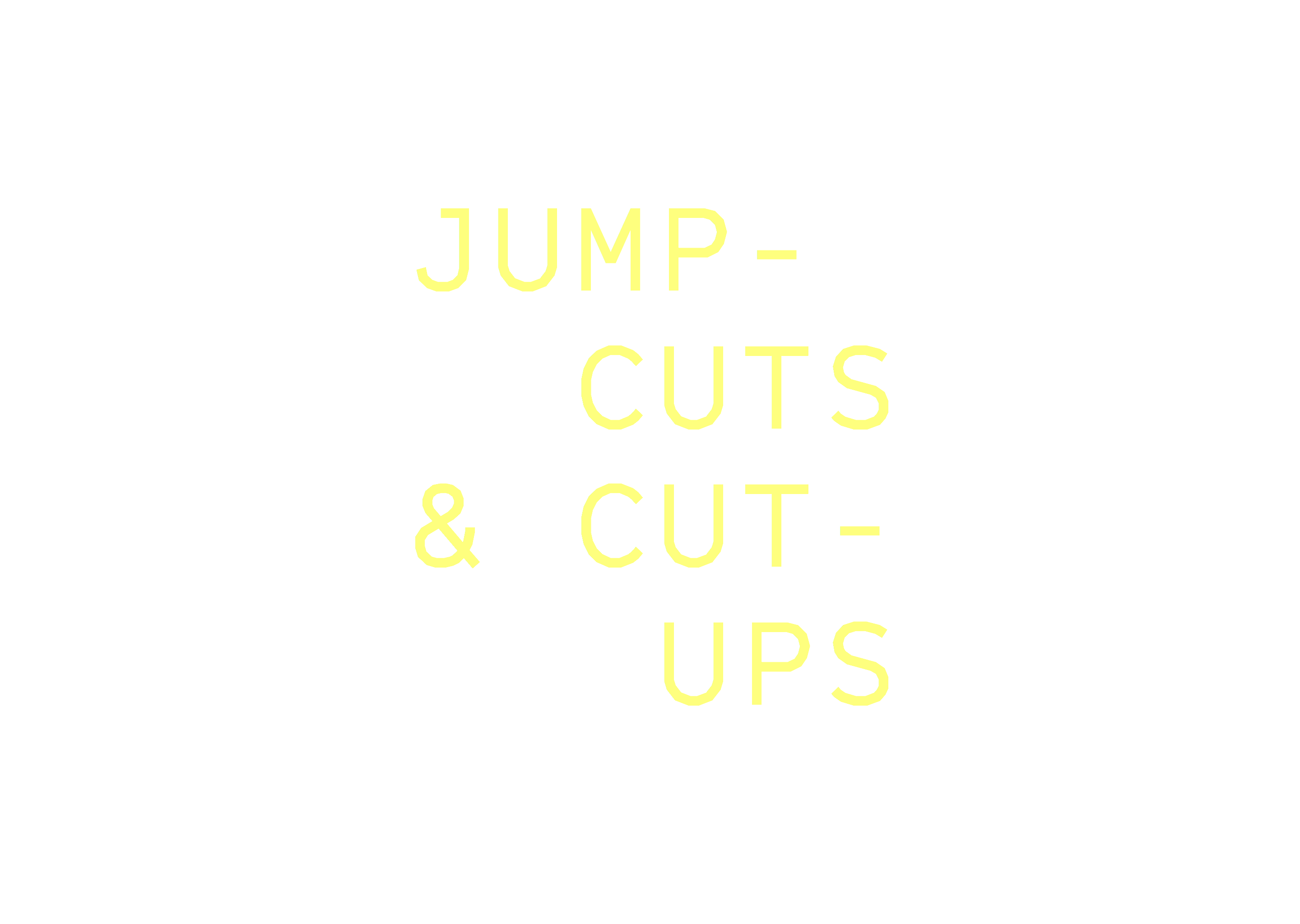

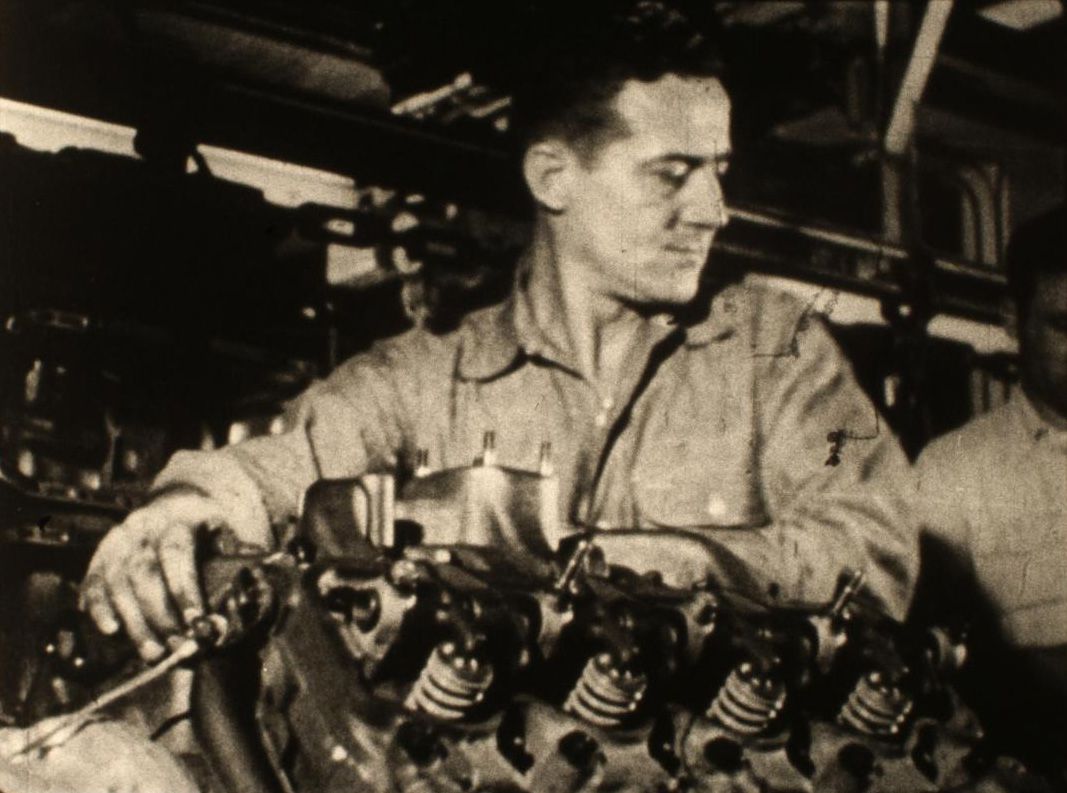

Len Lye was a pioneer of the jump-cut technique in commercial television. Rhythm, 1957, the earliest work included in Transmission, is a brilliant example of this manual editing technique used to dynamic effect. Lye used his knowledge of producing experimental and documentary films to create the short film, which was intended originally for television broadcast for the Chrysler Corporation’s weekly television program in the United States. The artist’s biographer, Roger Horrocks, has described how Lye was commissioned by James Manilla, an advertising executive of McCann-Erickson, to come up with an idea for ‘an experimental something’ between one and two minutes long. Manilla assisted Lye in obtaining more than one hour’s worth of black-and-white documentary footage of an in-house film shot for Chrysler of the making of a car from start to finish (including the offcuts). In a radical move for the time, Lye then manually cut together scenes he described as having ‘a good, definite, contrasty quality’ using dramatic jump cuts, so that the assembly of the car appeared sped up.1 The spliced footage was overlaid with a soundtrack of traditional African tribal drumming and chanting, creating an extraordinary syncopation between the footage and music, content and effect. Filmmaker and writer Brett Kashmere has noted Lye’s political interests in working conditions and the racial issues of the day: ‘Signalling Lye’s blue-collar background and another subtle sign of his attendance to racial issues, the film includes and abbreviates the image of a winking African-American factory worker’.2 Lye himself is quoted as having attempted to ‘kinetically convey the vitality and romanticism of efficient workers in their everyday jobs’.3 The short film received the New York Art Directors’ Festival First Prize for the year’s best television commercial in 1957 but, interestingly, was later disqualified due to the fact the Chrysler Corporation had never actually broadcast it on television. As Horrocks has written, the corporation was troubled by the shot of the black worker winking at the camera and the use of African tribal music, ‘which seemed out of keeping with the serious business of making Chrysler cars’.4

There is an opacity to the found material, an insistent but mute materiality: limb-dislocating contortions, foetus-pale flesh, eyes vacant in trance or stiletto-sharp with vigilant pride, maniacal smiles that split apart the dead grey mask of English ‘mustn’t grumble’ mundanity, faces disfigured with bliss.9

Artist Robert Rooney is highly connected to popular culture and his local environment. As the music scholar John Whiteoak has observed, Rooney

studied, and was genuinely intrigued by, seemingly banal, mass-produced objects from his immediate suburban environment; this, in turn, was tied to a strong awareness of the effect of mass production and mass media on society.10

Rooney once said, ‘I have always preferred to work from secondary sources, particularly mass-media ones, rather than paint or draw from the actual subject’, and television was a recurring and ubiquitous background presence for his work, as described in an artist statement from 1975:

PAINT:

The only time I enjoyed using paint was when I was putting on the white undercoat. The preparation was laborious – up to two weeks to prepare the canvas and a few hours to paint it.

I used to watch television while I painted.11

The work by Rooney featured in Transmission captured images on the TV set using Super-8 film, and excerpts from the footage were then manually cut up and looped together, creating a new, rhythmic collage that seems to exist in an eternal loop.

- Roger Horrocks, Len Lye: A Biography, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2002, p. 261.

- Brett Kashmere, ‘Len Lye’, May 2007, Senses of Cinema, <http://sensesofcinema.com/2007/great-directors/lye/>, accessed 20 April 2015.

- Horrocks, p. 261.

- ibid., p. 262.

- The Casuals have been described as ‘a subset of football hooligans who emerged in the 1970s when they began to wear instead of football colours expensive European designer clothing by the likes of Gucci, Burberry, Fiorucci, Lacoste, Jordache, Fila, Sergio Tacchini, Adidas and more. These designer labels and expensive sportswear were a way to deflect attention from the police and other clubs, making it easier to infiltrate rival clubs and get into bars. The luxury brands allowed them to subsume the identity originally connected to an upper class in order to carry on with their working-class behaviour. Some might say it is a contemporary form of the proletariat distracted by the lascivious culture handed them by Capital as they go round-and-round à la Debord in the arena they have made. They don’t care. And we don’t either as we fall into this video unable to pull away, our insatiable thirst only intensified as the minutes pass’ (Horrocks, pp. 24–5).

- James Voorhies, Seventh Dream of Teenage Heaven, Canzani Centre Gallery, Columbus College of Art and Design, Ohio, 2011, p. 23.

- As Sophie O’Brien has written, this editing and sourcing of video materials is particularly notable because at the time the ‘internet was comparatively new, and YouTube did not yet exist’ (Sophie O’Brien, Carolyn Kerr & Helen Little, Turner 08, Tate Publishing, London, 2008, p. 13).

- O’Brien, Kerr & Little, p. 13.

- Simon Reynolds, ‘They burn so bright whilst you can only wonder why: watching Fiorucci made me hardcore’, text for the Mark Leckey retrospective at Serpentine Gallery, London, 2001, RenoldsRetro, <http://reynoldsretro.blogspot.com.au/2012/06/normal-0-false-false-false-en-us-x-none.html>, accessed 20 April 2015. Following in the long history of music sampling, segments of the original dance footage continue to be reworked and reused, a recent example being the music video for DJ Shadow’s I Gotta Rock (Metal Madness Video), 2011.

- John Whiteoak, ‘Robert Rooney and the McKimm/Rooney/Clayton Music Collaboration: Melbourne, 1960s’, in Jenepher Duncan, From the Homefront: Robert Rooney Works 1953–1988, Monash University Gallery, Melbourne, 1990, p. 19.

- Robert Rooney, ‘Less than five hundred words in retrospect’, in Project 8: Robert Rooney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1975.