Article

Colonial anxiety repressed in strawberry tarts

BY Meitha Al Mazrooei

THEME LEADER National Gallery of Victoria

SUPPORTED BY University of Melbourne, as part of the NGV Triennial – exploring the emerging intersections of art, design, science and society.

Meitha Al Mazrooei’s agricultural investigation in the United Arab Emirates.

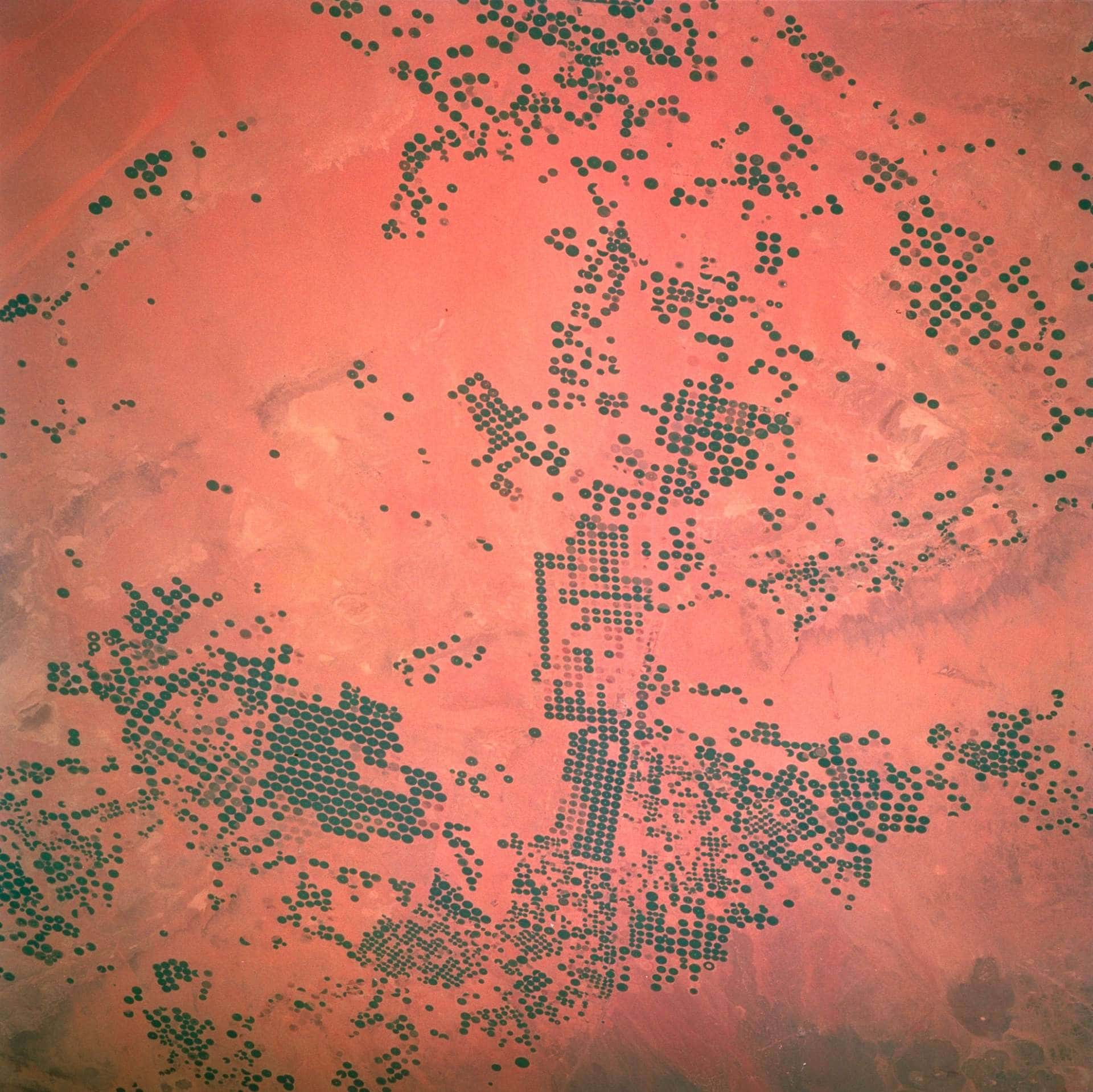

Ghantoot, UAE, Google Earth, October 2 2016

Flour, fat, water and salt. Four ingredients used to form a paper-thin circle that is 0.3 metres in diameter. A sandy surface waiting to be shaped, filled and stuffed to the brim with a set ingredient. An ingredient that is destined to be judged. Its producer, articulating an imagined identity through a flavour. Its receiver, oblivious to the social stigma attached to a savoury filling versus a sweet, delicate and potent herb.

The circle, awaiting an adequate amount of warmth, to be consumed.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, this notion that a society’s cultural productions served as reliable index of its moral character had become widespread and frequently used to give shape both to narratives of triumphant progress as well as to those of decadence and decline. This assumption is implicit in Lady Morgan’s contrast between the violent, cruel, raw flesh-eating barbarians and the humane, temperate, tasteful and refined Rothschilds.1

Although this simplifies the connection between a specific type of produce, flavour and dish and social status, food continues to be the fastest consumable way of adopting or disregarding a culture. It is used to extend the notion of participation and build a specific lifestyle, one of an articulated taste. A simple pie becomes charged with meaning and social implications. A nation’s, group’s and individual’s status is dependent on the choice between savoury and sweet. Taste is a measure of how far a community has evolved from ‘commoners’ to ‘elitists’.

West of Jeddah and south of Dubai, non-renewable fossil water is mined from a depth of 1000 metres and pumped to the surface. It is distributed via large centre-pivot irrigation feeds, to quench clusters of green circular patches.2 Formed on the large expanses of pale brown particles, the circular agricultural fields are 3000 metres in diameter and produce an array of fruits and vegetables that are exported to international markets and (partially) consumed locally.

When Westerners arrived in the Arabian Desert it was (naturally) perceived as barren, dry and unnatural relative to green, arable Europe. The only conceivable way to control the desert was to plant it. The colonial methodology remains part of the mindset of the Gulf States; it is a form of colonial anxiety that has prevailed long after the colonisers’ departure. The colonisers’ metaphysical presence is manifested in the Gulf’s constant urge to plant, irrigate and farm the large areas of empty land. The region perceives a (false) condition of desertification and the one attempt to reverse it comes in the form of capital investment in centre-pivot irrigation, camouflaged under the pretext of diversifying the economy and sustaining a growing population.

Most strategies aim to ‘green the desert’, ideas that are supported by the statement that desertification is a threat that affects 13 million square kilometres of the world’s land. In the current situation, in which the agencies, including the World Bank, funding these projects shield their ambitions behind the principles of ecology, their motivations are any different than those of the colonial foresters who planted trees as investment.3

Agricultural prosperity lies in the design of ‘gun sprinklers’. Patented by Frank Zybach in 1949, the Zybach Self-Propelled Sprinkling Irrigating Apparatus revolutionised farming in the United States, and the model was imported and implemented by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and United Arab Emirates (UAE) governments in 1993 and 2010 respectively.

The centre-pivot system comes with a detailed manual that specifies the pressure and which provides step-by-step guidelines for field calibration to avoid the accelerated wear of the sprinkler nozzle. The system aids in watering the diameter of the crop field in a uniform manner. This irrigation method is claimed to be beneficial in areas with high humidity, as the timed water application process can reduce evaporative losses,remaking the image and function of the terrain one rotation at a time.4

International Space Station imagery, agricultural fields, Wadi as-Sirhan Basin, Saudi Arabia 2012. Photo: NASA public domain

The current crop fields in Saudi Arabia span sixteen million acres of the desert and are dependent on desalination plants and local reservoirs. The circular green patterns follow the buried ancient river channels, where water is extracted from the wells and pumped to the surface. Desalination plants have helped with the supply of fresh water, but the production can’t keep up with the pace and density needed for the vast expanse.

The governments of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States have been actively investing in alternatives to fossil fuels. Agriculture production has been at the forefront of their attempts to diversify their economies. These nation states are heavily reliant on foreign imports, with 70 to 90 per cent of the available produce shipped into the country and consumed by the local population. This appears to be a sound investment in self-sufficiency. However, the Kingdom’s desert landscape is unfit for agriculture due to depleting water bodies, rendering the centre-pivot irrigation expenses a temporary fix for a larger climatic and economic issue.

The circles of green irrigated vegetation comprise a variety of agricultural commodities; the largest percentage of these is wheat. Bread and rice are staples of the Saudi diet. Wheat is a key ingredient in dishes, and the government has intended to align supply with the population’s demand/consumption. As a result of the integrated system, wheat production increased to a million tons in 1997, surpassing the quantity needed for domestic consumption twofold, and meanwhile costing the government eight times world prices (to grow wheat) and 80 per cent of its fresh water. Four slices of organic bread, toasted or not, in Saudi Arabia would take 400 litres of water to produce. The cost of supporting local ‘organic’ produce comes at a high price for the self-proclaimed climate aficionados.

The costs, it seems, could be covered in other ways within the agriculture network. The KSA’s Alkhorayef Group is one of the key players in the supply of centre-pivot irrigation systems, rivalling/aiding partners in China and the United States by supporting the manufacturing, distribution and production of the technology. The agency is responsible for building, distributing and maintaining the infrastructure for the government of Saudi Arabia. Alkhorayef Group is also the local supplier of water and power technologies, well-drilling, oil-contracting and both onshore and offshore draining systems. The business claims to run each sector as a separate subsidiary under the mother company, with each subsidiary independent with regard to resources and administration.

Meanwhile, in the UAE the adoption of centre-pivot irrigation is multifaceted. The large fields have been developed by Elite Agro, which is run as an independent business unit, although it is heavily subsided by the UAE government, and grows a range of produce for both sustenance and pleasure. The business exports vegetables and fruits ranging from eggplants to figs, with a large percentage of the crop fields dedicated to growing strawberries. This is possibly because they are considered refined, and because they add a familiar sweet flavour to any dish. Or, Elite Agro’s management is aware of the mythical connotations of the luscious fruit; allegedly, it has the ability to sustain growth on infertile lands, which renders the company’s tagline, ‘Let deserts bloom!’, an imaginable condition.

The strawberry fields are not, in reality, lighthearted. Their presence calls for high-level security, equivalent to that in place at military camps in the UAE. The expanse of land in Ghantoot (an area between Abu Dhabi and Dubai) is gated, and encircled by surveillance cameras and barbed wire. Individuals passing through the gates to the capitalist green havens require passes granted by the keepers. (Are these undefined keepers, government agents or Elite Group management?) The fields are situated adjacent to the equally highly secured fence that runs 34 kilometres between the capital and its neighbour, and which encloses the sanctioned natural reserve that houses water pools, endangered animals and military guard towers. Its gates, however, are not marked by the image of a luscious fruit, but with a sign labelling the expanse ‘غابة صباح الخير’, or the Good Morning Forest.

In addition to supplying regional markets with produce, Elite Group provides consultancy services and management. Tailored to each client’s needs, a proposal is shared regarding farm development, irrigation methods and post-harvest strategies, as well as purchasing and disseminating farming infrastructure to develop arable and infertile lands. This situates Elite Group as the main body able to provide clear methods of practice, from a conceptual starting point to a packaged berry, for an undisclosed fee.

The agriculture group is exporting its knowledge to the fields of Serbia and Morocco through implementing its found research from the UAE labs. In March 2013 Elite Group announced plans to purchase eight farming companies in Serbia. The agreement was solidified in July 2014 by the Serbian government, whereupon it entered into a joint venture with the organisation that entailed the acquisition of two state farms in Serbia.5

Other food ventures include privatised institutions and investors such as Al Qudra Holding and Al Dahra Agriculture Company. In June 2008 the investors were given more than 70,000 acres of farmland in Sudan, on the condition that they would invest in the land.6 The plans included harvesting corn, alfalfa, wheat, potatoes, beans and strawberries.7

The details of the agreements are validated by claims from the participants in the exchange: the initiatives help to provide jobs and economic security for the host state where their own governments failed to do so – and on lands that are unused or not used to their full potential. Most agreements come with a time frame. However, the impact on the indigenous populations that have cultivated the lands for generations is great. The pace of the highly technologised agricultural process surpasses the land’s resources, depleting the nitrogen at an exponential rate, often before the deal’s expired date. This leaves the previous owners and farmers with non-arable lands.

Nevertheless, these foreign agricultural land acquisitions have not been as successful as predicted. Many such projects have shown limited returns; barelyone in five (land activation) has resulted in actual farming.8

There are a number of reasons for the failure to reach projected investment returns. The countries involved have failed to reach a conclusion with regard to which side is responsible for the risks that surface (both political and weather related). The World Trade Organization’s legislation also impacted the deals, as it restricts food exportation in times of shortage. As a result, the investing countries do not receive the produce. In 2014 Elite Agro joined with GLOBALG.A.P, a Europe-based ‘consultancy’ that manages the distribution of produce in selected European countries. It provides certified accreditation to its members, a stamp that is required in order to supply fruit, vegetables and grains in Europe. Currently, the UAE is the only Middle Eastern country with access to the network, and along with Thailand, it is one of only two non-European countries to hold membership. The strawberries from Ghantoot are then packed, stamped and shipped through this controlled supply chain, in a form of food diplomacy that’s light, pigmented and delectable.

A representative from Modern Bakery in Dubai, a private business that supplies all coffee franchises in the country with baked products, stated that all their registered outlets in the UAE have strawberry tarts on their menu. This means a supply of approximately 4500 tarts to Starbucks alone. However, clarity with regard to the source of the strawberries varies. The tarts supplied to organic cafes in the country use strawberries from regional farms, without specifying the preferred farm and plot location. The tarts baked for the remaining listed cafes contain strawberries imported from the United States, which begs the question of where the strawberries from Elite are ending up. Are they all exported through GLOBALG.A.P? Are Elite Group’s audience in Europe consuming strawberry-infused desserts from strawberries harvested in their former colonies, reclaiming the right to the tart, to the land, in the sweetest form of political diplomacy?

But even circles are forced to evolve in order to conform to capitalist societies and their motives where technologies are developed and deployed to further exploit areas of land. Zaybach’s nozzle proved to be insufficient, creating dead spaces between the adjacent circles. In an attempt to make use of the non-arable areas formed between the circles, a new nozzle had to be designed in order to form hexagonal fields, reducing the non-arable area to zero per cent. Capitalist dreams cannot be engulfed within a circle, it seems. The round figure’s equidistant point from the centre produces wastage when the circles are multiplied. The negative triangular space between the radial crop fields is left infertile, reducing the possible profit margin by 30 per cent.9

As a method of minimising un-sprinkled areas, a few countries in the Middle East and North Africa (Libya) are arranging their agricultural fields in hexagonal patterns. Zybach’s nozzle has been adapted by amending the pressure consistency in order to resolve the issue. Through the installation of a sensor at the end of the pivot arm and radio signal wires within the corners of the field, the pipe is able to react to the signal and increases the pressure at the corners, eliminating the void and forming imagined layers of hexagonal landscapes, perceived by birds and travellers.10

‘The globalized food system is and always has been rooted in an ecological imperialism that protects some and leaves others painfully exposed’, Fabio Parasecoli has written.11 Imperialism is taking on different structures and tastes, where Di Palma’s commoners’ savoury pie evolves to accommodate imperialist tastes, and the formal patterns of crop fields evolve as a response to imperial economic aspirations. Will the hexagonal strawberry tart become the new symbol, masking the intentions of new colonisers, the preliminary layer of a new sandy crust, waiting to be consumed?

Arabian Desert, Nasa, December 2 2012

Meitha Al Mazrooei is the founder and editor of WATAD architecture and design magazine. She is currently pursuing a Masters of Science in Critical, Curatorial and Conceptual Practices in Architecture at Columbia University.

References

1. Vittoria Di Palma, ‘Empire gastronomy’, AA Files, no. 68, 2014.

2. Miguel Quemada & Jose L. Gabriel, ‘Approaches for increasing nitrogen and water use efficiency simultaneously’, Global Food Security, vol. 9, June 2016, pp. 29–35.

3. Rosetta S. Elkin, ‘Desertification and the rise of defense ecology’, Portal 9, no. 4, Autumn 2014.

4. Shabbir A. Shahid & Mushtaque Ahmad, Environmental Cost and Face of Agriculture in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: Fostering Agriculture in the Context of Climate Change, Springer, Cham, 2014.

5. Sanaa Pirani & Hassan Arafat, ‘Interplay of food security, agriculture and tourism within GCC countries’, Global Food Security, vol. 9, 2016, pp. 1–9.

6. ibid.

7. Marie Claire Custodio, Matty Demont, Alice Laborte & Jhoanne Ynion, ‘Improving food security in Asia through consumer-focused rice breeding’, Global Food Security, vol. 9, 2016, pp. 19–28.

8. Sanaa Pirani & Hassan Arafat, ‘Interplay of food security, agriculture and tourism within GCC countries’, pp. 1–9.

9. Miguel Quemada & Jose L. Gabriel, ‘Approaches for increasing nitrogen

and water use efficiency simultaneously’, pp. 29–35.

10. Randy Alfred, ‘July 22, 1952: genuine crop-circle maker patented’, Wired, 22 July 2008.

11. Fabio Parasecoli, ‘Taste of Empire’, Tank Magazine, no. 68, 2016.