Exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1887, The first cloud, 1887, is one of William Quiller Orchardson’s finest commentaries on the social life and manners of his time. When the NGV acquired this painting in 1887 Sir Henry Tate, one of Orchardson’s regular collectors, commissioned him to paint a replica for Tate’s own collection. This slightly smaller copy of The first cloud, which differs from the original in various details, is now at the Tate, London.1The first cloud,1887, oil on canvas, 83.2 x 121.3 cm, Tate Britain, London, presented by Sir Henry Tate, 1894 (No. 1520). In March 1894, the Melbourne newspaper The Argus had run a slightly inflammatory editorial on the subject of copies at the National Gallery of Victoria: ‘Original or replicas? The question is constantly agitating the minds of visitors to the Melbourne National Gallery, and a certain sense of disappointment comes from time to time with a discovery that some cherished favourite in the national collection is not the original picture’. The newspaper noted that ‘there are two “First Clouds”, of which we have the original’, Editorial, The Argus, 13 Mar. 1894, p. 4. In response to this editorial, the Gallery Director, L. Bernard Hall, reported that while a revised catalogue of the collections would shortly clarify matters in respect of a number of Melbourne’s copies or replicas: ‘There will be no occasion, however, to mention that another “First Cloud” exists, for I have a letter from Mr Tate admitting that his (a slightly smaller one) is a replica from the picture exhibited in the Royal Academy of 1887, now in our gallery, and not, as stated in the Magazine of Art for Sept. 1893, “the finished sketch” for the same’. L. Bernard Hall, ‘La Defenestration (To the Editor of The Argus)’, The Argus, 16 Mar. 1894, p. 7. Annette Dixon, former Curator, NGV, first sourced this reference.

Orchardson, a Scotsman who had trained in Edinburgh, moved to London in 1862. Here he made a name for himself as an elegant painter of anecdotal narratives and comedy-of-manner pictures set in eighteenth-century and Napoleonic-era surrounds. He paid careful attention to details of dress and interior design (his meticulousness is amply conveyed in The first cloud’s sumptuous, if chilly, decor).

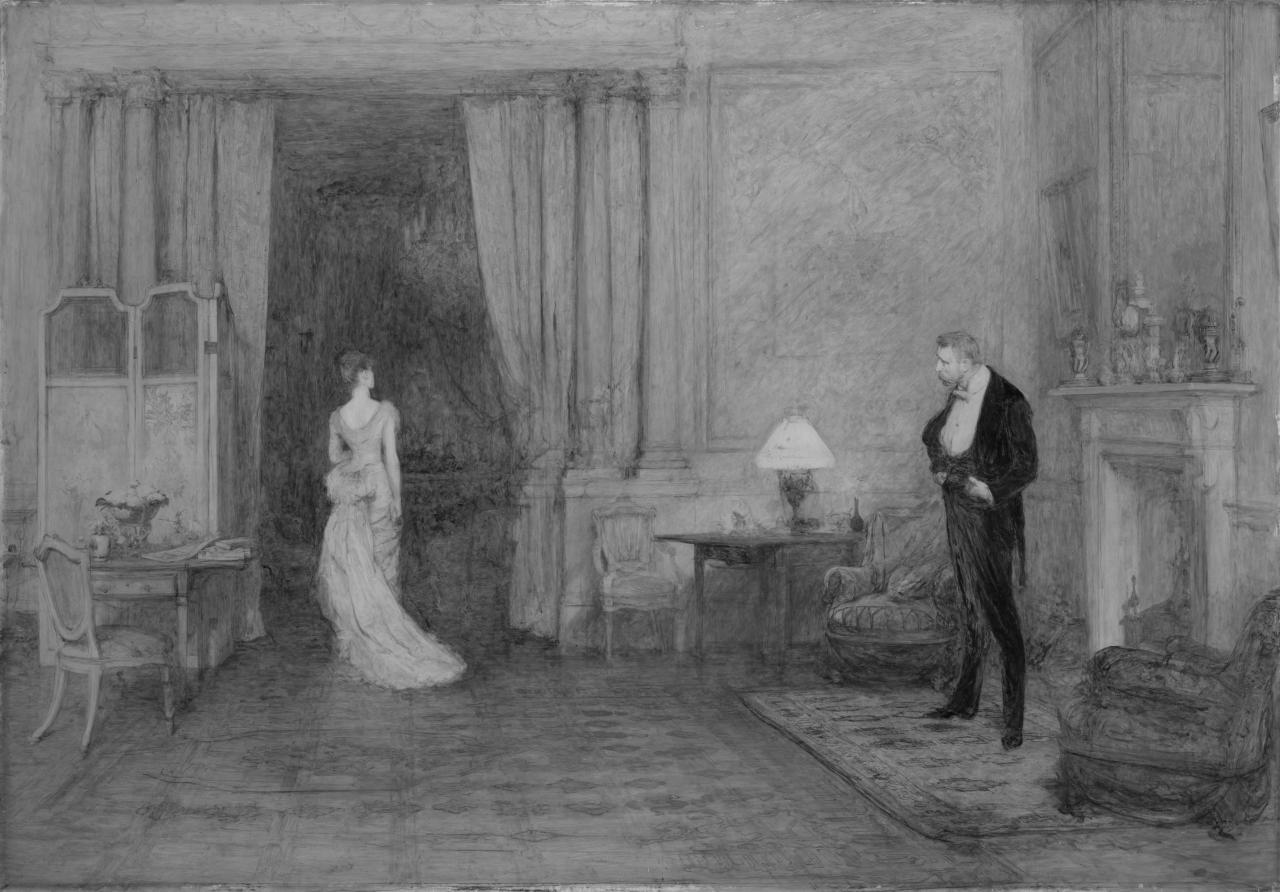

Among Orchardson’s first paintings to depict people in contemporary clothes, The first cloud shows a couple who have just returned from an evening out (they are elegantly dressed, but there is no fire in the grate). Their evening has turned sour, however. This was Orchardson’s third study of marital discord. He had previously exhibited Mariage de Convenance, 1883 (Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow), and Mariage de Convenance – After!, 1886 (Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums), both of which dealt with an extreme mismatch of age between a young bride and an elderly husband.

When shown at the Royal Academy, The first cloud was accompanied by two lines from the poem ‘Merlin and Vivien’ by Alfred Tennyson:

It is the little rift within the lute

That by-and-by will make the music mute2 Alfred Tennyson, ‘Merlin and Vivien’ from Idylls of the King, 1859. See Angus Trumble, Love and Death: Art in the Age of Queen Victoria, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2001, p. 136.

Taken together with the painting’s title, these lines seem to suggest that this cloud is but the first of many in a storm that threatens to overwhelm this marriage.

The painting’s drama was intently discussed upon The first cloud’s unveiling. The Art Journal (1887) wrote of how ‘the back of the retreating lady is most ominously suggestive of angry determination’.3‘The Royal Academy Exhibition’, The Art Journal, 1887, p. 248. While The Portfolio (1887) felt that Orchardson’s depiction of the frustrated husband, his hands thrust into his pockets in mute rage as his wife sweeps from the room, was ‘perhaps, the finest Mr Orchardson has painted [for its] contending emotions, the selfish anger which is just disappearing to leave room for a look not of shame exactly, but of apprehension lest he has gone too far for his own comfort’.4Walter Armstrong, ‘Scottish painters. X’, The Portfolio, vol. xviii, 1887, pp. 231–2.

In preparing this study of contemporary life in London, Orchardson may have been reflecting upon recent political developments that had considerably enhanced the status of women in Britain. Many of these reforms were ushered in by William Gladstone, leader of the progressive Liberal party, who in 1880 had won Britain’s general election for the second time. Gladstone’s government promised legislation that would address the legal inequalities that existed between men and women. The Married Women’s Property Act of 1882 now gave women the right to separately own property after marriage. Prior to this act, anything a woman owned had automatically become the property of her husband. It is intriguing to consider whether this legislation may have provided a topical subtext to the marital dispute depicted in The first cloud.

The painting was caricatured in Punch magazine on 7 May 1887, however, in a manner that interpreted the husband as being the triumphant party. Dressed as a painter, he was shown in Punch muttering to his wife’s back: ‘Yes, you can go; I’ve done with you, my dear. / Here comes the model for the following year. / (To himself) Luck in odd numbers — Anno Jubilee — / This is Divorce Court Series Number Three’. This may reflect entrenched social attitudes towards women in certain quarters at the time; although this is balanced by the Portfolio’s (1887) contemporaneous comment that in The first cloud ‘the fault is laid … on the man’.5ibid. p. 231.

Yet another perspective has been added by Norwegian literary scholar Toril Moi. Noting that Orchardson first exhibited The first cloud alongside poetry by Tennyson from ‘Merlin and Vivien’, in which the temptress Vivien ensnares the wizard Merlin, Moi argues that Orchardson ‘thus enables spectators to believe, without much hesitation, that the painting represented the first step towards the ultimate destruction of a marriage by female adultery’.6Toril Moi, Henrik Ibsen and the Birth of Modernism: Art, Theatre and Philosophy, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 2006, p. 134.

Examination of The first cloud with infra-red photography (below) reveals the careful manner in which Orchardson constructed this marriage drama. He originally drew in a floor that was totally covered by a patterned carpet. In the final painting, however, Orchardson removed this carpet, leaving the disgruntled husband stranded on a small oriental rug awash in a sea of wooden parquetry.

Orchardson was frequently daring in the way in which he painted open space and ‘emptiness’, allowing the viewer to better focus upon the social drama enacted in his compositions. The cold room and the almost bare parquetry floor of The first cloud offer a perfect setting for this frosty scene of marital discord. Writing in 1881, art critic Alice Meynell argued that Orchardson’s ‘mission seems to be principally to teach repose … Mr Orchardson [has] convinced the world that a torment of accessories does not make for the dignity or the right naturalness of art’.7Alice Meynell, ‘Our Living Artists. William Quiller Orchardson R.A.’, The Magazine of Art, vol. iv, 1881, pp. 280–1.

By whisking away his expansive carpet, placing only a smallish rug underneath the husband’s feet, and painting new parquetry tiles across most of the floor area, the artist has suddenly heightened his scene with the impression of sound. This argument is over. The wife has nothing further to say. Thanks to the new wooden floor, the husband’s anger is met with not with the soft silence of carpet, but the clicking sounds of his departing wife’s high heels and the defiant swish of her dress across the amplifying surface of the parquetry. As with Tennyson’s poetry, when coupled with the painting’s title these sounds presage the coming of a ferocious, all-engulfing storm. The addition of sound at once increases the wife’s triumph and intensifies her husband’s speechless defeat.

Ted Gott, Senior Curator, International Art, National Gallery of Victoria