Rembrandt's watermarked papers at the National Gallery of Victoria

Introduction

The NGV holds 140 Rembrandt prints, a growing collection of the artist’s intaglio works first purchased in 1891 with a new acquisition as recent as 2023.1The first NGV acquisition of Rembrandt’s prints were eleven etchings purchased in 1891 from London; many more have been acquired via the Felton Bequest and recent acquisitions have been granted by the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program. In preparation for the exhibition Rembrandt: True to Life2Watermark ID and variants are published in the list of works (pp. 248–53) of the Rembrandt: True to Life catalogue. held in the winter of 2023 at NGV International, NGV paper conservators documented and studied this collection of prints not only to assess their condition and ensure their preservation, but to gain a deeper understanding of the artist’s printmaking materials and processes.3See ‘Rembrandt’s printmaking techniques’ by Louise Wilson and ‘Rembrandt’s papers’ by Ruth Shervington, in Rembrandt: True to Life, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, pp. 234–41. Over the last thirty years paper conservators have focused on capturing and studying the watermarks found in Rembrandt’s prints and this research is now available to the public in the form of this online database, Rembrandt’s Watermarked Papers at the National Gallery of Victoria. This database aligns with Watermarks in the NGV’s collection of prints by Albrecht Dürer,4This watermark database was published online 2016 and made possible with the generous support of Dr Susanne Pearce. comprising approximately 200 watermarks.

Background

Revered as a prolific and experimental printmaker, Rembrandt sourced and printed on a great variety of papers of both Western and Eastern5A survey of the NGV’s Rembrandt prints on Asian papers was compiled by Jacobus van Breda: Rembrandt etchings on Oriental papers. origin, and sometimes even on parchment (animal skin). Although Rembrandt printed primarily on white coloured paper, he experimented with other types of papers to achieve aesthetic variation among his impressions. For example, he printed on ‘oatmeal’ paper, so-called for its cream or grey colour and lumpy or textured appearance,6Within this collection of Rembrandt watermarks, paper conservators have captured an unknown fragment within oatmeal paper for the impression Jan Lutma, goldsmith, c. 1648 and Eastern papers (Japanese, Chinese and Indian papers) that offer a subtle shine and softness. He was also known to tint his papers before or after printing. Overall, it is believed that Rembrandt printed on a least 350 different kinds of paper.7Christopher White. 1999, Rembrandt as an Etcher: A Study of the Artist at Work (2nd ed.), Yale University Press, New Haven, pp. 8–11.

The Western papers from the period are distinctly made from linen and cotton rag fibre with a laid papermaking mould and wire profile, which creates the watermark. A wire profile is made, fashioned and shaped to form a symbol or pictorial design, and then is sewn to the laid wire mesh of a papermaking mould. As a sheet of paper is formed on the mould, the wire profile of the watermark leaves a subtle impression within the sheet, often only visible by manipulating light to view it. Watermarks have been found in Western handmade papers as early as the late 13th century8Watermarks depicting simple crosses and circles are used in Europe (likely Italian) from 1282. The fleur-de-lis watermark appears shortly after in 1285. Hunter 1978, p. 474. and are a method by which papermakers can mark or distinguish their product.

Figure 1: Example of an antique laid papermaking mould with an Acorn wire profile, made by Paper Mouldmaker Serge Pirard. This traditional papermaking mould was kindly purchased from the NGV’s Supporters of Conservation Projects fund and is part of the NGV’s Conservation Material Archive.

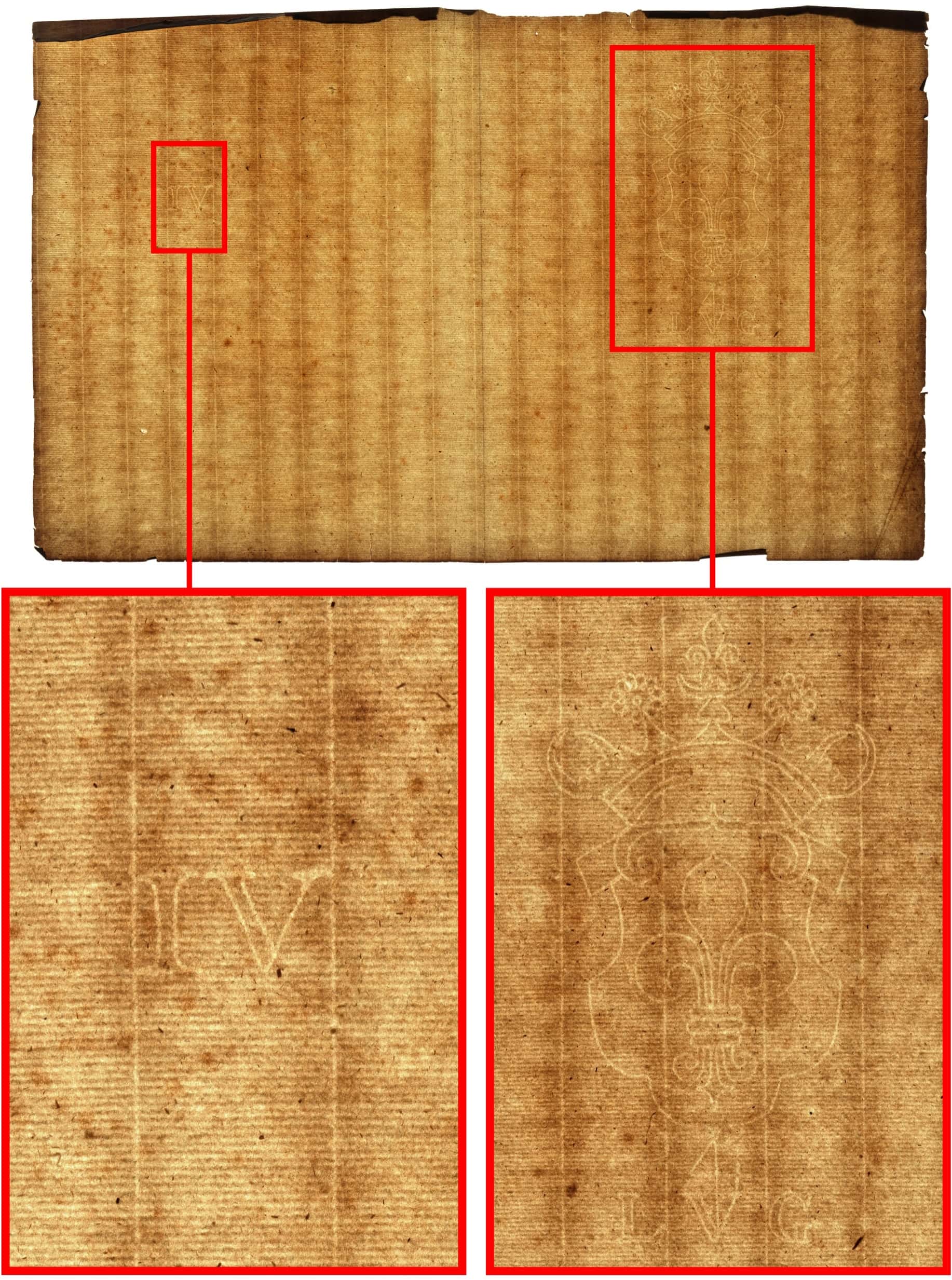

Shortly after the first watermarks appeared in Western papers, a secondary mark known as a countermark was developed. Countermarks are often smaller symbols or letters that signify a papermaker’s monogram, a papermaking mill, a place name, or a patron’s name. Countermarks are fashioned in the same manner as a wire profile and the two are traditionally sewn on either side of the papermaking mould.

Figure 2: Example of a full sheet of antique laid paper with the Strasbourg lily watermark on the right and initials IV countermark on the left. This sheet is from the Album of watermarks (compiled in 19th century) by Canon von Büllingen.

Centuries later, paper conservators, historians and curators have studied the elusive watermarks and countermarks left by European papermakers. Watermarks are hidden clues with the potential to reveal or suggest the origin of a single sheet of paper. They can signify where a sheet was made (and in some instances by whom), provide insight into paper production, economy and paper trade at the time, while conveying a sense of how individual artists, such as Rembrandt, used or favoured certain papers throughout his printmaking practice.

Documenting watermarks

Traditionally watermarks have been studied using a source of transmitted light (such as a candle or natural light) shone from behind the sheet, revealing the thinner and more translucent areas in the paper caused by the watermark. Watermarks were often traced with ink and pencil: sometimes onto a separate sheet, and sometimes directly onto the watermark.9The Album of watermarks (compiled in the 19th century) by Canon von Büllingen has many examples of traced watermarks. Further information about the album can be found in the article by Louise Wilson, ‘Bibliomania; or book madness: the story of the von Büllingen album of watermarks’, published in The Quarterly, the Journal of the British Association of Paper Historians, no. 120, Oct. 2021, pp. 1-11. Another early method was to make a rubbing impression of the watermark. This was done by placing a thin sheet of paper over the watermark, and lightly rubbing with a friable medium, such as chalk, crayon or graphite to take a tracing.

As technology has advanced, paper conservators have utilised various imaging techniques to record and document watermarks and paper structure. These include beta-radiography, transmitted light imaging and raking light imaging.

Figure 3: Rembrandt’s etching, Self-portrait (?) with plumed cap and lowered sabre, 1634, National Gallery of Victoria, is animated to show a reflected light image, a transmitted light image, and a beta-radiograph image.

At the NGV, paper conservators have been using beta-radiography since the early 1990s. Beta-radiography is an x-ray imaging technique using a radioactive plate10The NGV use a beta-plate which is a 1mm thick sheet of acrylic (polymethacrylate) containing radioactive Carbon-14, approximately 17 x 12 cm in size. that emits low energy beta-particles that pass through the paper, capturing its internal structure as an image on x-ray film. The process involves placing the work on paper between a radioactive plate11Beta-radiography is a non-destructive analytical technique that is not considered harmful to conservators or artwork due to its low energy emitting beta-particles and limited contact time. and a sheet of x-ray photosensitive film. To create even yet gentle contact between the three materials, a sheet of mount board, glass and weights are placed on top.

Figure 4: Diagram of beta-radiograph stack used for capturing watermarks.

Depending on the thickness of the paper, exposure times can vary to capture a clear and quality image.12Exposure times used for beta-radiography of Rembrandt watermarks vary from 0.75 hours to 5 hours. The exposure time is calculated by the weight of each individual sheet. NGV paper conservators currently use x-ray film that is developed with chemicals, much like developing photographic negatives in a darkroom. After processing, the film reveals the internal structure of the paper, such as chain and laid lines, paper density, pulp distribution and watermarks when present. Beta-radiography is especially useful in examining the paper of heavily inked prints, such as Rembrandt’s Christ crucified between the two thieves (The Three Crosses), 1653-1655, National Gallery of Victoria, where there is little paper reserve visible13Media containing heavy inorganic pigment such as lead can block beta-particles and impede capture of paper structure using beta-radiography. .

Figure 5: Rembrandt’s, Christ crucified between the two thieves: (The Three Crosses), 1653-1655, National Gallery of Victoria, with overlay of Strasbourg bend watermark on the right side.

When a work is photographed using transmitted light, the image captures the colour of the paper, its fibres, the transparency of the sheet and appearance of media. Raking light imaging involves light shone at a low angle, which rakes across the surface of the paper so that highlights and shadows appear, detailing the surface topography and capturing the delicate impression of the watermark. Raking light can reveal the ‘wire side’14See definition of ‘wire side’ below. of the sheet.

Database of Rembrandt’s watermarked papers

This database presents fifty-eight individual watermarks, both complete and fragments from eighteen watermark design groups. Many of the watermarks shown here were included in Erik Hinterding’s 2006 catalogue of watermarks, Rembrandt as an Etcher. This catalogue is the most comprehensive study of watermarks within Rembrandt prints and has been the primary reference used for the NGV’s collection of watermarks. Variant descriptions and coding systems for watermarks in this database align with Hinterding’s catalogue. Additionally, watermark IDs have been published alongside the list of works in the exhibition catalogue Rembrandt: True to Life15Kayser, 2023, pp.248-53..

For each watermark captured, conservators have presented:

Watermark form – The design group or category which the watermark falls into. Note that watermark nomenclature can vary.16For example, the watermark Arms of Ravensburg is also known as the Two Towers. This watermark design is a version of the cities coat of arms during the period and visually depicts a shield with two towers above a city gate.

Watermark and variant description – An alphabetised coding system to describe the variant (capital letter) and sub-variant (lowercase letter) of the watermark form17Hinterding’s coding system is built on Nancy Ash and Shelley Fletcher’s 1998 catalogue Watermarks in Rembrandt’s Prints. . Lowercase letters a.a and a.b differentiate watermarks made on the same mould or twin moulds18Papermakers used two moulds in rotation during the papermaking process, the pair are known as ‘twin moulds’. Watermarks that appear identical are likely made from the same papermaking mould while watermarks that appear nearly identical are likely a twin watermark, made from the second mould. and the letters z.z indicate the sub-variant cannot be identified. Followed by a visual description of the watermark.

References – A range of watermark catalogues and manuals have been referenced to identify watermark forms and variants, where possible. A full list of references used in this study are listed below.

Completeness – The database shows twenty-six watermarks in their complete form while thirty-two are only partial watermarks. Rembrandt used a variety of different sized copperplates that required various sizes of paper for printing. The artist would have likely cut his paper from larger sheets into smaller formats shown below, which is why only fragmentary watermarks are often present. Furthermore, it was not uncommon for collectors of fine art prints to trim their treasured works as they assembled these into albums.19See the NGV’s Album of portrait engravings (Collins album) compiled of many trimmed prints.

Figure 6: Diagram of the various copper plate and sheet sizes used by Rembrandt.20Based on Hinterding’s diagram, fig. 8, p. 28.

Chain line interval – The distance between chain lines measured in millimetres.

Laid line frequency – The number of laid lines per centimetre.

Placement and spacing of wires – A standard physical measuring system21This system was developed by filigranologist Allan Stevenson. has been adopted by many in the field, as a way of comparing similar or closely related watermarks. This system considers the following measurements in millimetres:

a = Height of watermark

b = Distance from the chain line left of the watermark and left edge of watermark

c = Distance from left edge of watermark to bisecting chain line (indicated by the stroke|)

d = Distance between two chain lines bisecting watermark (indicated by second stroke|, if applicable)

e = Distance from last bisecting chain line to right edge of watermark

f = Distance from the right edge of watermark to chain line right of watermark

*Note the sum of numbers in brackets [c-e] should equal the total width of watermark*

? = When the measurement cannot be determined (because the watermark is partial or cannot be seen clearly)

For example, the fleur-de-lis watermark from Rembrandt’s print the Death of the Virgin, 1639, National Gallery of Victoria, is measured: 64 x 21 [7|30|7] x 22 mm

Figure 7: Diagram showing how the placement and spacing of wires is measured for a Fleur-de-lis watermark.

Wire side – The side of the sheet that was in contact with the wire profile of the papermaking mould during manufacture. Recto is the front or the printed side of the sheet, and verso is the back of the sheet. For some prints it is not possible to determine if the wire side is the recto or verso.

Radiography taken from – In general, the beta-radiograph in the database were taken from the recto of the work of art. However, digital beta-radiographs shown here have been manipulated to reflect the orientation of the watermark as it likely would have appeared on the papermaking mould, determined by the wire side of the sheet.

Watermarks found in Rembrandt’s prints

During Rembrandt’s working life, papers were imported to the Netherlands from nearby countries and regions22Papermills were not well established within the Dutch Republic until after 1685 and during Rembrandt’s working life paper was imported to the Netherlands from Germany, Switzerland and France. Hinterding, 2006, pp. 42–7. and the watermarks of these papers give us clues to their origin. Many watermarks in this collection show the coat of arms of a city or region or can be connected to a place of origin by a mere motif.

For example, papers likely imported from Germany are those with the Arms of Württemberg and Arms of Ravensburg watermarks, depicting heraldry of these historical German territories. While the Foolscap watermark likely originated in Germany, the motif was also used by neighbouring countries France and Switzerland.

French papers within the Collection show the Strasbourg bend, also known as the Arms of Strasbourg, signifying the city in Eastern France. Papermakers from Strasbourg also commonly used the Strasbourg lily watermark, and both these watermarks often appear with the monogram ‘WR’, the papermill of Wendelin Richel (or Rihel) operating from the 16th century. The Fleur-de-lis watermark likely originates in France but was also a motif found in early Italian papers and later used by German papermakers. While the Cross of Lorraine watermark, with intertwining letter Cs, references Charles III and his wife Claude, Duke and Duchess of Lorraine.

The Basel Crozier symbol, which depicts the crook of the Bishop of Basel’s staff, is a watermark motif found in papers produced in Switzerland. In Rembrandt’s papers this symbol is found below the beak of the Basilisk watermark and on the shield of the Eagle, double-headed watermark. Both watermarks are connected to the Heusler papermaking family in Basel.

Although papers were not manufactured in the Netherlands during Rembrandt’s working life, papers were being produced specifically for the Dutch market. This is evidenced by the Arms of Amsterdam watermark, the city’s coat of arms, and the Seven provinces watermark, which shows a rampant lion holding seven arrows to symbolise the Dutch republic. Both watermarks are likely made in France and commissioned by the Dutch capital.

In the NGV’s collection of Rembrandt prints, four of the fifty-eight watermarks are countermarks in the form of initials. As previously mentioned, countermarks can connect a sheet of paper to specific papermaking mill or patron. For example, the Countermark LB23The initials LB are also seen in the Arms of Württemberg watermark, below the shield, within the paper of Rembrandts print Bearded man in a furred oriental cap and robe: the artist’s father at NGV. Also, Hinterding has connected the countermark LB to the Foolscap with five-pointed collar watermark. possibly relates to Léonard Binninger of Montbéliard, a patron of the Belchamp papermaking mill operating along the Doubs River in Eastern France between 1613 and 164324Léonard and Jean Binninger are associated with the Belchamp papermaking mill during its later operating years from 1632 to 1643. Guatheir, 1897, p. 27. .

Watermark catalogue references

The following watermark catalogues are cited in the online database.25This list combines catalogues cited by NGV paper conservators and referenced by Hinterding in the 2006 catalogue.

Nancy Ash, Shelley Fletcher and J. P. Filedt Kok, Watermarks in Rembrandt’s Prints, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1998.

C. M. Briquet and Allan Stevenson, Les Filigranes. Dictionnaire Historique Des Marques Du Papier Dès Leur Apparition Vers 1282 Jusqu’en 1600 [Par], Paper Publications Society, Amsterdam, 1968.

W. A. Churchill, Watermarks in Paper in Holland England France etc. in the Xvii and Xviii centuries and Their Interconnection, M. Hertzberger, Amsterdam, 1935.

Georg Eineder and E. J. Labarre, The Ancient Paper-Mills of the Former Austro-Hungarian Empire and Their Watermarks, Paper Publications Society, Hilversum, Holland, 1960.

Raymond Gaudriaud, Filigranes et autres caractéristiques des papiers fabriqués en France aux XVIIe et XVIIe siècles, CNRS, Paris, 1995.

Jules Gauthier, L’industrie Du Papier Dans Les Hautes Vallées Franc-Comtoises Du Xve Au Xviiie Siècle, Par Jules Gauthier,. Montbéliard: Impr. De V. Barbier, Montbéliard, 1897.

Edward Heawood, Watermarks Mainly of the 17. And 18. Centuries, Paper Publications Society, Amsterdam, 1969.

Erik Hinterding and Nancy Ash, Rembrandt as an Etcher. Studies in Prints and Printmaking, V. 6, Sound & Vision, The Netherlands, 2006.

N. P. Likhachev,P J. S. G Simmons and B. J. van Ginneken-van de Kasteele, Likhachev’s Watermarks : An English-Language Version, Paper Publications Society, Amsterdam, 1994.

Frits Lugt, Wandelingen Met Rembrandt in En Om Amsterdam 2. Vermeerderde druk ed. P.N. van Kampen, Amsterdam, 1915.

Joseph Meder, Dürer-Katalog : Ein Handbuch Über Albrecht Dürer’s Stiche Radierungen Holzschnitte Deren Zustände Ausgaben Und Wasserzeichen., Gilhofer & Ranschburg, Wien, 1932.

Alexandre Nicolaï, Histoire Des Moulins À Papier Du Sud-Ouest De La France 1300–-1800; Périgord Agenais Angoumois Soule Béarn, G. Delmas, Bordeau, 1935.

Paper Publications Society, The Nostitz Papers: Notes on Watermarks Found in the German Imperial Archives of the 17th & 18th Centuries and Essays Showing the Evolution of a Number of Watermarks. : Paper Publications Society, Hilversum Holland, 1956.

Tromonin Kornilīĭ Tromonin, S. A. Klepikov and J. S. G. Simmons, Tromonin’s Watermark Album : A Facsimile of the Moscow 1844 Edition: With Additional Materials by S.a. Klepikov, Paper Publications Society, Hilversum Holland, 1965.

W. Fr. Tschudin and E. J Labarre, The Ancient Paper-Mills of Basle and Their Marks, Paper Publications Society, Hilversum Holland, 1958.

Henk Voorn, Stichting voor het onderzoek van de geschiedenis der Nederlandse papierindustrie (Haarlem). Haarlem, De Papierwereld 1960

Friedrich Wibiral, L’iconographie D’antoine Van Dyck D’après Les Recherches De H. Weber, A. Danz., Leipzig, 1877.

Lucien Wiener, Étude Sur Les Filigranes Des Papiers Lorrains, Nancy, R. Wiener, 1893.

Other references

Dard Hunter, Papermaking : The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, (2nd ed.), rev Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1967.

Petra Kayser, Rembrandt: True to Life, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2023.

E. J. Labarre, Dictionary and Encyclopaedia of Paper and Paper-Making, (2nd ed). Swets & Zeitlinger, Amsterdam, 1952.

E. G. Loeber, Paper Mould and Mouldmaker. Amsterdam: Paper Publications, Amsterdam, 1982.

Christopher White, Rembrandt as an Etcher : A Study of the Artist at Work, (2nd ed.) Yale University Press, New Haven, 1999.

Watermarks in the NGV’s Collection of prints by Albrecht Dürer

Louise Wilson, ‘Bibliomania; or book madness: the story of the von Büllingen album of watermarks’ in The Quarterly, Journal of the British Association of Paper Historians, no. 120, Oct. 2021, pp. 1-11.

Acknowledgements

Watermarks for this database have been gathered and studied over many years by paper conservators: Lyndsay Knowles, Cobus van Breda, Ruth Shervington, Louise Wilson and Yvonne (Bonnie) Hearn. With contributions from curators: Irena Zdanowicz, Cathy Leahy and Petra Kayser and researchers abroad: Emanuel Wenger, Frieder Schmidt and Peter Bower. Thanks to the NGV Multimedia team who assisted in compiling the research online: Jenny Walker, Jonathan Luker, Madi Reader and Oscar Jackson and a special thanks to conservator Manon Mikolaitis for project assistance. The NGV is extremely grateful for the work of Erik Hinterding and his assessment of the watermarks within the Rembrandt prints at the NGV included in the 2006 catalogue Rembrandt as an Etcher, Studies in Prints and Printmaking, and also Andrew C. Weislogel and C. Richard Johnson, Jr who have advanced Hinterding’s study via the Watermark Identification in Rembrandt’s Etchings (WIRE) project. Lastly, a special thanks to Andy who kindly assisted in identifying recently captured NGV watermarks.

Arms of Amsterdam

Arms of Amsterdam

Arms of Ravensburg

Arms of Ravensburg

Arms of Württemberg

Arms of Württemberg

Basilisk

Basilisk

Countermark JB

Countermark JB

Countermark LB

Countermark LB

Countermark PB

Countermark PB

Countermark WK

Countermark WK

Cross of Lorrain

Cross of Lorrain

Eagle, double-headed

Eagle, double-headed

Fleur de lis

Fleur de lis

Foolscap fragment

Foolscap fragment

Foolscap with five-pointed collar

Foolscap with five-pointed collar

Foolscap with seven-pointed collar

Foolscap with seven-pointed collar

Grapes

Grapes

Horse and rider

Horse and rider

Miscellaneous, late

Miscellaneous, late

Serpent

Serpent

Seven provinces

Seven provinces

Strasbourg bend

Strasbourg bend

Strasbourg lily

Strasbourg lily

Unknown fragment

Unknown fragment  Unknown fragment, partial crown

Unknown fragment, partial crown