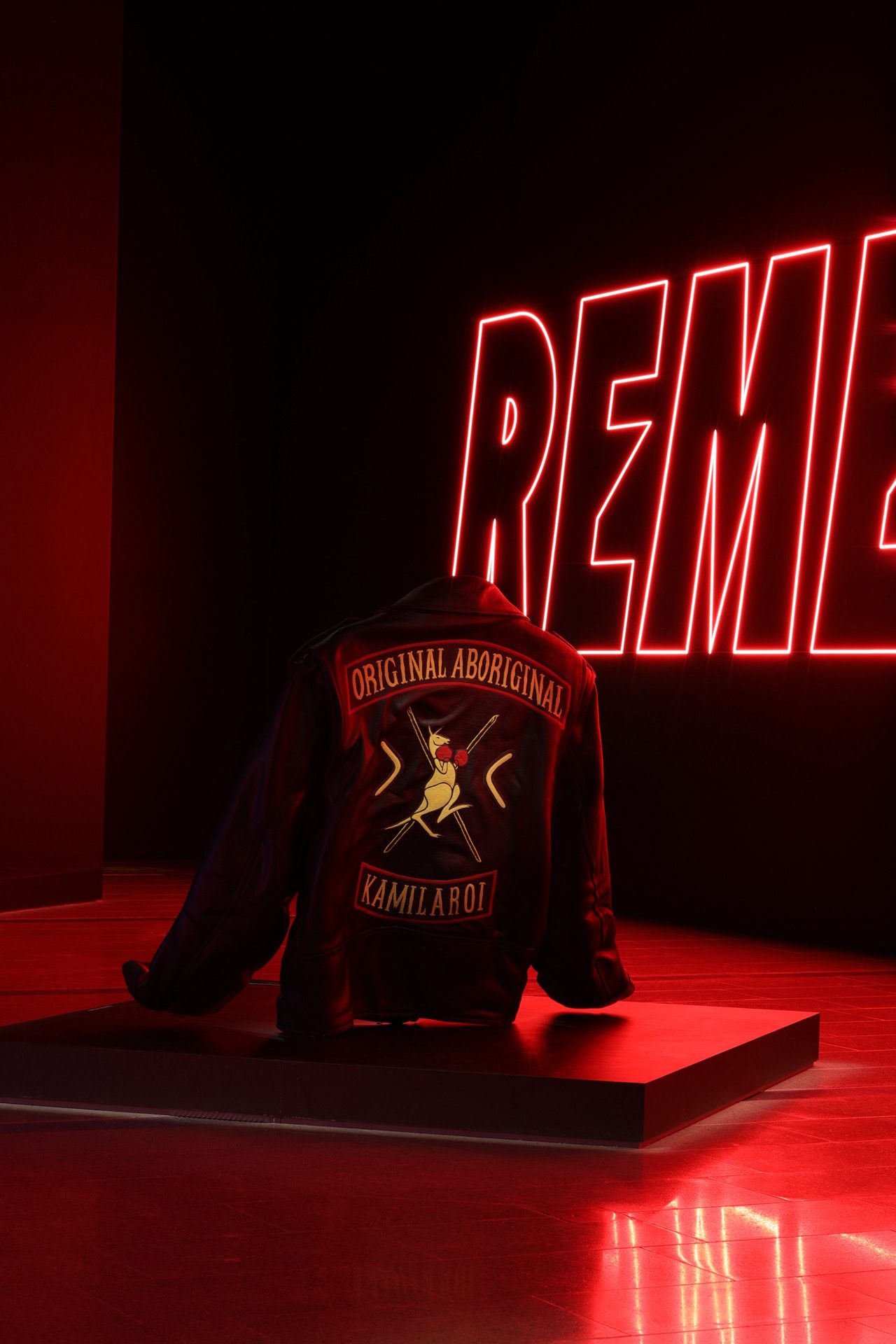

In his early graffiti days, Rennie painted surfaces with symbols like the Aboriginal flag, the crown, the skull and the letters INDIGI (shorthand for ‘Indigenous’) and OA. Standing for Original Aboriginal, OA was Rennie’s his first real pseudonym and became his debut signature in the world of tagging. Standing for Original Aboriginal, OA has continued to be a significant and recurring motif throughout Rennie’s work. Rennie carried a pink pastel marker from Japan that he would use to tag on the fly, sparking a creative fire within him that has seen his artistry evolve. His story echoes the experiences of many young artists of his time: kids who began tagging on the streets would gradually start making more ambitious works. Many of those artists, including Rennie, would then go on to secure significant mural commissions, and with leftover paint from paid projects, they’d continue to proliferate their own art.

From the 2000s onwards, Rennie began putting his work on canvas and entering awards. He never formally trained as an artist, so he would enter group shows as a way of refining his work. In 2008, Rennie won $10,000 in the fourth annual Victorian Indigenous Art Awards for his work Big Red at the Koorie Heritage Trust. Following this, Rennie developed a healthy confidence in his work and began to study art magazines, immersing himself in the international contemporary art world. Rennie would write down the details of curators, shows and galleries around the world, and every week he would send images of his work to collectors and curators, hoping for a response. His tenacity paid off when he became the first Aboriginal artist to become represented at the prominent independent gallery This Is No Fantasy. Rennie considers that to be a career-defining moment, as what followed was a residency at Cité Internationale des Artes. Rennie had been working multiple jobs up until this point, including as a journalist for the Age and as a correspondent at the Koori Mail. From 2009, however, Rennie dedicated himself to art full time. With little more than a credit card and the support of his family – particularly his then partner Eva Galvin – he embarked on a career as a full-time professional artist.

Visiting Europe was a key moment for Rennie, like so many other Australian artists before him. For Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Hugh Ramsay, Margaret Preston, Grace Cossington Smith, Albert Tucker and Sydney Nolan, just to name a few, the pilgrimage to Europe in the name of art was almost a rite of passage. While Rennie was deeply inspired by his time in Europe, it was American figures such as Andy Warhol, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat who would ultimately inspire him the most. Upon returning to Australia, Rennie took further inspiration from Australian-American sculptor Clement Meadmore and Australian sculptor Inge King, both known for their large-scale abstract sculptural works. Rennie became motivated to explore hard-edge abstraction and sculpture, with his art becoming characterised by fluid forms overlaid with bold, geometric patterns sculpturally rendered in hard-edge materials. His dynamic public sculptures can be found throughout the world and are immediately recognisable due to his signature aesthetic.

One recognisable characteristic of Rennie’s work is his vibrant use of colour. He continues to see his preference for bright colours not only as defiance against the hyper-masculinity prevalent in his upbringing but also as a rejection of the traditional use of ochre in Aboriginal art. In defiance of the stereotypes he encountered in his youth regarding how young Aboriginal artists ‘should’ make art, Rennie purposefully adopted a palette that departed from the expectations of Indigenous art. Rennie confronts the misconception that being ‘authentically’ Aboriginal means being at odds with modernity, recognising, like many Aboriginal people, the importance of actively shaping his identity amid historical stereotypes depicting Indigenous culture as static.

Beyond his use of colour, there are other symbols that have continued to appear throughout Rennie’s oeuvre: the crown, the diamond, the flag, the spray can and the skull. Each symbol can be interpreted in a multitude of ways. Take, for example, the Kamilaroi diamond, one of Rennie’s most utilised motifs, traditionally a men’s initiation symbol for Kamilaroi people. Rennie recalls learning from family members about how their ancestors built a sophisticated society defined by tolerance. In his work, the diamond is a way of asserting Rennie’s connection to culture, as well as a critique of what he sees as colonial Australia’s underlying misogyny, homophobia and classism.

Similarly, the crown that often features in Rennie’s art possesses multiple layers of significance. While influenced by Basquiat’s use of the crown, Rennie also recalls how, even before Basquiat, artists would paint a crown into their graffiti tags to assert their dominance and artistic prowess, signalling themselves as ‘the king’ or someone who is at the top of their game. On another level, the crown references Australia’s status as a monarchy, a concept that has bothered Rennie since he was a child. In part, Rennie’s critique of the monarchy comes due to his grandparents’ reverence for Queen Elizabeth II. ‘The monarchy was never the true royalty of Australia,’ emphasises the artist, ‘The continent has always been and will always be Aboriginal land.’ From a young age Rennie recognised the crown as a symbol of foreign rule over Indigenous land. For him, it serves as a reminder of the original royalty of Australia: the Senior women and men who held custodianship over the land for over 65,000 years before the British arrived.

Another recurring symbol in Rennie’s work is the skull, which the artist describes as being about survival. Today, Aboriginal people are often referred to as the most incarcerated peoples on the planet. Despite making up only 2 per cent of the general population, Aboriginal people represent 26 per cent of the prison population.2 Amnesty International, ‘The overrepresentation problem: First Nations kids are 26 times more likely to be incarcerated than their classmates,’ September 8, 2022. First Nations people in Australia are ten times more likely to be imprisoned during their lifetime and have a life expectancy rate that is estimated to be 8.6 years shorter for men and 7.8 years shorter for women.3 Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander life expectancy,’ November 29, 2023. Unequal access to housing, education and healthcare, along with the ongoing dispossession of traditional lands and the lived consequences that come from generations of inherited trauma, have created a massive gap in equality. All this is encompassed in the symbol of the skull. As Rennie says, ‘The skull is about life, it’s about the life we choose. The life we live, and the life we could have lived. It is life and death.’

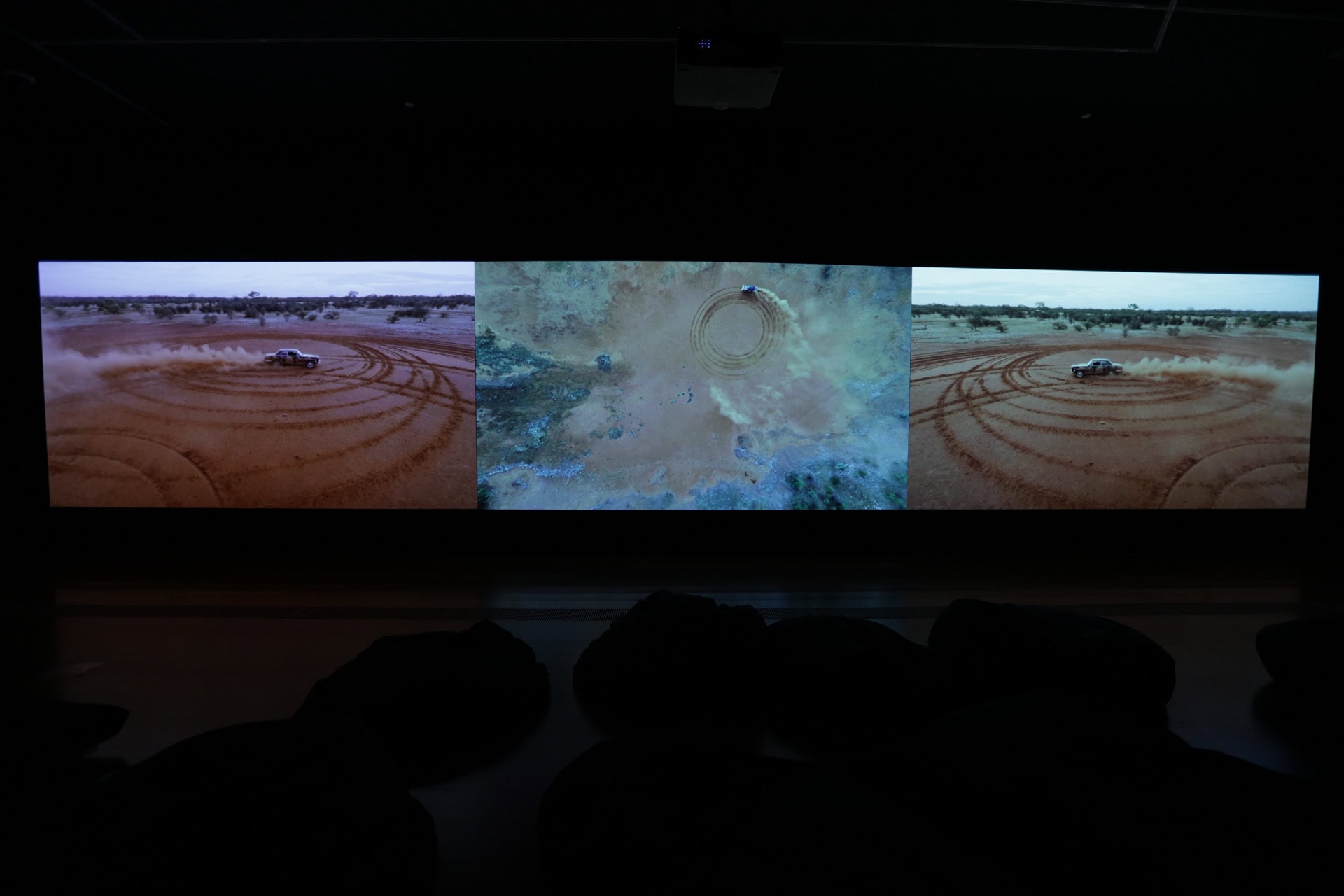

Since his formative years working on the street, Rennie has achieved remarkable success. His work has been acquired by major national and international institutions, he has secured numerous public art commissions, and his pieces have been showcased in prestigious international events such as the Venice Biennale. His work was even projected onto the sails of the Sydney Opera House, arguably one of the most prominent locations for any artist in Australia. Continuously evolving, Rennie now explores various mediums, including video, marble, bronze and installation, producing contemporary art that is exceptionally resolved, profoundly intelligent and daringly political.

Rennie’s art stands as a proclamation of Indigenous sovereignty. Drawing inspiration from his own life and ancestral connections, as well as his ongoing interest in international art, Rennie’s works challenge persisting and harmful racial stereotypes. As future generations encounter and contemplate Rennie’s contributions to contemporary art, they will come to understand that regardless of an artist’s background, art can serve as a powerful medium for expressing identity and pushing attitudes towards non-violence, acceptance and diversity, while nurturing a sense of empowerment.

Myles Russell-Cook is NGV Senior Curator, Australian and First Nations Art.

REKOSPECTIVE: The Art of Reko Rennie is on now at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia.

Notes

All quotes in this essay courtesy Reko Rennie, interview with the curator, August 2024.

Amnesty International, ‘The overrepresentation problem: First Nations kids are 26 times more likely to be incarcerated than their classmates,’ September 8, 2022.

Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander life expectancy,’ November 29, 2023.